A ride out from Littlehampton, it’s the engineering that makes this china-clay-carrying steamer so distinctive, says JOHN LIDDIARD. Illustration by MAX ELLIS

LOOK AT STEAM CARGO SHIPS over the 60 years from 1890 or so, and there is usually little variation in the general design. It’s the detail that makes them different and interesting. In the case of the Zaanstroom, it is the cargo-handling equipment and “spare wheel”, but more of that later.

As on most wrecks of this size (66m long) and depth (deck at 25m, seabed at 29m), our tour begins in the middle (1), where the wreck is most intact. The boiler is below deck level, tilted up at the forward end (2).

Dropping down in front of the boiler, the hold is about half-full of chunks of china clay, banked up towards the boiler (3). Brush away the silt and they are given away by their grey-white colour.

I wonder if any diving potter has salvaged some of the china clay and created a pot with it? How about a china model of the ship? (All done legally via the Receiver of Wreck, of course.) Though china is an obvious use, china clay is actually used in all sorts of products, from tyres to paper to cosmetics.

Just a little way forwards, the main deck has collapsed and the upper plates of the hull have rotted through to leave a picket fence of closely spaced ribs. Fallen onto the piles of clay on either side of the hold are cargo-handling cranes (4).

A stalk that used to run down to the keel supports a rotating base that would have been at main-deck level. Above the rotating base is the body of the crane, although no sign of the associated cables and jibs remains.

The fitting of the cranes most likely reflects the owners, the Holland Steamship Company, specifying a ship for short journeys. The rapid loading and unloading of bulk cargo would have a significant impact on profitability.

In such use, lots of small cranes along the sides of the ship have a speed advantage over masts and derricks, especially where dockside equipment is not available to help.

Continuing towards the bow, either there never was a bulkhead between the forward two holds or it has completely decayed. All that remains are a few uprights that would have supported the main deck, with a section of mast fallen between them.

Next in the forward hold is more china clay and another pair of the cargo-handling cranes (5). It looks as if each hold was serviced by a pair of such cranes, one each side of the ship.

The deck at the bow has fallen slightly back and to port (6) as the supporting hull has decayed. The original height of the deck can be observed from the ribs protruding upwards on the starboard side of the bow.

On the deck, the anchor-winch and the starboard pair of mooring bollards are still firmly in place (7). The corresponding bollards on the port side are missing, presumably dropped to the seabed and buried beneath the sand.

Below the deck, the sides of the bow have rotted through between the ribs, though the ribs are too close together for a diver to swim through (8).

Now heading aft along the port side of the wreck, streaks of grey-white on the seabed are china clay that has washed out of the holds.

Looking at the actual level of clay chunks in the forward holds, I don’t think much of it has actually washed away. While china-clay mining uses high-pressure water jets to extract a slurry, it isn’t soluble.

Sea water and wave action would erode the clay only at the same rate as it would erode any other clay-based rock. As a rock, china clay is quite a dense cargo, so I expect the holds were only half-full by volume when Zaanstroom was fully loaded by weight.

Drawing level with amidships, sections of rib and plate on the seabed mark the remains of the superstructure (9). Back on deck, aft of the boiler the location of the wheelhouse is marked

by the steering engine (10), closely followed by the top of a three-cylinder triple-expansion engine poking up through the wreckage (11).

To either side, small hatches are the loading hatches for the fuel bunkers, located in a saddle configuration to either side of the engine.

The aft holds (12) are again piled with chunks of china clay. Somewhere beneath the cargo is the propeller-shaft tunnel. It was a growing leak here that resulted in the Zaanstroom foundering on 21 December, 1911.

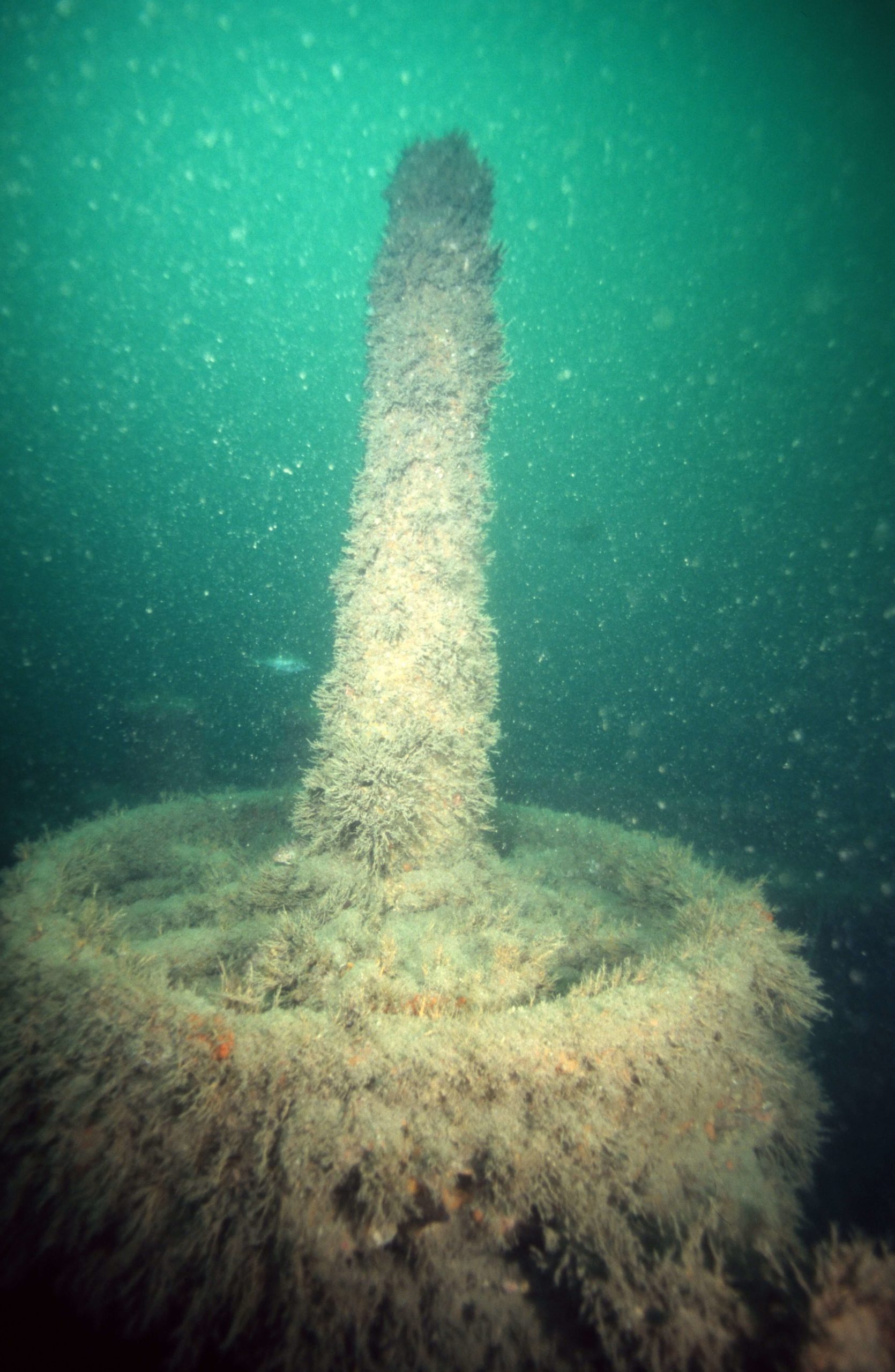

The sides of the hull reach up to deck level, but between the ribs the hull-plates are actually rotted through further down to the seabed. There is only one pair of the cargo-handling cranes serving the aft holds (13). Both cranes have fallen on top of the cargo with the hold-coamings, but the base for the port crane is still upright and secured in place.

Right at the back of the hold is a spare propeller, fallen upright against the bulkhead (14), from where it once would have been stowed on the deck above. The location would have been next to the spare section of propeller-shaft that is still secured to the port side of the stern deck (15).

Over the side of the stern and down on the seabed again, Zaanstroom‘s propeller is mostly buried in the sand. Only one blade sticks up vertically (16). The rudder and steering have broken loose and fallen to port, with the steering quadrant held clear of the seabed (17).

Finally, back on deck, just forward of the rudder-post is a ladder secured to the deck (18), and next to that an enormous ring-spanner (19).

With all these parts and tools for handling broken shafts and propellers, it is almost as if the problem was handled as casually as changing a wheel on a car.

Considering that the cause of the Zaanstroom‘s loss was water flooding in through the propeller-shaft tunnel, however, perhaps the tools and parts were a wise precaution.

TOUR GUIDE

GETTING THERE: Boats are berthed on the pontoon where the riverside road meets the seafront road, by the Nelson Hotel in Littlehampton.

TIDES: Visibility is best at low-water slack, six hours after high water Littlehampton.

HOW TO FIND IT: The GPS co-ordinates are 50 39.148N 000 36.920W (degrees, minutes and decimals). The bow points to the east.

DIVING: Our Joy, skippers Vernon and Daniel Parker, 01243 553977.

AIR: Arun Nautique, 01903 730558. Ocean View Diving Services (also nitrox and trimix).

ACCOMMODATION: B&B at the Nelson Hotel, Littlehampton, conveniently located next to the charter-boat pontoon, 01903 713358.

QUALIFICATIONS: Ideally suited for the average spread of qualifications on a club trip.

launching: Closest slip is at Littlehampton.

FURTHER INFORMATION: Harbourmaster, 01903 721215. Admiralty Chart 1652, Selsey Bill to Beachy Head. Ordnance Survey Map 197, Chichester & the South Downs, Bognor Regis and Arundel. Dive Sussex, by Kendall McDonald. Shipwreck Index of the British Isles Vol 2, by Richard & Bridget Larn. Mole Valley SAC.

PROS: Interesting engineering and well worth a look. It’s also a good alternative if the nearby Northcoates is busy with other dive-boats.

CONS: At low water you have to wait for the tide to ride before you can get back into the harbour.

SWELLING UP INSIDE

When you are carrying a full cargo of china clay, it is best not to spring a leak. That’s an obvious understatement, but one with which Captain Paul Ralishock certainly agreed after being rescued with his crew from the 899-ton coaster Zaanstroom.

She sank at 7.45pm in the early darkness of 21 December, 1911, writes Kendall McDonald.

Captain Ralishock’s cargo was china clay,and he was on his way home from Fowey to Amsterdam. He sprang his leak close to the stern and very near the propeller-shaft housing soon after leaving Fowey, although he was not aware of the clay swelling with sea water until hours later, when the wallowing became obvious.

The Zaanstroom was built by Huygens and Van Gelder in Amsterdam in 1895, 66m long with a beam of 310m and a draught of 5m. Her three-cylinder triple-expansion engine produced 108hp from two boilers. She was worked hard by her owner, Hollandsche Stoomb Maats of Amsterdam, and produced good profits from the money it had spent on her building.

When it became obvious, just after 7pm, that the Zaanstroom would soon sink, the coaster was two-and-a-half miles ENE of the Owers Light Vessel. Captain Ralishock ordered his crew of 20 to the boats and the vessel foundered soon after they pulled clear.

They were picked up by the steamer Westdale of Liverpool and landed at Ryde. But somehow in the darkness and confusion of the rescue, one of the crew was lost – the only casualty.

Newham Sub-Aqua Club owns the wreck, which the club’s divers positively identified when they recovered the bell in 1980.

Thanks to Vernon and Daniel Parker, Paul Walkey, Tim Walsh and Mole Valley SAC.

Appeared in DIVER October 2006

Also on Divernet: Ramsgarth