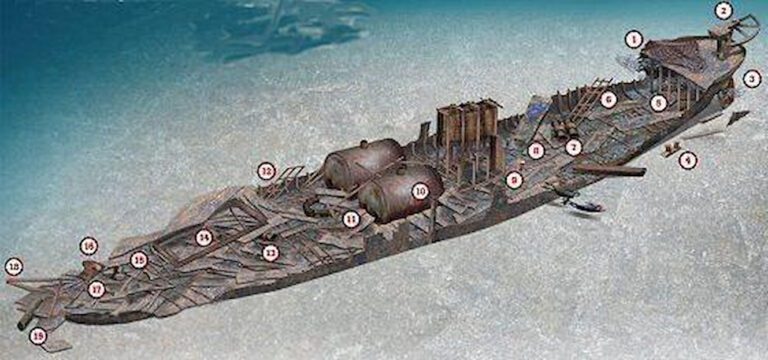

It’s a fair way out into the Irish Sea, but this 1890s steamship and U-boat victim still packed with equipment is well worth a look, says JOHN LIDDIARD. Illustration by MAX ELLIS

LOCATED SOME 18 NAUTICAL MILES east of south-east of the Isle of Man, and about 40 nautical miles north of Anglesey, the steamship Liverpool is one of our less-accessible wrecks, yet it is well worth the effort to get there.

On a flat 38m seabed, the parts that stick up most and show best on an echo-sounder are the boilers, the engine and the stern.

When I dived the wreck, the shotline was nicely hooked onto the starboard side of the stern, so that’s where our tour of the wreck will begin, at 32m (1). A trawl beam and net are draped over this side of the stern, though the net is old and easily visible, so presents no hazard.

The main feature of the stern is the rudder-post topped by the steering quadrant, standing several metres clear of the main deck (2) and covered in densely packed anemones, with a thick fur of hydroids on the outer ring of the steering quadrant.

There would originally have been another deck level, with the remains of a bearing near the top of the rudder-post, but this has collapsed and decayed, leaving little trace.

Dropping below the stern, the four-bladed iron propeller is still in place and the rudder is hard to port (3). Both are covered in a mixture of daisy and plumose anemones and surrounded by pouting. The general depth of the seabed is 38m, with a 2m scour below the stern.

Staying close to the seabed and moving forward along the port side of the wreck, the hull is broken and collapsed down until it is almost level with the seabed, alongside a pair of bollards (4).

Now moving back onto the wreck, a decayed bulkhead (5) supports the deck at the stern and provides a view inside, through the large shoals of pouting inhabiting the wreck.

The Liverpool was only a small steamer, 686 tons and 62m long with a beam of 9m, so in good visibility it is quite easy to progress forward along the centre-line of the ship, zigzagging to either side to investigate interesting items of wreckage.

First, towards the starboard side, is a section of railing (6), propped slightly above the wreckage and home to another fine collection of anemones.

Back on the centre-line of the wreck, but slightly askew, is a winch that would have served the aft holds, and its mounting plate (7). Just forward and to starboard of the winch is a steel plate with a collared ring at one end (8), perhaps displaced from above the engine. The collared ring would have been the base of a ventilator.

The triple-expansion engine (9) is a beautiful and intact example, showing the cylinder size increasing from the high-pressure cylinder at the front of the engine to the low-pressure cylinder at the stern, with the connecting rods and crankshaft exposed below.

Steam was provided by a pair of boilers (10), both resting in place forward of the engine.

Forward of the boilers on the centre-line of the ship, the steering engine (11) is a G-shaped block of machinery. Off to starboard, another section of railing (12) is most probably from one of the bridge wings.

The winch that would have served the forward holds (13) is again on the centre-line, though partly covered by a section of hold coaming (14).

Our tour is now in the area of the bow, though this is well broken, perhaps from when the Liverpool struck the mine in 1916, or when she went down by the bow some six hours later.

Closer to the centre-line still, a large capstan (15) has fallen to one side. The anchor-winch (16) is slightly off to starboard.

A large Admiralty-pattern anchor (17) is partly covered by a hull-plate across one fluke. A small derrick has fallen to starboard (18), the frame stretching off the wreck and held above the seabed. Then, to the port side of the bow, an anchor hawse-pipe rests (19).

Despite the depth, to end the dive a quick swim back to the stern will take only a couple of minutes.

The rudder-post is an ideal place to launch a delayed SMB, before drifting off through the shoal of pollack that patrol in the current above the stern.

A CHILD OF SORROW

The Liverpool, a 686 ton, 62m steel steamer, was built in the Liverpool yard of J Jones & Sons in 1892. Her owners, the Sligo Steam Navigation Company, registered her home port as Sligo in Ireland, then still part of the United Kingdom, writes Kendall McDonald.

She worked as a short-voyage general cargo-carrier, often steaming back and forth between her name port and home port. Her three-cylinder triple-expansion engine with two boilers could produce 187hp, so she was not fast, but she was reliable and profitable, and remained so for the next 22 years.

During all those monied years, the owners of the Liverpool probably gave less thought to the possibility of war with Germany than to that of home rule for Ireland. The outbreak of war in 1914 put a stop to that, and the Sligo Steam Navigation Company found its ships at war too.

Over the next two years, the cargoes in the holds of the Liverpool were more warlike, but the government money was good.

The German Navy had launched the first of its unterseeboote, the U-1, in 1906. Its submarine warfare developed in haphazard fashion, as it did not quite understand that it possessed a weapon capable of bringing Britain to its knees by sinking the merchant ships on which it relied for food and war supplies.

It was one of the much later versions of U-boat that was to curtail the Liverpool’s sea time. The U-80 was one of the big new minelayers, nicknamed by crews “the Children of Sorrow”.

She served in the 1st U-Boat Flotilla of the German High Seas Fleet, which was ordered to resume the sink-on-sight war against merchant shipping in October 1916.

U-80 carried out several missions around the Hebrides and in the Irish Sea. Commanded by Oberleutnant von Glasenapp, she laid a minefield off the Isle of Man, 11 miles south-east of Chicken Rock Lighthouse, on 18 December, 1916, to catch shipping using Liverpool.

It caught the Liverpool two days later. Three of the crew died in a huge explosion when she hit a contact mine. She sank swiftly, but the rest of her crew were saved.

After sinking 26 ships in her wartime career, U-80 was scrapped by Britain after the war.

TOUR GUIDE

GETTING THERE: Isle of Man – Ferry from Liverpool or Heysham to Douglas with the Isle of Man Steam Packet Company, 08705 523523. Anglesey – Quest picks up from the pontoon in front of the harbour office at Menai Bridge (the town, not the bridge itself).

TIDES: Slack water is essential and occurs one hour before low water and high water Liverpool.

HOW TO FIND IT: The GPS co-ordinates are 54 00.363N, 4 33.411W (degrees, minutes and decimals). The bow points to the south, with the highest points of the wreck being the boilers, engine and stern.

DIVING & AIR: From Port St Mary, Isle of Man – Mike Keggen, Isle of Man Diving Holidays, 01624 833133, From Anglesey – Scott Waterman, Quest Diving Charters. 01248 716923, email.

LAUNCHING : Slip at Port St Mary.

ACCOMMODATION: Isle of Man – Self-catering flat above the dive-centre. Anglesey – B&B in the pub by the harbour office.

QUALIFICATIONS: Best suited to experienced divers prepared to do some decompression.

FURTHER INFORMATION: Admiralty Chart 2094, Kirkcudbright to Mull of Galloway and Isle of Man. Ordnance Survey Map 95, The Isle of Man. Isle of Man Tourist Information 01624 686766. Ordnance Survey Map 114, Anglesey. Shipwreck Index of the British Isles Vol 5, West Coast & Wales, by Richard & Bridget Larn.

PROS: A pretty wreck with lots of exposed machinery.

CONS: A long way offshore, so requires very good sea conditions.

Thanks to Mike Keggen and Scott Waterman.

Appeared in Diver August 2005