Imogen Manins heads to a popular Victoria pier dive site in Warn Marin/ Western Port Bay, Bunurong Country -a true hotspot for the elusive weedy seadragon.

Why Flinders Pier Is Famous for Weedy Seadragons

Melbourne offers first-rate wall, reef, and wreck dives -both within Naarm/Port Phillip Bay and beyond the heads. But it’s at the shallow piers that many divers and photographers cut their teeth and learn to appreciate the rich marine life that finds haven here in these cold southern waters.

On the eastern side of the Mornington Peninsula, you’ll get your fill of octopus and seahorses at Rye, nudibranchs at Blairgowrie, and, if you’re lucky, weedy seadragons at Portsea. But if you haven’t dived Flinders Pier, you haven’t been to the weedy seadragon capital of the world – and you’re in for a treat.

The town is exposed to water on two sides – Bass Strait to the south and Warn Marin/Western Port Bay to the west. Farmland borders the north and east, leaving Flinders feeling relatively isolated, though it remains technically within metropolitan Melbourne.

Flinders Pier History and Restoration Plans

Built originally in the 1850s-1860s alongside the town, Flinders Pier is much loved by locals, divers, fishers, and tourists. The pier itself points due west into Western Port Bay, buffered only slightly from direct southerly winds by West Head – home to the Royal Australian Navy’s West Head Gunnery Range. A contradiction to the peaceful views over the cliffs, machine gun fire rings out weekly from this otherwise tranquil setting.

Like many piers in Victoria, much of the pier has reached the end of its lifespan with various sections having been removed, rebuilt and remodeled over the decades. In its current form the first 180 metres of the original timber pier is severely deteriorated and has been closed for several years. The ‘Save Flinders Pier’ campaign has fought to ensure this historic section – running beside a still-accessible concrete length – is restored rather than demolished. After years of environmental and engineering studies, a new Heritage Victoria listing, and a funding agreement, Parks Victoria has now confirmed that permitted restoration work will begin in late-2025.

Diving Conditions at Flinders Pier

Melbourne divers are lucky to have an almost circular bay that offers diveable options regardless of wind direction. On the Port Phillip side, the southern piers are popular in southerly winds. Flinders, however, is best in north-westerlies with minimal swell. But here’s the catch – even when the forecast is flawless on paper, Flinders is infamous for defying expectations. Many expressive ‘F’ words have been used to describe its temperament – but for civility’s sake, let’s just call it ‘fickle’. You might arrive to find everything perfect, only to gape down from the pier and discover a disappointing arm’s length of visibility. But when Flinders is good, it’s truly exceptional – and we keep chasing the thrill of that perfect day.

Marine Life at Flinders Pier

The biosphere of Warn Marin/Western Port Bay is markedly different from that of Naarm/Port Phillip, with its own unique intertidal habitats and mix of marine, plant, and bird life. This may be part of what makes the site so unpredictable. The pier begins over fine sand, and as the water deepens, two keystone plant species – Zostera nigricaulis and Amphibolis antarctica -dominate the seabed.

Did you know?

Although they appear to be seaweed when drifting in the water column almost motionless, weedy seadragons are actually bony fish. They are related to seahorses, pipefish, and seamoths. The best time to see them is August-March.

Their glossy leaves are punctuated by crayweed, kelp, and sargassum, forming habitat ideal for our charismatic seadragons and the many other creatures gliding through. Flinders is an easy self-guided dive for all levels. It’s around 30 minutes from the nearest dive shops, so come prepared with full tanks, all your gear, and a back-up site if the vis is… well, fickle. Free parking, toilets, and picnic tables are just 80 metres from the pier. Most divers walk the 180 metres down to the lower landing for an easy entry – bring a trolley if you’re carrying heavy gear. A shore entry is also possible and is the best exit option at low tide, as the landing lacks a ladder. The typical route is simply to follow the pier directly out into Warn Marin/Western Port Bay and back with possible short deviations out into open water (being careful to avoid numerous fisher’s lines) if enticed by particular critter sightings. The seagrass remains thick under most of the structure, with sandy patches around the bases of pilings. The habitat is fairly consistent for the first 50 metres, but take it slow – seaweeds, tunicates, and sponges coat every piling, each one a microhabitat for hidden life.

At the end of the pier, you’ll find an old engine block and remnants of wreck structure now blanketed in plant life and buzzing with fish. The entire dive is shallow, with a maximum depth of 4.5m at the end of the pier enabling long dive times if the cold water doesn’t send you to shore sooner than your air consumption. Drop in from the landing and you might spot your first seadragon almost immediately. They’re masters of camouflage, and it may take time to tune your eyes to their drifting silhouettes and leaf-like appendages among the weeds.

I’ll never forget my first encounter, diving on breath-hold to take photos of a Shaw’s cowfish I spotted from the surface that really didn’t feel like posing for my camera. Nearing the end of my breath and with several typical unflattering shots of the cowfish’s tail, another creature glided into my peripheral vision. My heart thudded as my brain caught up – what initially looked like seaweed was something far more magical. In that instant, I was besotted. I was watching a weedy seadragon. Since that moment, I’ve been hooked.

My heart thudded as my brain caught up – what initially looked like seaweed was something far more magical. In that instant, I was besotted. I was watching a weedy seadragon

Did you know?

You can upload your weedy seadragon photographs to the SeaDragonSearch citizen science project. The project seeks photographic submissions to identify and track individuals for abundance and distribution research. It can be extremely satisfying and highly addictive to be involved in.

Underwater Photography at Flinders Pier

Weedy seadragons are slow-moving fish, so once you spot one there’s no rush, even if you are on breath-hold rather than scuba. Photographers will find that some individuals are very relaxed and focused on their feeding, enabling you to get quite close and frame a photo. Others will want nothing to do with you, using their impressive tiny purring fins to steer with great dexterity and relatively speed away over the seagrass.

There are many benthic fish here, and Shaw’s cowfish are more numerous here than anywhere else I’ve dived. They bustle about in small groups, nibbling along the sea floor with young bluethroat wrasse, goatfish, magpie perch, and clouds of mysids – the tiny crustaceans weedy seadragons dine on.

I usually shoot close-focus wide angle here with a fisheye lens and dual strobes. This set-up handles less-than-ideal vis well and rewards patient photographers who can stay neutrally buoyant in 2m–5m of water. The sunlight at either end of the day looks magical as it beams through the water and onto the thick green plants below. Macro also works beautifully – especially on the pier’s pilings and seabed, home to smaller treasures.

In this corner of the Great Southern Reef, the male weedy seadragons are first seen carrying their broods of glistening berry eggs in September, but you’ll find them in good numbers anytime between August and March. It is delightfully rewarding when swimming along, a brooding male weedy seadragon catches your eye and indifferently plays the posing game, drifting just above the seagrass with the sun behind. A few months later, the game changes – now you’re searching for tiny juveniles. It’s more challenging at Flinders than at Portsea due to the dense grass, but worth the search.

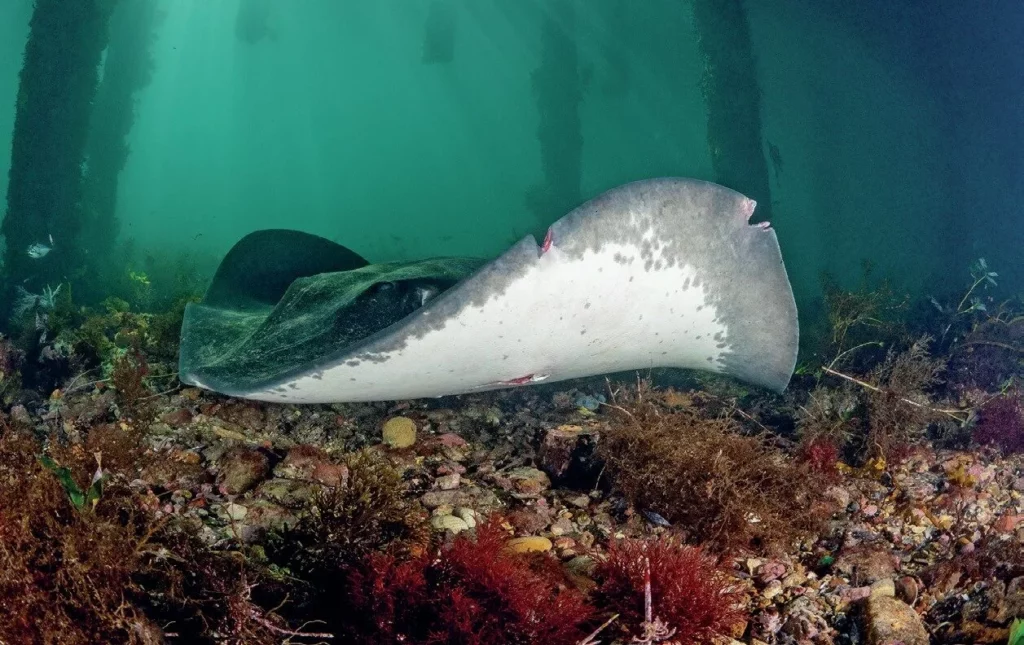

The smooth stingrays make for a fantastic subject too.

Nothing gets the heart racing quite like these huge shadowy creatures – as big as a king-sized quilt and weighing around 300kg – gliding past within arm’s reach. These are the largest residents of these waters, and several patrol the area, delighting and startling summer swimmers as they prepare to jump, squealing, from the pier and spot the massive dark form passing close by.

Some rays show signs of having had their own encounters with humans, hooks in the mouth or rips and tears in their magnificent fins. At least one local resident ray is even less lucky, having had its tail cut off in what I can only assume was a violent encounter with a fisher (rays are protected in Victoria within 400 metres of piers). Thankfully, most seem unbothered by respectful divers who can also enjoy watching small schools of silver trevally riding in formation at their snout.

It unfurled its vast, flexible web like a parachute, demonstrating a masterclass in texture and colour change, engulfing its prey before slowly retreating to its regular form

One day, as I finned slowly toward shore, a group of divers powered past me at top speed. I lingered, scanning the pilings – and was rewarded with a giant Maori octopus pouncing upon prey on a piling. It unfurled its vast, flexible web like a parachute, demonstrating a masterclass in texture and colour change, engulfing its prey before slowly retreating to its regular form. I moved closer, hoping not to disturb it with my flash. Eventually, it moved around the piling and slinked off into thick seagrass, leaving only its horned eyes periscoping above the leaves, watching me curiously. It’s encounters like these that make me wonder how many marvels I’ve swum past, oblivious. Many other visitors make a dive here special – draughtboard sharks, Melbourne skates, seals, and even dolphins.

If you have the opportunity to dive here and conditions stay good into the evening, I’d highly recommend a night dive. I’m struck by the abundance of anemones seemingly absent during the day – at night, wide open and feeding – glowing in vivid pinks, purples, oranges and reds like flowers of the night. Among them, the weedy seadragons hover almost motionless in the seagrass, their usual drifting replaced by a quiet stillness.

It’s the kind of scene that stays with you long after you’ve surfaced. It’s the quiet moments, the rare days when light pours through clear water, and the chance encounters with creatures you never expected that pull me back to Flinders again and again.

Frequently Asked Questions

Where is Flinders Pier located?

Flinders Pier is on the eastern side of the Mornington Peninsula in Warn Marin/Western Port Bay, Victoria, Australia.

Why is Flinders Pier famous with divers?

It’s considered one of the best places in the world to reliably see weedy seadragons in shallow water.

What marine life can be seen at Flinders Pier?

Divers regularly encounter weedy seadragons, Shaw’s cowfish, smooth stingrays, giant Maori octopus, nudibranchs and benthic reef fish.

What are the best conditions for diving Flinders Pier?

The site is best in north-westerly winds with minimal swell, though visibility can be unpredictable.

When is the best time to see weedy seadragons at Flinders Pier?

Weedy seadragons are most commonly seen from August to March, with brooding males visible from September.

This article was originally published in Scuba Diver Magazine

Subscribe today with promo code DIVE1 — enjoy 12 months for just £1!