CRITTER DIVER

Sali Army

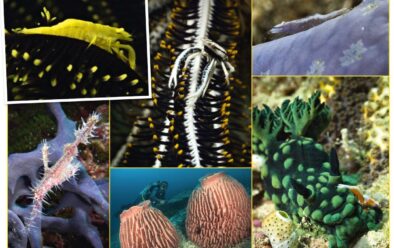

A mighty army of tiny critters, that is, at a near-virgin site in up-and-coming Halmahera.

JOHN LIDDIARD reports

Looking for critters in Sali Bay.

When reading an address, I tend to cut corners. If I know where a location is from the first line or two, I don’t need to waste my time reading the rest.

The first line tells me that Sali Bay is on Sali Island. Indonesia has more than 17,000 islands, so it’s hardly surprising that I have never heard of it.

The next part of the address is Halmahera. I haven’t heard of that either, but apparently it’s the biggest island in North Maluca. Maluca sounds familiar, but I can’t put my finger on it on the map.

Indonesia. Well, I know where that is. Looks like my short-circuited reading of addresses doesn’t work here.

Before Google Maps this would have entailed an outing to my local library to look through atlases. Nowadays, I start entering text in a browser search bar and, before I’ve finished typing, a suggestion comes up for me to click on. Ping. Now I know where Sali Bay is.

Even so, I know only because of the resort location. Google Maps doesn’t have its own label for the island.

For those with a bit of Indonesian geography imprinted in their minds, picture where Manado and Lembeh are at the northern tip of Sulawesi. Then draw a line just south of eastward to West Papua and Raja Ampat. North Maluca is the group of islands halfway between the two.

Halmahera is the largest island in the group. And Sali is a tiny blip between the south-west edge of Halmahera and the moderately sized island of Bacan.

A new diving location brings heightened anticipation. I have a pretty good idea of what to expect, but it’s not until the first dive that I confirm that for myself. It’s all about tiny critters.

We head along Besar island to a crooked inlet at Kubur. The top few metres are reef and from there downwards silty sand. Muck-diving without the muck.

My second photograph of the trip is a Halameda ghost pipefish, a ghost pipefish variation camouflaged to hide in the clumpy green halameda algae, so we’re off to a good start. If you’re wondering, I took a warm-up photo of a warty nudibranch.

There are four dive-guides in the water, with only two or three divers each.

Rather than disperse, the guides work as a loose team, staying at the limit of visual contact and communicating critter finds to each other. More than half of us are photographers, and as we trade subjects I barely have a free minute.

The weirder and harder to find a critter is, the better. The guides are all from Manado and know their stuff. A well-disguised solar-powered nudibranch fits the bill. Nudibranchs are fussy about their food, and those in this group enjoy soft corals, which contain symbiotic zooxanthellae algae. When nudibranchs eat the coral, rather than digesting all the zooxanthellae they keep them functioning to provide solar energy in their new host.

Kubur is a dive-site that is always well out of the current; other sites are a bit more fussy. Sali and nearby small islands half-block the narrowest point of the channel between Bacan and Halmahera, creating a choke-point through which 2m of tide funnels.

Manager Stefano tells me that’s why he and his two business partners selected the location: well-fed marine life and no-one else dives there. No resorts.

No liveaboards. No-one.

Well, I suppose at least one of them must have gone past in a boat and given it a go at some point before they leased the land and started building the resort, but for a diving tourist this is near-virgin territory, open only since 2017.

Again on Google Maps, the satellite picture shows nothing but trees. The nearest town of any size is an hour away by speedboat.

Appeared in DIVER July 2019

The current between the islands can really boil. I feel the dive-boat kick as it crosses the whirlpools. Not that we dive in that sort of current – if we arrive at a site to find that the flow is not quite as predicted, we move to another site nearby.

If it’s a previously undived site, you might even get to name it.

The strongest current we experience under water is easily manageable. We have a little shadow from a headland that sets up a gentle counter-current inshore from the main flow. Many places wouldn’t even call it a current. We dive there because the original choice of site on the other side of the headland looked a bit hairy.

The dive-briefing provides a choice. Down the reef to 15m, then right shoulder for more reef, or straight out onto the sand. Every diver on the boat opts for the sand, and our guides work their critter-finding magic.

I’m called away from a seafan-munching nudibranch to a trio of subjects within inches of each other. A 15mm cockatoo waspfish looks like a snap of dead neptune grass, so much so that after the dive I find that other photographers have overlooked it while concentrating on the pair of dwarf pipehorses hanging onto the hydroid beside it.

To visualise a dwarf pipehorse, imagine a pygmy seahorse that has been stretched out and painted a dirty brown. Rather than hanging onto gorgonians with their tails, they hang onto scraps of weed and hydroid with an equally shy expression.

Our guides find pygmy seahorses on at least every other dive, and three species. Most common is the classic Bargibant’s variety, covered in large textured tubercules and coloured from deep pink to an off-yellow to closely match their gorgonian habitat.

Gorgonians don’t always have their polyps out, and Denise’s pygmy seahorse has cleverly evolved to match a gorgonian with polyps retracted.

It has an embarrassed expression, like that of a shaved cat.

Pontoh’s usually lurk a little shallower, so we find them towards the end of a dive, hanging onto hydroids among sponges, tunicates and other growth.

These little beauties, a weedy orange-yellow with white bellies, are much more difficult to photograph.

Another diversion to an alternative site comes about for a different reason. The plan was for a traditional muck-dive on a black-sand slope in front of a local village, so our guides go ashore to get the village chief’s permission.

Trouble is, he is still sound asleep and must not be woken. Perhaps he had a late night. We head for another site. A day later we start at a different village for some black sand and a chief who is awake.

It isn’t all about critters. As our guides say in their briefings, they will find us the macro subjects and we can look out for the big stuff such as sharks, rays and turtles for ourselves. We just need to keep an eye out into the blue. But at 20m, do I really want to interrupt photographing a frogfish to stalk a couple of large blacktip sharks patrolling at the limit of visibility?

A safety stop at Jalan Musak II provides an easier decision to head out into the blue among a shoal of batfish that have spent the whole dive patrolling above us.

I had tried to get close to them at the start of the dive and they were timid, so I go back to the reef for a peacock mantis shrimp and the novelty of a colony of coral-burrowing hermit crabs. By the end of the dive the batfish above are so used to our noisy bubbles rising past them that I can get right in among them.

Back at the jetty, the tide is out. With low-water springs and a 2m tidal range, the shallow corals poke well out of the water. Looking down from the jetty, reef-fish can be seen trapped in pools.

Millions of years of evolution mean that they’re used to it.

I’m four days into my stay before I get to dive the house reef. On previous afternoons we have taken the boat out because either the tide was too low or current was swirling round the bay, and both combined to mess up the visibility.

It might be a good house reef, but it isn’t always the best option.

For the easiest way to dive it, we have left our dive-gear on the boat from the morning dives. We walk down the jetty, step into the boat, kit up and fall off the other side. The end of the jetty is built out to the reef crest, so the beam of the boat puts us a few metres further out over deeper water.

A giant moray eel tucked under the first coral-head is almost a forgotten bystander compared to the residents of a gorgonian on the other side of the rock, and even that provides a choice: on one side a pair of ornate ghost pipefish, on the other a pair of Schultz’s pipefish.

Big barrel sponges are host to barrel-sponge squat lobsters; tiny, purple and hairy. At some locations they hide away and take patience to find. On the dive-sites some barrel sponges are infested with squat lobsters. If only the pushy speckled hawkfish would stop photo-bombing as I try to line up on these hairy photogenic cuties!

Another cutie on the house reef is a yellow coral crab. I wouldn’t expect to see a crab like this in the open in daylight, but late in the afternoon it’s getting dingy enough for it to sit happily on its yellow tunicate and pretend I haven’t seen it while I flash away. In fact I wonder if it’s just a carcass, until it eventually moves.

I am constantly amused by how divers react to the way creatures prevalent in some places are rare in others. I bet the first diver to see a lionfish off Florida was excited to see it. Here a lionfish is not that common, but I can’t really be bothered.

Yet an arrow crab is worth some time, even though at a glance I can’t tell it from the arrow crabs prevalent in places such as the Canary Islands.

Spending an hour at 12-15m, I suppose we could have ventured further than the small area of sandy slope and coral-heads we cover on the dive, but there is no need.

After such a shallow dive a 5m safety stop is hardly necessary, but I treat it as an opportunity to continue spotting nudibranchs right up until we surface back beside the boat.

The easy exit is up the boat-ladder and back onto the jetty. So do I classify this as a shore-dive or a boat-dive in my logbook?

What excites a critter-hunting diver more than a tiny critter? A tiny critter on a critter. Being pedantic, most marine life are animals and such a description could equally apply to pygmy seahorses on gorgonians and many more of the usual suspects, so perhaps I should say critters on critters on critters, or critters on critters that move.

Yellow and orange emperor shrimps on sea-cucumbers are almost commonplace, but tiny blue emperor shrimps on blue starfish bring a different perspective, and an orange emperor shrimp on the spotted green nose of a crested nembrotha nudibranch is as cool as emperor shrimps get. The tiny purple blob of a passenger on the dusky white side of dark margin glossodoris is at the extreme.

I have to zoom in on an already close photograph to 1:1 pixels before I can distinguish the legs and carapace of a purple creepy-crawly I can’t identify.

I don’t think it resides there, but was perhaps picked up from red algae as the nudibranch brushed past.

Passengers on echinoderms also extend to featherstars or crinoids. Their commensal shrimps and squat lobsters are usually well camouflaged to match the bristly fronds of their hosts, but occasionally we find one out of sync, such as a yellow shrimp on a black crinoid, or a black-and-white-striped squat lobster parked at an angle, so that the stripes are not lined up with the markings on its black-and-white crinoid host.

The various warty nudibranchs are common, so not that exciting, but how about one working its way along the nose of a lurking crocodilefish?

While my interest at Sali Bay is in the macro, we do see other stuff: healthy reefs with litter a rarity and a good selection of reef fish, moray eels, lionfish, triggerfish, snapper, sweetlips, bumphead parrotfish, shoals of trevally, amberjack, sharks, eagle rays and turtles.

It’s just that macro is where the dives here really grab me. Finding the next critter is exciting.

Unsurprisingly, my week finishes having seen no divers other than those at the resort, no other day dive-boats, no liveaboards and barely any boats at all, except for the little wooden runabouts the villagers use like mopeds.

Near-virgin diving at its best.

FACTFILE

GETTING THERE> John Liddiard flew with KLM via Schiphol to Jakarta, then Lion Air and Wings Air to Manado and on to Labuha. Transfer to Sali Bay is then 30 minutes by bus and 60 minutes by speedboat.

DIVING & ACCOMMODATION> Sali Bay Resort, salibayresort.com

WHEN TO GO> October through to May are the best – stronger winds and choppy seas are most likely in July and August.

MONEY> Indonesian rupiah.

PRICES> A 10-nights, 16-dive package with full board at Sali Bay including flights and transfers costs from £3345pp with Dive Worldwide. An overnight stopover might be required, diveworldwide.com

VISITOR Information> indonesia.travel