Lundy Island provides an annual place of pilgrimage for STEVE DOVER, friends and children – and more often than not the seals are up for a laugh.

WE WERE BEING BLOWN out by 55mph winds from the west and, dramatic as this can be on the north Devon coast, it is not conducive to diving.

Add in that the tide would have been ebbing swiftly when we would be halfway from Clovelly to Lundy Island – creating the kind of maelstrom that Captain Ahab would avoid even if Moby Dick was waving a white flag – and you’ll understand why I called off the dive.

With British weather, there are no guarantees. And Clive Pearson – owner and skipper of our charter-boat Jessica Hettie – was the first to remind me of this when I booked.

He has been doing that consistently since I first booked him to take us to Lundy in 1992.

Clive’s other consistencies are meticulous attention to detail, an intimate knowledge of the north Devon coastline and the Bristol Channel tidal and weather systems, and his on-board culinary skills.

But this July the weather forecast was for light westerlies. I had chosen July because on a previous trip we had happened across seven or eight basking sharks trawling plankton halfway to the island.

The experience of snorkelling with these vegetarian leviathans was one of those special underwater moments, and I hoped to be lucky enough to repeat it.

We arrived in Clovelly on Friday evening. The village must be one of the most picturesque and unique in Devon and Cornwall.

It is clustered up a steep and narrow cobbled street starting in the woodland above and ending at the harbour wall hundreds of feet below.

There is no access for cars. Dave didn’t know this when he left his wallet behind. By the time he returned, panting heavily but triumphantly waggling his wallet, we had downed two pints.

Breakfast in the New Inn on Saturday morning was excellent. My son Fiohann enjoyed kippers. I had advised dry toast and bacon, but frankly I wouldn’t have listened either if I was 15.

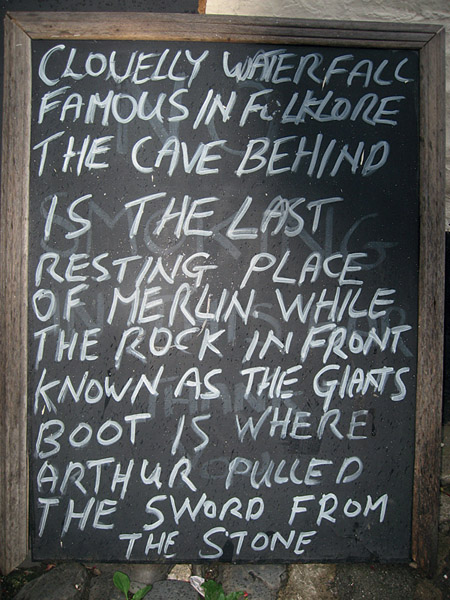

We explored the village and saw the “famous” waterfall – well, it’s famous on days when the villagers know that American tourists are in town.

At 11 we loaded the boat, including manhauling Andris’s twin-12s down the ancient steps.

Clive frowned at the sight of the heavy twin-set, knowing that if it fell over onto someone’s foot it would do permanent damage.

But soon we were looking back at the dwindling village as the boat dipped gently on the swells.

On clearing the protection of Hartland Point, it became clear that the forecast had been incorrect. We ran straight into a Force 6 south-westerly.

An hour into the journey, we were joined by a pod of 15-20 dolphins – a magical sight at any time. Everyone was caught up in the excitement.

Babies alongside mothers tracked our wake for an entrancing 10 minutes or so as we continued to pitch against the swell.

The second half of a journey in such a sea is the part that tests stomach-linings. Silence and the swell. Swell and the silence. Pitch and the wave. Wave and the pitch.

The drone of the powerful engines and the intermittent whiff of diesel fumes soon had Fiohann’s kippers attempting a coup.

They won, and I spent the next 20 minutes reassuring him that it would feel better when he was done, and that he probably wouldn’t suffer again.

Fiohann spent the last leg of the journey curled up with his eyes closed, his face slightly yellow.

However, the first matter to sort once at Lundy island was lunch. Clive took us outside the no-catch zone and gave us handlines and rods.

Within moments the first mackerel were wriggling in a bucket, and within 20 minutes we had about 20.

Clive coats these in breadcrumbs and herbs from his garden and cooks them while you dive. That’s freshness!

Then we were off to Gull Rock. Diving with seals – or rather seals diving with us –was not guaranteed. I had enjoyed only one brief encounter on a past visit.

I WAS FIRST IN AND AWAY towards the cliffs. Visibility was very good, as it often is at this time of year.

The trick with seals is not to look for them. Just settle down at 4-5m and wait without looking around.

I did this, and within a minute felt a tug on my left fin. I turned slowly to see a big playful seal nibbling it.

Sometimes facing them causes them to back off, but not this one. It simply rested its head on my knees, gently mouthing at creases in my drysuit.

When the other divers joined me, the seal swam off to greet them, like a big soppy dog.

Then others joined in, swooping and diving and twisting around in the shafts of sunlight.

People wonder at seals’ agility and watermanship when they see them on screen, but interacting with them in the water is something else.

I have swum alongside blacktip reef sharks; done somersaults with mantas; filmed free-swimming octopuses at close range; been accompanied by dolphins on dives and had a humpback whale surface under my boat, all magical experiences.

But being with Lundy’s wild seals counts among my most thrilling and transfixing underwater encounters.

Some say that divers should avoid physical contact with sea creatures, and I would largely agree. Nobody, however, has told the seals to avoid physical contact with humans.

Even if you could communicate this, my guess is that they would take no notice. I have never known such attentive creatures.

There were a couple of occasions when the seals simply zoomed to a stop not an inch from my mask and then started nudging with their noses.

This left me reaching for my octopus to give them a quick purge, sending them somersaulting backwards. They soon came back to play some more.

THERE WAS PLENTY OF OPPORTUNITY to fill my memory-cards. Andris caught shots of the seals’ tonsils as they tried to nibble his camera lens.

After 90 minutes we returned to the boat – but not without a couple of seals trying to pull us back by the fins.

Back on the Jessica Hettie, we reflected on our incredible dive while munching on freshly cooked mackerel in breadcrumbs and rosemary. Marvellous!

We had a little time left before offloading our camping gear and tanks for refilling, so I took Fiohann, by now recovered from the kipper incident, to snorkel with the seals.

He donned wetsuit and snorkelling gear, while I kept my dive-kit on.

Within moments of me reaching 4.5m one of several seals broke out to satisfy its curiosity about Fiohann flapping at the surface.

I watched the seal swoop up to within inches of him, twist away at the last moment and dive back down before turning back up fast – then contact!

Caught on camera was a smiling seal with its front flippers holding onto Fiohann’s ankles – an extraordinary and intimate moment of contact, and not short-lived.

Fiohann turned to see the seal, and was even more elated than me. I kept thinking: “How amazing an experience to be shared between father and son!” That rare moment will remain with us both.

The seal cavorted between us, making voluntary contact for about 20 minutes. By then hypothermia was creeping into Fiohann’s badly fitting wetsuit, and it was time for hot tea back on the boat.

On landing we found that the island’s Land Rover had taken our gear up to the campsite. We were left to walk, an introduction with every step to the beauty and ruggedness of Lundy.

It’s a steep climb, however, and Andris was some way behind. He is built for stamina in a zero-gravity environment without steep inclines – or perhaps he’s happy to allow the more eager into the bar first, so that they can greet him with a well-earned but bought-by-others pint.

Apart from the village, Lundy has two lighthouses – the Old Light and the newer one. The Old Light can be rented by the week and is one of the most enigmatic places I have ever stayed in.

It was built on Lundy’s highest point to protect the many ships that would collide with the island in bad weather – yet ships carried on colliding with the cliffs.

It gradually became clear that the worst collisions happened at times of high westerly or south-westerly winds combined with blinding low cloud or sea-mist that effectively rendered the Old Light invisible.

Hence the newer one on the lowest headland on the southernmost tip of the island.

The times with and without the Old Light have provided divers with a number of interesting wrecks, but the Montague is in a class of its own.

The biggest wreck in the Bristol Channel, this was a massive dreadnought of the mighty British Fleet, but hit the south-west corner of Lundy on a moonlit night in 1907.

Its massive remains are scattered among the kelp fields in no more than 10m.

AFTER A COUPLE OF PINTS and dinner in the Marisco Tavern, we retired to our tents in a wind that was clearly rising.

I was woken at 3am by the rain lashing down on the tent, driven by a Force 8 gale. Nothing was audible above the hammering of water and flapping of tent fabric.

When we poked our heads out of the tent into the still-strong westerlies the next morning, I noticed that there was another tent in our group – a small green thing.

Dave’s tent had collapsed. Every carbon-fibre pole had exploded in the force of the wind, forcing Dave and his son to evacuate and put up their spare two-man tent.

We packed up, dumped the exploded tent in a skip and went diving.

Clive reckoned the wind was still at Force 7, and was doubtful about being able to make the return crossing later in the afternoon as planned.

This worried me, as I was due to fly to Turkey for a two-week holiday on Monday evening.

Because of the weather, we stayed close into the east side of the island to dive the Knoll Pins, two great pillars of rock rising from 32m to break the surface at low water.

Connected by a narrow saddle at about 9m, the Pins stand clear of the cliffs and right in the tidal flow, so are covered in life.

Large kelp fronds down to 12m give way to deep and dramatic gullies in which dogfish snooze.

Brightly coloured cuckoo and larger wrasse swim between the fronds. Off in the current are shoals of bib and pollack.

At 25m I found a conger peeping from under a great rock and, as I got close, noticed a lobster by its side.

Going round to the side I was able to put my hand in behind the lobster, which shot out and whooshed off backwards. It’s quite rare to see them free-swimming.

We progressed upwards to the east side of the Pins, with sheer walls covered in Devon cup corals and bright jewel anemones, and more dogfish on ledges.

We turned the corner, heading west now, arrived at the 9m saddle linking the two Pins and passed through ready to surface on the north side.

WE ATE OUR MACKEREL lunch in the shelter of Gull Rock, then dived with the seals again. It was even better than the day before, and there were more. We danced and swam with them for over an hour.

After the dive, my son asked Clive whether seals ate seagulls. “No, they have no interest in them,” he replied.

Fiohann had asked the question because a pup had followed us out to the boat and was swimming gently around.

A big gull sat nearby in the water, waiting for any scraps from the mackerel.

We all watched as the baby seal snuck up behind the gull and lunged at its tail feathers, causing it to flap in alarm.

In 30 years of taking divers and fishermen to Lundy, Clive admitted that he had not seen that trick before.

We motored back to the jetty to pick up our camping gear. Clive had decided to make an attempt at the crossing.

It wasn’t smooth, but at least we were not head-to-wind, and it would be another hour before the waters were whipped into a frenzy by the effect of wind over tide.

Clive used the 15ft swells to push the Jessica Hettie towards Clovelly. At times we were surfing down them, touching speeds of 16 knots. No-one was seasick, and everyone enjoyed this voyage.

It had been a fantastic weekend.

It’s not just the diving that makes the trip to Lundy worthwhile – it’s the whole experience of Clovelly, the Marisco and a load of laughs amid the unpredictable weather, safe in the care of one of the UK’s most experienced charter skippers.

With the British weather there are no guarantees, but when you do get to dive Lundy you can guarantee some unique diving experiences. Pray for good weather, persevere and go there.

A day-trip for six divers aboard Jessica Hettie costs £420, or a Lundy stayover £390, clovellycharters website.