FREE DIVER

Also read: Underwater photographer who doesn’t get wet

freediving has introduced me to a community of amazing people and enabled me to travel to some incredible destinations around the world – including some pretty odd locations that I would never have visited otherwise.

Most notably, freediving has shaped my photography, giving it a purpose and a sense of narrative coherence.

However, my story started in a very different way. I was originally a scuba-diver – obsessed, and getting in the water whenever/wherever I could.

Scuba was what I really enjoyed about my marine-biology research and career – being able to get close to the wildlife was always special.

I undertook scientific diver training and a divemaster internship, and this led me to volunteer on a project filming thresher-shark behaviour in the Philippines.

Scuba was fast becoming my life – until it all took a turn for the worst.

One day, after a normal day’s diving,

I was overcome by lethargy and my vision became distorted – classic signs of decompression illness (DCI).

Initially I tried to deny it, knowing that it would be the end of my trip, but when breathing pure oxygen did nothing to alleviate the symptoms, I knew it was time for a stint in the decompression chamber to sort me out.

Two six-hour sessions later and I was good to go – but it wasn’t until I arrived safely back in the UK that doctors told me the bad news.

I had suffered a Type II DCI, where nitrogen bubbles affect the nervous system. Any remaining scar tissue could be “sticky” for nitrogen bubbles, making a second accident much more likely. This effectively ended my scuba career.

All was not lost, however. I read up on freediving and realised that it could be the answer. DCI is still a possibility for freedivers who go very deep, but because you’re not breathing compressed air, the risk is hugely decreased. So I travelled to Thailand to train in freediving.

as a freediver, i spend most of my time at depths of 20-40m. Many freedivers can go a lot deeper than that but I find that in this range there is an abundance of light, wildlife and scope for exploration. It’s at these depths that I get my best photographs.

I can hold my breath for about six minutes but, if I’m actively swimming, I must admit that my breath-hold never exceeds about two. And considering how unpredictable wildlife photography can be, two minutes to get your shot doesn’t seem a particularly long time.

You’d probably think that, for this reason, scuba-diving would be a better bet for getting amazing shots – but I don’t think it is. Taking photos as a freediver does have its challenges, but I believe it’s the constraints this approach presents that make it such an interesting mechanism for photography.

Short dive-times require you to be immediate, decisive, and to know your equipment inside-out. You don’t have time to wait around for the animals to do whatever you want them to do. You have to be prepared to make adjustments to the shots you were planning.

You are also fast, nimble and silent, compared to your tank-laden counterparts. In my experience, most animals will allow you to approach much more closely because of this, tending to be entirely uninterested or no more than mildly intrigued by your presence. They might be cautious, but they rarely appear afraid.

Freediving also allows you to explore the three-dimensional space of the water column more freely, where scuba-divers have to follow a strict depth profile, involving an initial descent to the deepest point of the dive, followed by a gradual but constant ascent.

Freedivers can move up and down at their leisure, albeit for a much shorter period during each dive. This improves your ability to move with the wildlife, respond to changing terrain and seeking out unique vantage points.

ultimately, i think the most important gift freediving grants the photographer is diminished control. You don’t have time to sit and wait for the perfect moment to pull the shutter, so the influence of chance is amplified.

In most circumstances, the greater the role of stochasticity, the happier I am with the image – it feels more collaborative.

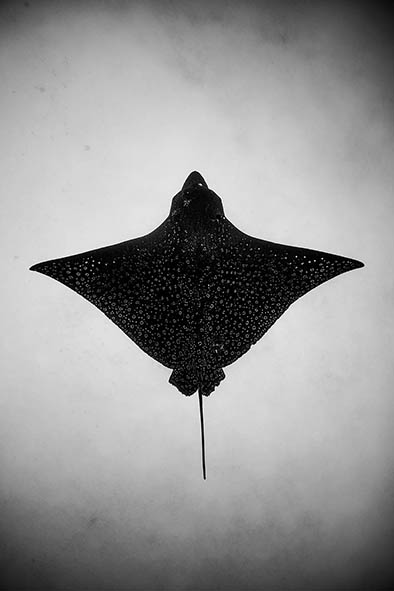

I shoot all my photographs in black and white. I wish I had some cerebral, high-concept rationale for this, but the truth is, it’s never really occurred to me to do anything else.

I’ve never wanted to take those classic well-lit, saturated, colourful and super-clear photos. They’re beautiful and require a lot of technical skill, but I find it hard to connect with them emotionally, and they don’t represent my experience of the ocean, which can be very appealing, but also overwhelming, humbling and intimidating.

Often it’s a dark, murky, disorienting and surreal atmosphere, a side of the experience I think is important to share.

Black and white helps with this. It can also make taking photos a lot easier when there isn’t much light or colour, which is an issue if you’re deep and choose not to use artificial light.

I shoot with a Nikonos V camera with a 35mm waterproof rangefinder. It has a rugged reliability – and amphibious capabilities – which make it ideal for freediving. Plus, its small form-factor creates very little drag, which is essential for streamlining on a dive.

I shoot with highly sensitive, grainy black-and-white film, using only ambient light. This is partly because I love the aesthetic of having no external lights, but partly because I had none when I started out, so had no choice!

I have incorporated digital into my work but I’ve never been able to tear myself away from this minimalistic approach. I love the focus it places on physical form, the differences and similarities between animals.

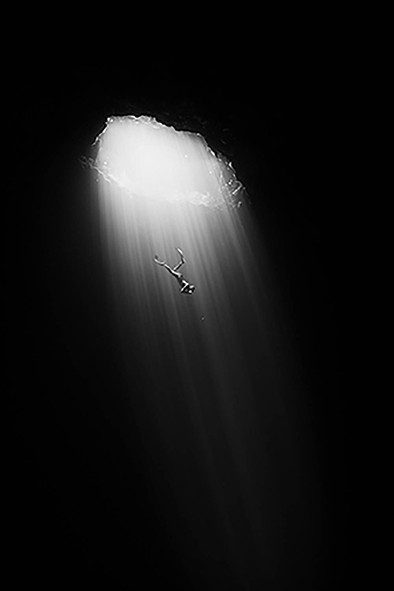

for photographic opportunities with freedivers, you can't beat the cenotes in Mexico. Cenotes form when limestone caves collapse, revealing beneath them groundwater pools that are considered to be sacred gateways to the Mayan underworld Xibalba.

There are thousands strewn across the Yucatan, each with its own unique shape, size, depth and colour.

The water is crystal clear, the sun pours into the darkness from the jungle above as rotating bars of light, and they’re enormous. It’s almost impossible to get a bad picture!

When it comes to shooting wildlife, my favourite animals to dive with and photograph are sea-lions. They’re incredibly playful and interactive, and their speed, agility and grace put us to shame.

One experience that really stands out was in the Galapagos. I watched two juveniles playing with a piece of reed they’d found, passing it back and forth and chasing each other’s tails.

After about 20 minutes they included me in their game, racing up, leaving the reed floating in front of me before careening off, disappearing for a few seconds and racing back to reclaim their toy. It was a special moment that I’ll never forget.

One thing I really like about my mono photographs is that they’re a geographic leveller. The style renders images taken in the middle of winter in the UK close to indistinguishable from photos from paradisal dive locations in far-flung locations.

People have this preconception that UK waters are murky and devoid of life, which UK divers know could not be further from the truth. When the conditions are good, the diving here is spectacular.

Unlike the tropics, temperate waters are dominated by seaweeds, so you get these beautiful hues of greens, reds and browns that you don’t tend to see elsewhere.

Even when the visibility isn’t great, these come together to create an eerie, ethereal atmosphere and I can’t get enough of it, to dive in and to shoot.

I know now that I would always have been drawn to freediving. Freediving and photography are so tightly interwoven into the different facets of my life.

The style has allowed me to develop a deeper connection with the ocean and to integrate with a small but global community of like-minded people.

I hope that when non-divers see my photos, it will encourage them to experience the marine environment themselves, and hopefully engender a sense of responsibility to protect it.

For more about James’ freediving experiences, visit discoverinteresting.