What do you do when you have time to spare in Indonesia? Pop over to Vanuatu to dive one of the world’s most iconic wrecks, of course. It only took BRANDI MUELLER four days to get there.

Also read: Photographic expansion at Diving Talks

Not that many people go to Vanuatu on a whim, but I happened to find myself in Indonesia with 10 days to spare.

Vanuatu didn’t seem too far from Bali, but I found out that it wasn’t exactly direct. My flight path was Bali, Singapore, Fiji, Port Vila and finally, Luganville; home of the President Coolidge.

It took four days, overnight layovers in three countries and $400 in excess-baggage fees, but I arrived in Santo at the break of dawn. I was exhausted, but excited to be there.

The tiny airport’s baggage claim consisted of a table where luggage was stacked and people grabbed their things. I went out to meet my driver, and after loading my bags we were off to Coral Quay’s Fish & Dive Resort.

Ten minutes later I was checking into my room and putting my camera together to go out diving, all before 7am.

Vanuatu became independent in 1980, but before that it was known as New Hebrides, a group of islands co-governed by the British and the French.

When WW2 started in the Pacific the island of Espiritu Santo (Santo for short) became an important base for the Allied war effort. Although it never saw battle, hundreds of thousands of troops passed through, and the island was changed forever.

President Coolidge

My gear was loaded onto a pick-up that had seen better days, and we set off. It was soon clear that the shape of the truck was circumstantial, because of dirt roads with more pot-holes than smooth spots, and as other cars passed we rolled up the windows to reduce the dust.

We backed up almost to the water’s edge. There was a small building with tanks and gear, and we set up our kits near the shoreline and simply walked in.

It seemed an unceremonial entry to see one of the best wrecks on Earth, but the sun was shining, the water was warm (28°C), and I was about to see the Coolidge!

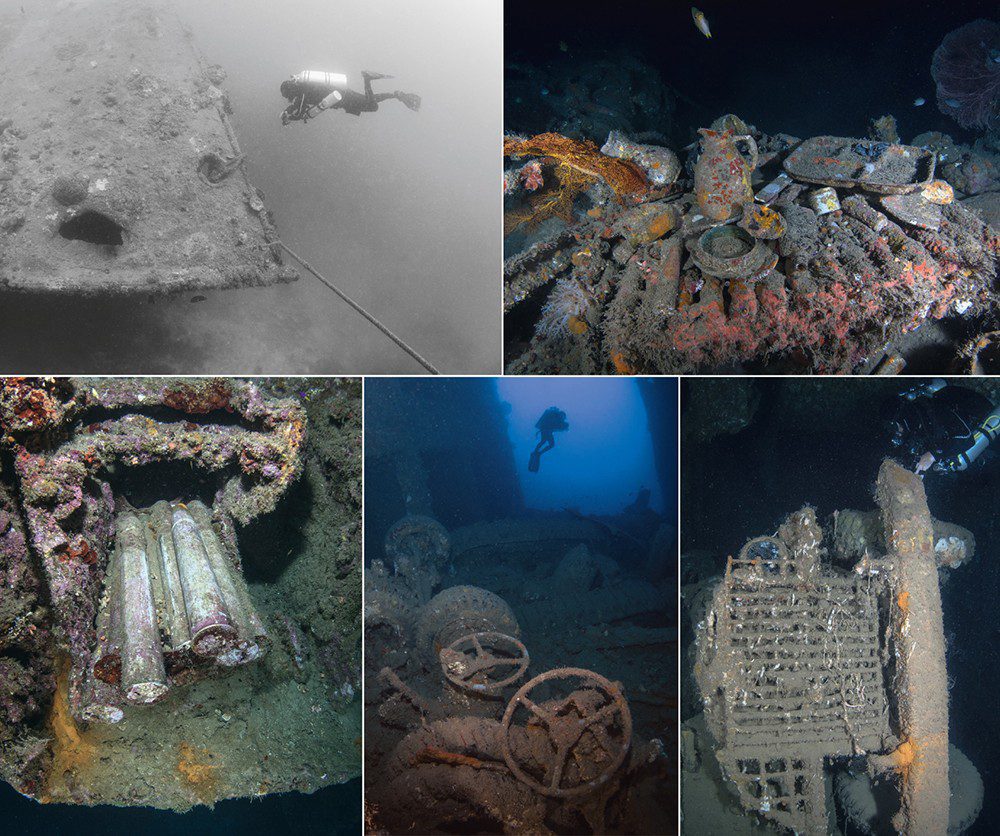

Under water, my first view of the 199m-long, 25m-wide former luxury cruise-liner and warship was a massive shadow. As I got closer, the bow started at about 21m depth and hard corals were growing on the hull.

Resting on the seabed on a steep slope, the stern sits in 70m, but we wouldn’t be visiting that on this dive.

We swam along the top deck which, because the wreck lies on its port side, feels like a wall-dive.

I could make out the two guns on their platforms, on the shallower one a stack of shells. Then I saw my guide disappear into the first cargo hold.

The Coolidge began her journey as a liner on completion in 1931, transporting society’s well-heeled passengers around the world until 1941.

Then she was put into war service, and was fully converted into a troopship. A lot of her finer points were removed or boarded up, such as the beautiful glass light-fittings and a certain famous porcelain relief wall decoration known as “The Lady”.

The Coolidge was carrying more than 5000 troops and packed with supplies to support the war. This was evident from a pile of trucks and machinery strewn below us in the hold.

Steering wheels and tyres stood out as the most identifiable, and my guide produced a gun encrusted in marine growth and directed me to a pile of artefacts that included pitchers, serving trays and flares.

We continued to explore until our bottom time ran out and we went shallower, finishing by swimming over the hull back towards the bow.

A pile of ammunition lay scattered, and my guide stopped at a large cooking-pot sitting next to guns laid out for divers to see.

He removed the lid of the pot, and inside was a treasure-trove of artefacts.

A gas-mask, Coke bottle, ceramic dishes, shoes and other bits and bobs were piled inside.

Feeling fantastic after the first dive we swam back to shore and walked the rest of the way out. But I was ready for more.

The next morning we headed down the same pot-holed road and, after my tech cert cards had been checked, I added more tanks to my kit to visit the engine-room and, I hoped, “The Lady,” both beyond recreational-diving depth-limits.

“The Lady” originally hung in the first-class smoking lounge, but it wasn’t found in the wreck for many years.

Allan Power, a bit of a Vanuatu/ Coolidge legend, was inside it one day and caught a glimpse of something he’d never seen before. Probably covered for protection, the wood must have rotted away just enough to make it stand out.

At one point she was salvaged from the wreck, but was later returned and now hangs at around 42m.

For this dive we did a much longer surface-swim to start closer to the stern, and hauling extra tanks and my camera made for slow going. But we finally got to our descent point and headed down.

A large opening had been cut into the hull to give easy access to the engine-room, and we dropped to 40m, almost directly on top of the boilers and the massive gauge panel.

My guide Tom twisted and turned through the engine-room, pointing out wrenches and machinery and taking me through other hallways in the ship.

There was a row of toilets, and in one passage he slowly brushed the silt off an object to reveal an etched-glass light-fitting. I was so excited that I was smiling through my regulator (and maybe just a little narked) and had completely forgotten what we were looking for.

Tom stopped in front of me, and I thought: “Why are we stopping? Keep going, show me more!” He motioned for me to turn. There she was in all her glory, still beautiful and paint bright after more than 75 years under water.

My computer showed that our planned bottom time was pretty much up, so we ascended and swam over the hull heading towards our deco stops.

The Coolidge’s demise occurred on 26 October, 1942. The captain was not given information about the minefield in the channel approaching Santo, and the ship struck a mine near the engine-room, and another near the stern.

The captain ran the ship aground, and the crew of more than 5000 managed to flee before she sank 90 minutes later. Only two lives were lost.

The Reef

Taking a break from the Coolidge, the next morning we headed out for two reef dives. The lush, green island of Santo looked spectacular during the 45-minute ride under blue skies. Back-rolling off the boat, I immediately saw a beautiful reef of hard corals below.

Getting closer, however, exposed another story. I swam down to a massive table coral, and found that half of it was white and the other half covered by at least 15 crown-of-thorns. These predatory starfish feed on coral polyps and have venomous thorns.

In small numbers it’s likely that they support the reef by killing off sick or weak corals and making room for new, stronger corals to grow, but occasionally they have huge outbreaks, and their large numbers can then be detrimental.

From a few metres above, this reef appeared fantastically healthy, but looking closer it seemed that the starfish might be destroying it right before my eyes. Tom had been near this site a week earlier and was concerned.

Starfish regenerate, so they must be killed completely or they can come back as multiple stars. He was armed with syringes and vinegar, which is thought to kill them without harming other marine life.

I ended the dive feeling sad about this remote and rarely dived location. What if these outbreaks happen in other locations no one sees? How can we fix it? I felt a bit hopeless about the state of the world’s reefs, but was impressed by the efforts of one person, trying to protect this reef.

Far from discounting the reefs of Vanuatu, our second dive in a different location was pristine and with far fewer crown-of-thorns.

I left the reefs feeling the same as I had on the Coolidge – there is so much to see and explore under water and just not enough time.

USS TUCKER

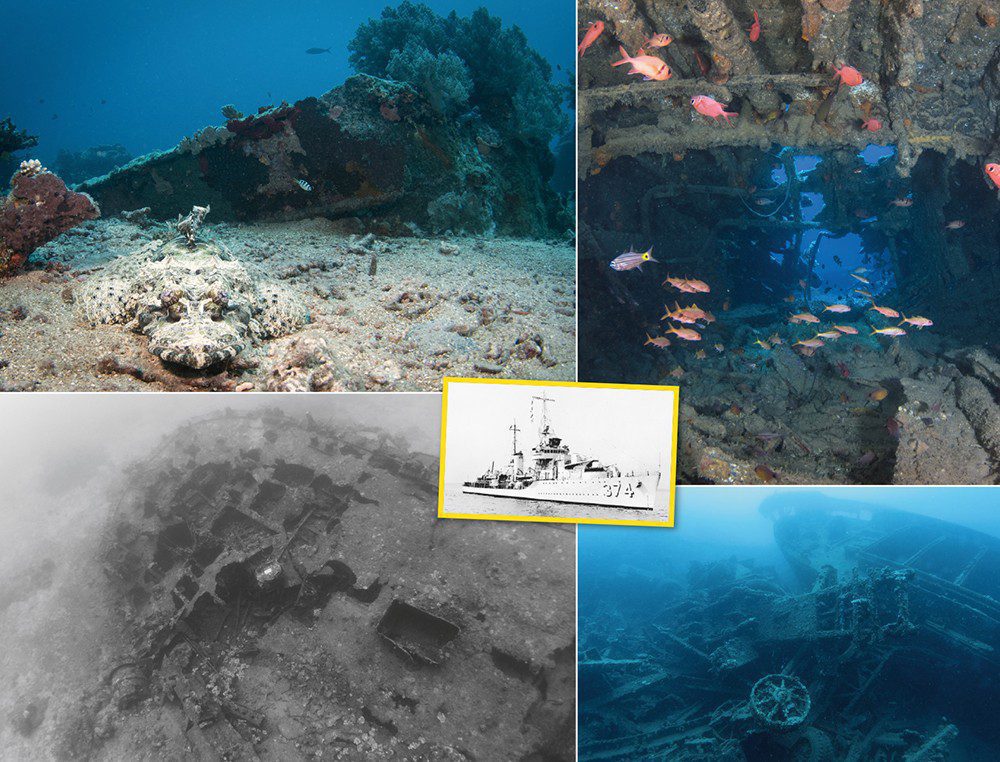

Just a short boat ride from Luganville lies the USS Tucker destroyer. It seems slightly ironic that this ship was also sunk by a friendly mine just three months before the Coolidge.

She was leading a cargo ship into Santo on 4 August, 1942, the crew unaware that a minefield had recently been laid, and was torn in two, killing three men.

At 104m with an 11m beam, she is set in sand at 20m, broken into many pieces but covered in marine life.

I did two dives, exploring fragments that are now homes for fish, including several semicircle angelfish, emperor angelfish, large puffers and sweetlips.

The remains of metal were coated in red and orange sponges and lots of coral.

My guide pointed out three crocodilefish, all of which I had missed because they blended in so well with their surroundings.

Million Dollar Point

Another dive on my list was Million Dollar Point, and its story is often told with a sinister tone.

After the war ended and the Americans were leaving, they offered to sell the machinery to the British and French very cheaply. The colonial powers refused to pay, figuring that the Americans would leave it behind anyway.

In an act of spite, so the story goes, the Americans pushed millions of dollars’ worth of perfectly good machinery into the ocean.

In his book The Lady and the President, Peter Stone does not relate the action as spiteful, merely as the way of the world at that time. The war was over; transporting the machinery home would have been costly and taken up valuable space on ships that were needed by troops.

Besides, bringing all that equipment back to be sold off cheaply would have created a surplus of low-price machinery, and it was more important to grow the economy by selling people new products.

Still, it did seem a waste to throw it all into the ocean instead of helping a poor country in which life was transformed during a war it didn’t ask for (and, of course, today we know how detrimental to the marine environment such dumping can be).

Coral Quay’s pick-up drove me to a lovely beach, with food and drinks for sale, numerous sunbathers and kids playing in the white sand.

Setting up our gear on a picnic-table, we walked into the small waves, past local children who paused to stare at us in our strange dive-kit.

The shadow of machinery was hard to miss. Swimming closer there was a large ship (that might have sunk trying to salvage the equipment), bulldozers, cranes, fork-lifts, small boats, trucks and more. I felt terrible that this garbage dump existed. Shouldn’t we take responsibility and clean it up today?

Seventy-five years on the garbage is still there, in the same condition, and will be for generations. I noticed rubber tyres that appeared ready to drive their ancient machinery away.

Coolidge & Kava

My last day of diving was on the Coolidge. We visited the medical supply area. Stone discussed that malaria was the biggest killer of soldiers in New Hebrides. Four in 10 became infected, and for every gunshot wound there were eight cases of malaria.

All quinine in the area was ordered to be sent to Santo, and the Coolidge was carrying more than 250kg of this important medication, much of what was left in the South Pacific at the time.

A doctor on Santo, watching the ship sink, asked that divers do everything they could to recover the medication from inside the ship, but none was.

It’s still there today. Swimming through a corridor, to one side of which were what looked almost like shelves, I saw bottle after bottle of different colours, many with powders still sealed in them.

Back on land, dive-gear drying in the sun, I enjoyed lunch and coffee by the pool while reading more of Peter Stone’s book, and I was even invited to do some “cultural research” at a kava bar later that evening.

I had tasted the dirt-water made from the Piper methysticum plant, known as kava, on Fiji and other Pacific Islands, but I had heard that Vanuatu has the best, so of course I was going to join them.

Luckily for me, women are allowed to partake now, though I was still the only female among a mixture of expats and local males.

As advertised, my mouth got a little numb and I felt very relaxed. After the second shell I did feel a little tipsy, but it wore off quickly… so I had another.

My flight departed just after dawn the next morning, and I managed to find myself back at the tiny airport, with a touch of a headache caused by residual kava and rum.

I’m pretty sure that this unique group of islands will be in my future again someday – there is so much more to see, and many other islands to explore.

FACTFILE

GETTING THERE> Brandi flew AirAsia from Bali to Singapore, then Fiji Airways to Nadi and Port Vila and Air Vanuatu to Luganville (Santo). From the UK it’s easiest to fly to Brisbane; Air Vanuatu has a direct flight to Santo once a week.

DIVING & ACCOMMODATION> Coral Quays Fish & Dive Resort, coral quays.

WHEN TO GO> Year round. April-October is driest and coolest with water temperatures of 24-26°C, November-March is the rainy season with water temperatures of 26-29°C.

MONEY> Vanuatu vatu.

HEALTH> Anti-malarial medication may be suggested and it’s important to prevent mosquito bites as viruses such as dengue have occurred. Vaccinations including typhoid are recommended. Port Vila has a recompression chamber.

PRICES> A five-night, eight-dive package at Coral Quays starts at £566 (two sharing).

VISITOR Information> vanuatu.