After a short run of deeper wrecks, here is a Belgian liner that is more widely accessible. It’s a popular Weymouth dive, says JOHN LIDDIARD. Illustration by MAX ELLIS

An old Weymouth favourite, the 5965-ton Belgian motor ship Alex Van Opstal, an early casualty of World War Two. It was sunk by a mine on 15 September, 1939, just 15 days after the German invasion of Poland.

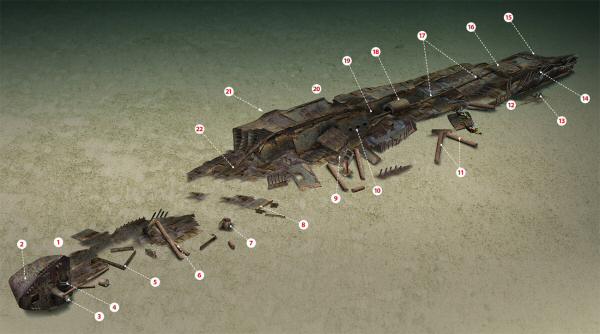

Charter-boats generally hook a shotline across the bow (1), tipped over almost 90° to port, so that the deck is close to vertical and the starboard side rises a good 5m from the 30m seabed.

This section is easily recognisable, so divers can begin the dive with some orientation, even if it does become a bit tricky later on.

Following down the starboard side of the bow, our route passes a pair of bollards, a reel of mooring cable and then a trio of smaller bollards that would have served as fairleads for mooring cable. The starboard anchor (2) is a modern stockless design, and is tight in to the hawse-pipe.

On the deck, the stub of a mast (3) stands between the holes for the opposite ends of the hawse-pipes, with the beam of a derrick resting across it.

Behind the mast is the anchor-winch (4). The wreck now breaks down to the seabed, leaving a few holes to explore inside the bow for those suitably experienced and prepared.

Following the wreckage aft, towards the deck side (the Portland or west side) of the wreck, the next main feature is the right-angle corner of the coaming from the forward hold (5).

Soon after this come a pair of bollards, and then a pair of masts lying on the seabed, with cargo-winches either side of their bases (6).

The forward of these two winches is intact but the second is broken.

Most of the masts on the Alex Van Opstal can be found in pairs, because they were fitted in a goalpost arrangement, side by side.

Here is where navigating this wreck becomes a bit tricky. There is a break where the mine exploded beneath the second hold, so any diver who just follows the edge of the wreckage will most likely keep turning left, and end up following the keel back to the bow.

The trick is to judge the line of the wreck, either from the lay of the deck or from the keel, and head out onto the seabed, following scraps of wreckage as you go. One notable item is a tubular mast-foot (7), upside-down and tipped in towards the wreck.

In good visibility, this is easy. In poor vis, divers could just as easily lose the wreck completely.

Within about 10m, the wreckage begins to pick up again, with hull- and deck-plates and some curved assemblies of 2in pipe (8) that I suspect were refrigeration machinery, either for galley supplies or a refrigerated hold.

The wreckage becomes denser as our route approaches the middle of the ship, with debris from the superstructure including another pair of masts and a windowed section of plate that may once have been part of the engine-room skylight and ventilator (9).

Just a little in from this, a section of hull-plate has a line of circular holes (10) where portholes were once fitted.

Little remains of the first hold aft, but the point between the aft holds is easily identified by another pair of masts (11).

The aft hold is similarly unrecognisable, and our route soon comes to the stern (12). Like the bow, this has fallen to port.

Unlike the bow, most of the upper deck has broken apart, with some debris including an easily recognisable pair of bollards (13) on the seabed.

The open ribs of the stern (14) form an impressive tunnel that can be followed the rest of the way aft.

Rounding the stern, the rudder (15) lies flat to the seabed and remains attached to the rudder-post. Inside the propeller cut-out, the propeller has been salvaged, but the tail-end of the shaft still protrudes from the stern gland.

The keel of the hull is initially intact (16) but soon breaks open. A little further on the propeller-shaft reappears (17), and can be followed all the way forwards through an arch of propshaft tunnel (18).

The wreckage then banks up over the shaft (19), presumably held up by the remains of the engine. A broken thrust bearing is just visible beneath the debris.

I once spent ages looking for the usual steam-engine machinery and boilers, only to find out later that the Alex Van Opstal was a motor ship, so had a diesel engine.

This section of the ship (20) is basically upright, but broken down to a lower deck, with most of the upper part of the wreck and superstructure fallen off the port side that we followed aft earlier on our tour.

Towards the forward and starboard side a split runs along it, through which a pump can be seen (21).

Across on the port side, a hull-plate (22) bridges between the lower part of the hull and the seabed to make a big triangular swim-through, but I would venture inside only in very good visibility.

The Alex Van Opstal is a big wreck. Even once you know your way around, it will take a good 30 minutes to complete this route. A drifting decompression will be necessary on a delayed SMB

EARLY WW2 VICTIM

KLAUS EWERTH TOOK U26 OUT OF WILHELMSHAVEN on 29 August 1939, four days before Britain declared war on Germany. By 10 September, this small Type-1A U-boat was off the Shambles bank, laying a minefield to catch ships in the approaches to Weymouth and Portland.

The first victim was the 5965-ton Belgian cargo and passenger liner Alex Van Opstal, providing a regular service between New York and Antwerp, to where it was returning.

Belgium was still neutral, but mines are indiscriminate. On board were a crew of 49 and eight passengers.

Captain Vital Delgoffe had received orders from the ship’s owners, Maritime Belge, to divert to Weymouth for inspection before continuing on the voyage. Sea conditions were rough, but surface visibility was good in the afternoon light.

Captain Delgoffe plotted a route past the east of the Shambles bank. By 5.55pm, having skirted the shallows, he had just ordered a change of course back towards Weymouth when a tremendous explosion beneath number 2 hold lifted the ship out of the water and broke its back forward of the bridge.

At 6.35pm, as the sea rose above the shelter-deck, Captain Delgoffe was the last to enter a lifeboat. The Greek steamship Atlanticos stopped nearby to pick up the crew and passengers. Amazingly, there were no fatalities.

The Alex Van Opstal sank soon after, falling across a cable and disabling a submarine detection loop, part of the harbour’s defence system.

U26 was by now well clear of the scene, 120 miles out into the Atlantic past the Fastnet lighthouse. Over the coming months the minefield went on to claim two further victims, the 6873-ton Dutch ship Binnendijk and the 4576-ton Greek steamship Elena R (Wreck Tour 123, December 2009), sunk respectively on 7 October and 22 November. Both are also popular dives from Weymouth and Portland.

TOUR GUIDE

GETTING THERE: For Weymouth, follow the A37 or A354 to Dorchester, then the A354 to Weymouth and on to Portland via Chesil Beach, turning left for the old Castletown dockyard as the road starts to climb the hill to Portland. Scimitar Diving is located at the Aqua Sport Hotel, on the left as you enter Castletown.

HOW TO FIND IT: The GPS co-ordinates are 50 32.437N, 002 16.133W (degrees, minutes and decimals). The wreck lies with its bow to just east of north.

TIDES: The Alex Van Opstal lies east of the Shambles Bank, with its complicated tides. The wreck should consequently be dived only 2.5 hours before high water Portland.

DIVING & AIR: Scimitar Diving Website, 07765 326728

ACCOMMODATION: Aqua Hotel Website, 01305 860269

LAUNCHING: Slips are available at Weymouth and Portland. Harbour and launch fees are payable.

QUALIFICATIONS: PADI Advanced Open Water or BSAC Sports Diver, though the wreck lies just a metre deeper than the PADI AOW limit at the stern. It’s a great depth for getting the best from nitrox.

FURTHER INFORMATION: Admiralty Chart 2610, Bill of Portland to Anvil Point. Ordnance Survey Map 194, Dorchester, Weymouth & Surrounding Area. Dive Dorset, by John & Vicki Hinchcliffe. Weymouth tourist information 01305 785747.

PROS: A big motor ship with lots of wreckage to explore.

CONS: If visibility is poor, getting between the forward and aft sections can be difficult.

DEPTH RANGE: 20m-35m