UK WRECK DIVER

Solved – the St Ives Mystery

MARK MILBURN turns detective once again to tackle a wreck conundrum in Falmouth Bay spanning two world wars

‘Looking for a needle in a haystack’. Inset: The St Ives.

THE TWO WORLD WARS saw numbers of British non-naval vessels called up for service.

Many fishing trawlers and drifters were turned into mine-sweepers, patrolling British ports.

The laying of moored mines by the Germans was relentless, as was the searching and destruction of them. In a two-week period between 15 and 31 December 1916 in the Falmouth area, 89 were destroyed.

The 145-ton trawler St Ives H11 was requisitioned on 3 March, 1915, converted into an auxiliary patrol vessel and entered naval service in May, designated 1192.

HM Trawler St Ives helped in salvaging the ss Keltier on 11 and 12 December, 1916. The crew would have received a share of the salvage award, once it had been sorted out with the insurers.

Then she struck a mine laid by UC17 somewhere in Falmouth Bay, with the loss of the commanding officer and 10 ratings.

Over the years, divers have searched for the St Ives. It took a while to find the Falmouth Commodore’s notification to the Admiralty in the national archive. It read: “Regret to report trawler 1192 St Ives blown up by mine two miles WSW of St Anthony Falmouth.”

St Anthony Point, with its lighthouse, is on the eastern side of the entrance to Falmouth harbour and is often used as a reference point. The area two miles WSW consists of coarse sand and was dredged for scallops for many years, so any remains would have been known, either as foul ground or where things had been trawled up.

Eventually, after much diving in that area, I found 12 cast-iron blocks. Around 30cm on each side and 10cm thick they seemed too big for ballast, which has to be movable, yet too few in number for cargo. What could they be?

Eventually someone who knew about old steam trawlers provided a plausible answer. When a trawler had a steam-engine and boiler fitted towards the stern, the weight would cause the bow to rise.

A vessel the size of the St Ives would need around 12 tons to compensate for this – the approximate weight of the blocks.

Then a local ex-diver told me a story about another wreck in the area, an oil-tanker called the Caroni Rivers.

Built in 1928 and weighing a hefty 7807 tons, she had left Falmouth Harbour for sea trials on 20 January, 1940, following repair work. Heading into the freshly mine-swept Falmouth Bay, she hit a mine laid by U-34.

All 55 people on board were rescued but attempts to tow the Caroni Rivers back to port failed and she sank.

Sections lay very close to the surface but the big wreck spent most of the war with buoys attached in the centre of the shipping lane into Falmouth Harbour.

In 1948, the 7450-ton Marlene was badly damaged when she hit the wreck, so the following year HMS Caldy cleared the area to a depth of 17m.

Within the flattened remains of the Caroni Rivers, the ex-diver said, lay parts of a small boiler, rumoured to be from an old steam trawler or tug. He thought this vessel had sunk while helping with salvage work on the tanker – but that a bronze deck-gun had been removed from it back in the 1960s, and sold for scrap.

The only armed trawler unaccounted for in Falmouth Bay was the St Ives – but she had reportedly sunk nearly two miles away.

Appeared in DIVER December 2018

THEN I HAD A MESSAGE from wreck-researcher Kevin Heath, asking what I knew about HMT St Ives. The name had emerged in the course of his researches, and he sent me two documents he had found, both relating to mine-sweeping in December 1916. I saw nothing new in them, apart from a mine having blown up 1½ miles SW by W of St Anthony Point.

A few days later, Kevin sent me UC17’s mine-laying chart of its mission just before the demise of the St Ives. It showed the position of two moored mines it had laid near Falmouth on 18 December, 1916, written on the map as “18 XII 16”.

I created an overlay of this chart on one of Falmouth Bay. The U-boat sketch was surprisingly accurate, and showed that the two mines had been laid around 100m from the Caroni Rivers’ location.

Re-reading the mine-sweeping logs, something suddenly jumped out at me. One document stated: “On 18 December one enemy mine was swept up and destroyed one mile east by south from Manacles Buoy. On 21 December, HMT

St Ives struck a mine 2 miles SSW of St Anthony Point. The commanding officer and 10 men were lost. Since this report a moored mine has been destroyed 1½ miles SW by W of St Anthony Point on 30 December. This was a five-horned mine having a horn in the centre of the top.”

So, “2 miles SSW of St Anthony Point”, not “WSW” as in the Commodore’s report to the Admiralty. This now put the trawler close to the Caroni Rivers.

The flattening of the Caroni Rivers would have been so violent that it would also have flattened anything near it – including whatever was left of the St Ives.

Over the years the Caroni Rivers has been dived thousands of times. I have dived it myself more than 20 times.

Now aware that within the wreckage are likely to be the remains of the St Ives and her crew, I’ll think of them and their sacrifice on future dives.

Any visiting divers will also be informed of the two intermingled wrecks, and the lives lost on the St Ives.

The St Ives struck a mine in 1916, the Caroni Rivers struck one in 1940 – 24 years apart, in separate wars but in the same location. It’s not uncommon for two wrecks to be found in the same place, especially a place such as Falmouth Bay, with its narrow shipping channel.

Where best to lay a moored mine in WW2? Probably the same place as it had been in WWI.

I HADN’T DIVED the Caroni Rivers since 2010, when another skipper had taken me out to the site. Looking through my photos I had dived two sections and seen these pieces of boiler, but whereabouts?

When I take divers out to the Caroni Rivers, I usually drop them on the section closest to shore, believed to be the bow. This covers a very large area of seabed, so it seemed the best place to start any new search for signs of the St Ives.

The Caroni Rivers lies at 21-25m, not ideal for a long searching dive on a single cylinder. I had invited Dr Dan Reynolds of Lungfish Dive Systems to join me for the dive, and he brought two of his closed-circuit rebreathers along to make the dive easier.

I dropped the shotline at the southern edge of the most inland piece of wreckage, so that when the tide started it would take us along the wreckage. Visibility wasn’t great.

An enormous circling school of bib surrounded us. A lobster hid under a piece of wreckage, not appreciating my bright new video light.

Several conger eels, for which the wreck is known, poked their heads out of pipes and pieces of wreckage. The other divers joined us, and we set off to cover as much ground as possible.

I remembered that the boiler had been close to the edge of the wreckage, but a vast amount of twisted and bent metal lay everywhere. We covered the eastern side, staying close to each other and in sight of the edge, and the open-circuit divers gradually broke away and headed up.

As we moved further north, the visibility worsened and we ran out of marine life and wreckage. We had spent 62 minutes searching the wreck, and had seen nothing out of place.

A FEW WEEKS LATER, Dan was in Devon and asked if I had any diving planned. I said I had a day free, and wanted to check out the western side of the Caroni Rivers.

This time we were closer to high tide, so a few metres deeper. We could drop the shot at the north end and let the tide take us south. I gathered the same group together, and we headed out.

I dropped the shot where Dan and I had finished the previous dive. Visibility was much as before, at 3-4m. The amount of marine life increased as we progressed, with more wrasse this time.

We noticed some very big pieces of netting that had been there a long time – it would take several large boats to retrieve such an amount. Once past the nets the visibility increased slightly, and I noticed a lot of wreckage I didn’t recognise from any of my previous dives.

By now only Dan and I were left, but after 67 minutes we ascended. We hadn’t run out of wreckage, just enthusiasm.

Perhaps I should try the other sections of the Caroni Rivers? I contacted Gary, the skipper who had taken me there in 2010.

I didn’t expect him to remember where he had dropped us, but it would be handy to compare his co-ordinates, and a few days later he sent me the numbers.

The following week, I had a few divers interested in a mid-week dive. My partner Ruth was on holiday and fancied a dive too. I told everyone what to look for as we were leaving port, and they all seemed quite excited about their mission.

As we approached the site, I thought I might look for more wreckage further south on my sounder.

There was another mark on the sounder: “Caroni 2”. I had recently replaced the instrument and reloaded my old dataset but I was sure Caroni 2 hadn’t been there before, so it must have been something I had previously deleted.

I slowly circled the waypoint. The sonar showed that there was wreckage there, so I dropped the shotline on the tallest piece.

The divers entered the water, and 40 minutes later Ruth’s DSMB hit the surface. I made a mental note of where it was, in relation to my shotline.

Ruth surfaced. I moved the boat over and she said: “I think I’ve found it.”

I collected the rest of the divers, then had a quick look at Ruth’s camera. The images looked promising.

I made my way to roughly where she had surfaced and marked the spot as “St Ives”, tempting fate.

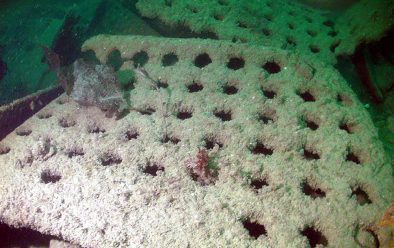

Back on shore, I reviewed Ruth’s photos and video-clips. They showed many rows of circular holes, as well as what looked like a firebox. I needed to check it out.

DAN BROUGHT THE REBREATHERS along the following week and we headed out to the new “St Ives” waypoint. We descended the 23m line, and towards the bottom could see that this part of the Caroni Rivers wreck looked more interesting, and offered better visibility.

We started to look around, watched

by conger eels and wrasse. Within a few metres of the shotline I saw what Ruth had seen – a couple of plates full of rows and rows of holes, with a circular cut-out.

The holes would be where the tubes inside the boilers connected, and the cut-out was the firebox into which coal would be shovelled.

They were definitely from a different vessel; made of a far thicker metal and even having a thicker concretion. Looking around, I saw a curved piece of metal that looked like a boiler’s outer casing.

I carried on circling the area, staying clear of some of the large congers. We saw the massive driveshaft of the Caroni Rivers, very close to the boiler parts.

There were also a few pieces of coal on the seabed, the only coal I had seen on or near the wrecks.

A school of bib circled as we covered the area once again, but there was no other visible evidence of the St Ives. We finished our dive after 71 minutes.

We had found what we were looking for, evidence of an older wreck where historical data said there should be one. There were no other lost wrecks in the area, and it would explain why the St Ives had never been found before.

Although it appears that the mystery of the St Ives might finally have been solved, it does leave one question.

What are those 12 cast-iron blocks WSW of St Anthony?