This is a centenary Wreck Tour, because we publish it 100 years to the day since the steamer King Cadwallon sank off the Scilly Isles. JOHN LIDDIARD reports, MAX ELLIS draws.

A DIVE ON THE KING CADWALLON usually begins on Hard Lewis Rocks, jumping in to 15-20m depth on the north side of their eastmost point, marked on the chart as “Dries 3.1m“’”. Photographs can be seen showing the King Cadwallon aground on the rock. As it broke up, the wreck simply slid sideways down the slope from where the photo shows it.

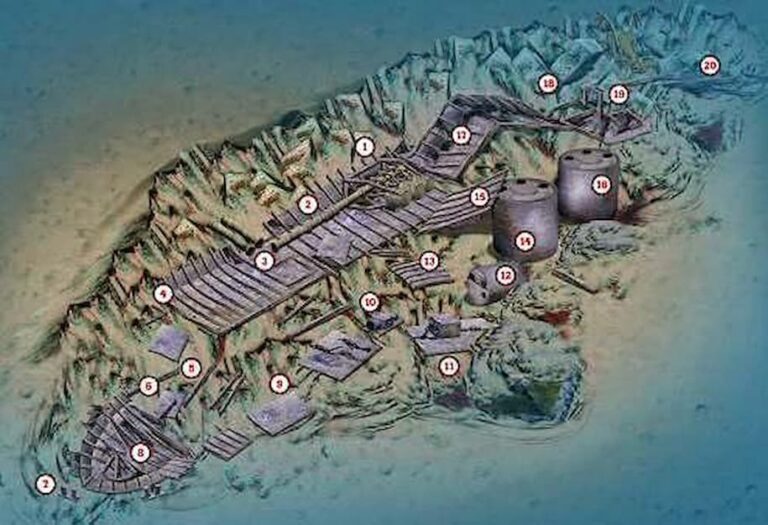

Following the slope down and north to 25m should soon lead to the wreck at the triple-expansion engine (1). This is enclosed in a tall frame and has fallen onto its starboard side, with pistons, connecting rods and crankshaft bearings mostly remaining intact.

Following the propeller-shaft aft, the thrust-bearing has been broken open to salvage the white metal, leaving only a series of square-section thrust-rings on the shaft (2).

The shaft continues aft for a couple of sections before it breaks, with, somewhat peculiarly, the last two sections resting side by side, sticking out at 90° to the port side of the wreck (3).

The ribs of the hull continue aft, slowly descending until the wreck breaks at 28m (4). Here, the shelf of rock that was supporting the hull steps away, leaving the unsupported stern to break off into deeper water.

Scraps of wreckage continue down the step (5), with the propshaft resuming where it enters the remains of the stern (6). The stern itself has fallen to starboard and aft. The wreckage fizzles out at 48m, where pairs of mooring bollards rest upright on the seabed (7).

The rudder-post has pushed upwards through the hull to leave the steering quadrant exposed a metre or two above the rest of the wreckage (8). Standing in the current, it is covered in white and orange plumose anemones.

Following the north edge of the wreckage back up the slope (9) reveals that, not surprisingly, much of the interesting equipment from the King Cadwallon has rolled off the starboard side of the wreck into slightly deeper water at around 33m.

A cargo-winch (10) marks a line that, if followed back to the wreck, would separate the two aft holds.

The 3275-ton King Cadwallon was carrying more than 5,000 tons of coal when it ran aground, although there are no signs of it now.

No doubt the enterprising islanders acquired some to heat their homes through the next winter, but I suspect that most of it has simply been dispersed by storms over the past 100 years.

Just forward and out from the cargo-winch, nestled against some larger rocks, is a block of auxiliary machinery with a chain fed through it (11), possibly a steering engine, because it is too small for an anchor-chain on a ship of this size.

The steering-engine would normally be found right at the front of the superstructure, either in or below the wheelhouse. The location on the wreck-site is aft of the boilers, suggesting that the wreck broke up in stages, the steering-engine breaking loose before the hull was broken and the boilers rolled out. The donkey-boiler (12) is just forward of the steering-engine.

An upside-down deck-plate nearby hides another pair of mooring bollards (13) that could have come from the forward or aft end of the superstructure.

The larger main boilers have also rolled clear of the wreck and stand on end, fire-holes uppermost. The first boiler (14) has a section of hull or deck resting against it (15) to leave a nice swim-through beneath the two to the second main boiler (16).

Rejoining the main part of the wreck just forward of the engine, the line of the keel is broken and skewed in more than one place as the hull crosses a ridge of rocks (17).

The line of the wreck becomes awkward to follow, especially because some very square and regular blocks of granite covered in anemones stand almost in line with where the wreckage would be expected to continue (18).

The last significant piece of wreckage is a section of hull with frames from a bulkhead just off to starboard (19).

The location on the overall line of the wreck suggests that this could have been the bulkhead between the forward hold and the bow.

As the rocks shallow to 20m, there are still occasional scraps of wreckage (20), but nothing significant, though the anchor-winch, chain, hawse-pipes and bollards from the bow must be somewhere. Perhaps they broke to the other side of Hard Lewis Rocks before the bulk of the King Cadwallon broke and slid back to its current location.

Provided there is not too much surge, any decompression can be comfortably seen off while playing around in the shallow rocks of Hard Lewis above the wreck. There are plenty of small sections of wall cracks and gullies hidden beneath the kelp.

When the time comes to surface, however, it is best to swim clear of the rocks, so that the boat has room to pick you up.

A FOGGY FATE

FOG WAS, IS, AND ALWAYS WILL BE, the curse of sailors around the Isles of Scilly. It has a nasty habit of coming down suddenly there, lifting as suddenly, then fast clamping down again, writes Kendall McDonald.

Many of the wrecks around these islands owe their underwater existence to fog. King Cadwallon is a prime example. She was a 3,275-ton steamer of Glasgow’s King Line, 99m long with a beam of 15m and a draught of 7m. Six years old in 1906, the vessel had twin boilers and a three-cylinder triple-expansion engine that gave her 278hp.

With Captain Joe Mowat on the bridge and 27 crew busy aboard, at 8am on 21 July, 1906 she steamed out of Barry Docks for Naples. In her holds she carried 5,043 tons of Welsh coal.

Despite a southerly breeze, the King Cadwallon made her way down the Bristol Channel in a thickening haze. Off Lundy the fog lifted, giving the captain just time to fix his position before it clamped down thicker than before.

From then on, the captain and crew saw nothing but fog. When they thought they were near the Scilly Isles, they started taking soundings every few minutes. All casts of the lead signalled that they were in very deep water.

In the darkness at 5am on 22 July, the lead told them that they were over 27 fathoms (50m). Three minutes later the King struck the highest point of Hard Lewis, one of the reefs of the Eastern Rocks of the Scilly Isles. Hard Lewis, parts of which thrust up from a 50m seabed, has seen at least six wreckings.

King Cadwallon’s engine was stopped immediately – just as the fog disappeared. Within 10 minutes the forehold was full of coal-black water. As the vessel began listing to starboard, the captain and crew took to the boats with their belongings, and floated on the calm sea until help arrived.

Shortly afterwards the King Cadwallon slipped back off the rocks and sank, more or less upright, into deep water.

TOUR GUIDE

GETTING THERE: The Scillonian sails daily from Penzance, 01736 334220, or fly from Land’s End with Skybus, 08457 105555, or by helicopter from Penzance, 01736 363871. For a group with diving kit, a freight container can be booked for the Scillonian.

TIDES: Slack water is essential and occurs at low water St Mary’s.

HOW TO FIND IT: The King Cadwallon lies against the north side of Hard Lewis Rocks. GPS co-ordinates are 49 57.960N, 6 14.610W (degrees, minutes and decimals). Don’t bother looking for an echo, just find 15-20m depth to the north of the rock and then swim down the slope.

DIVING, AIR & ACCOMMODATION : St Martin’s Diving Services, 01720 422848, Scily Diving.

QUALIFICATIONS: Variation in depth makes this wreck suitable for divers wanting to build up their depth experience without committing to a rectangular-profile dive.

LAUNCHING: It’s a long way from the slip at Penzance, but the journey is feasible for a large RIB in good sea conditions, especially if the divers take the ferry.

FURTHER INFORMATION: Admiralty Chart 34, Isles of Scilly, St Mary’s Road. Ordnance Survey Explorer Map 101, Isles of Scilly. Dive the Isles of Scilly and North Cornwall, by Richard Larn & David McBride. Shipwrecks Around the Isles of Scilly, Gibsons of Scilly. Isles of Scilly Tourist Information.

PROS: Wrecked among excellent surroundings, this is a good wreck for scenic divers who dabble in wrecks, but there is also plenty for the dedicated wreckie to explore.

CONS: You must at least bounce deep to get the most from this wreck.

Thanks to Jo and Tim Alsop.

Appeared in DIVER August 2006

Other Scilly Isles Wreck Tours on Divernet: Hathor & Plympton