PIONEER DIVER

Return of the Amphibians

Marine biologist Lauren Smith has made a connection with diving history

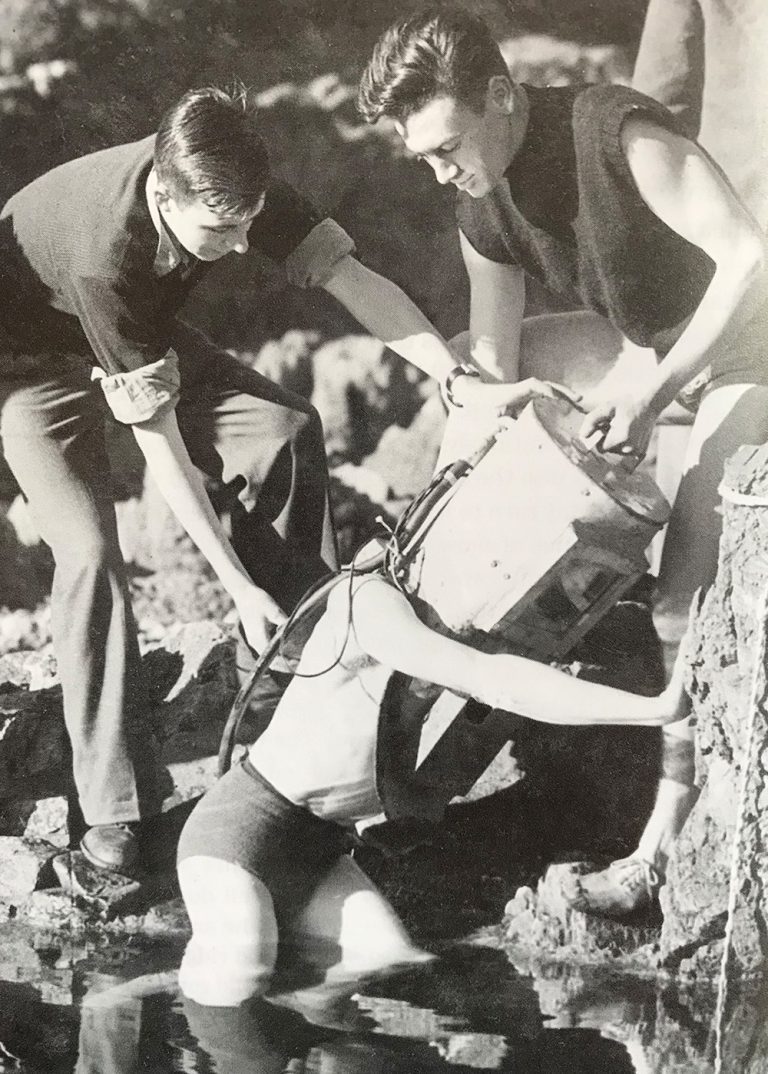

Amphibian Alf Goodwin about to submerge with the dustbin helmet at Souterhead, helped by Les McCoss and Laurie Donald, in 1946.

Appeared in DIVER August 2019

Scotland 2019

I am about to dive in the North Sea, with my new drysuit and the rest of my kit, fresh from being serviced. As I drop below the surface, I reflect on the remarkable ease of scuba-diving today, compared to my friend’s experiences a mere 74 years previously.

That friend, Ivor Howitt, is I believe a true pioneer of recreational scuba-diving both in the UK and Australia. Yet until the late 1990s his story had remained largely untold. And what a story it is…

Scotland 1945

A teenager at the end of the war, enthused by William Beebe’s descriptions of the underwater world, Ivor was determined to go diving. Scottish temperatures, lack of equipment and training did little to put him off. Instead he improvised with the materials to hand.

He modified a Civil Defence gas-mask, and connected it to a motor car foot-pump with a length of rubber tubing.

Then, together with his friend Hamish Gavin, he went to a farm dam on a wintry day with frost on the ground.

They stripped off and took it in turns to submerge in the icy water, teeth chattering and almost paralysed with cold, to complete their inaugural dives.

Following this experience there followed plenty more inventions and adventures. A 1920s-style diving helmet was made from a sheet of copper wrapped around a dustbin lid, with 60lb of lead weights bolted in place.

Air was supplied via a garden hose connected to two pairs of car-tyre foot pumps. All of this gear was transported on push-bikes to Souterhead, a sheltered inlet a few miles south of Aberdeen, which became a favoured spot to test out equipment.

A war-surplus field telephone was fitted inside the helmet by another friend, Les McCoss, connected to a loudspeaker on land so that the diver could be heard.

Diving was fast becoming a core pursuit of Ivor and his friends, alongside their other activities, which included mountaineering (they were all members of the Cairngorm Club), rock-climbing on sea-cliffs, skiing and canoeing.

And so, in 1948, they formed a small club known as The Amphibians. It would be the first amateur UK club to include both freshwater and marine diving – the first freshwater-diving club, the Cave Diving Group, had been formed in the 1930s by Graham Balcombe and Jack Sheppard.

Ivor revelled in the task of designing and making all the club’s underwater breathing equipment.

In 1949 he wrote to the Dunlop Rubber Company, enquiring about the production of fins, because it had made naval frogmen’s fins during the war.

It did reply, but said that it “could see no commercial market for swim fins in peacetime”. The response, as Ivor noted, reflected the virtual non-existence of sport-diving in the UK at that time.

The Amphibians’ exploits soon brought the club to wider attention, and members were invited out to see a naval team charged with identifying the wreck of a 16th-century Spanish galleon, the Florencia, which had been sunk off Tobermory on the island of Mull.

In the course of this visit Ivor commented on the luxury of diving in a nice warm suit. This was noted by a junior officer, and not long afterwards the Amphibians Club became the proud owner of two old rubber frogsuits.

These, along with a couple of standard copper diving helmets condemned by the local harbour board as unsafe for further use, were paired with swim-fins (from a demobbed naval frogman). War-surplus kits designed for submarine escape were put to use as economisers, with air supplied from their home-built pumps.

It was with this set-up that the club-members began diving in a local swimming pool, and were able to begin experimenting with underwater photography and homemade housings.

A giant leap forward came in 1949, when Ivor purchased the British version of the Cousteau-Gagnan aqualung. This was the Siebe-Gorman compressed-air breathing apparatus (CABA) with cylinders mounted on a back frame, with reducing and demand valves and a pressure gauge. Corrugated air hoses connected to a simple mouthpiece.

Getting the cylinders filled was not straightforward, Home Office regulations wouldn’t allow them to be filled with air for civilian use, so instead the British Oxygen Company supplied pure oxygen, which meant that dives were limited to less than 10m.

Australia 1950

By late 1950 Ivor had completed his engineering studies and training, and decided to emigrate to Australia. It was time to realise his dream and try out his Siebe-Gorman in warmer waters.

While in Australia, he began helping police in search and recovery operations for drowning incidents – because at the time the police had no diving equipment.

By May 1952, Ivor took his first colour photographs while diving off Lindeman Island, in the Whitsundays, his precious camera and film encased within his homemade “cooking-pot” housing.

In November 1953, together with Bill Young, Ivor took some of the first underwater colour photographs of the Great Barrier Reef, using his Robot 35mm camera in a newly designed home-made underwater housing.

This housing featured a “reverse viewfinder”, which Ivor had designed to allow for the air-space within the mask.

There was a sunshade for the exposure-meter window, a tyre valve fitted to allow pressurisation and push-pull controls for focus, aperture and exposure time.

Ivor also had the foresight to include a gauze-covered container for soda lime to prevent condensation build-up.

In late 1954, a family emergency saw Ivor return to Scotland. After that he travelled to New Zealand, where he settled in 1956 with his wife Mary. His and the other Amphibians’ pioneering exploits remained dormant until 1999, when Dive New Zealand published his Memories of an Aberdeen Amphibian.

This was later followed by publication in 2007 of a book, Fathomeering – An Amphibian’s Tale. This, in Ivor’s words, is “in the main a personal record of the adventures shared and the equipment used by a few amateur divers in Scotland and Australia after the end of WW2 and prior to the explosion of interest in recreational diving in the mid-1950s”.

All of this occurred long before I came to know Ivor, but after learning about him (by chatting to someone at DIVE 2014, the NEC Dive Show) I got in touch.

I devoured the Amphibians Club tales of discovery and adventure, and soon realised that, having moved to Aberdeen myself in 2005, I had shared many of the same diving and hiking locations, albeit a good few years apart!

As parallels between our interests became clear, and having become aware of the incredible achievements of Ivor and his friends, earlier this year I asked for his permission to reinstate the Amphibian’s Club.

My mission is to continue our outdoor adventures and to honour the original members’ legacy. If you would like to find out more about the Amphibians Club or get in touch, please visit amphibiansclub.co.uk or catch us on twitter @AmphibiansClub