Fragile comb jellies disintegrate when they are removed from the sea, but by analysing them by means of underwater photography and videography researchers have been able to identify new types off both Colombia’s Caribbean and Pacific coasts – including six species never before recorded in the country’s waters. All are featured in a just-published study.

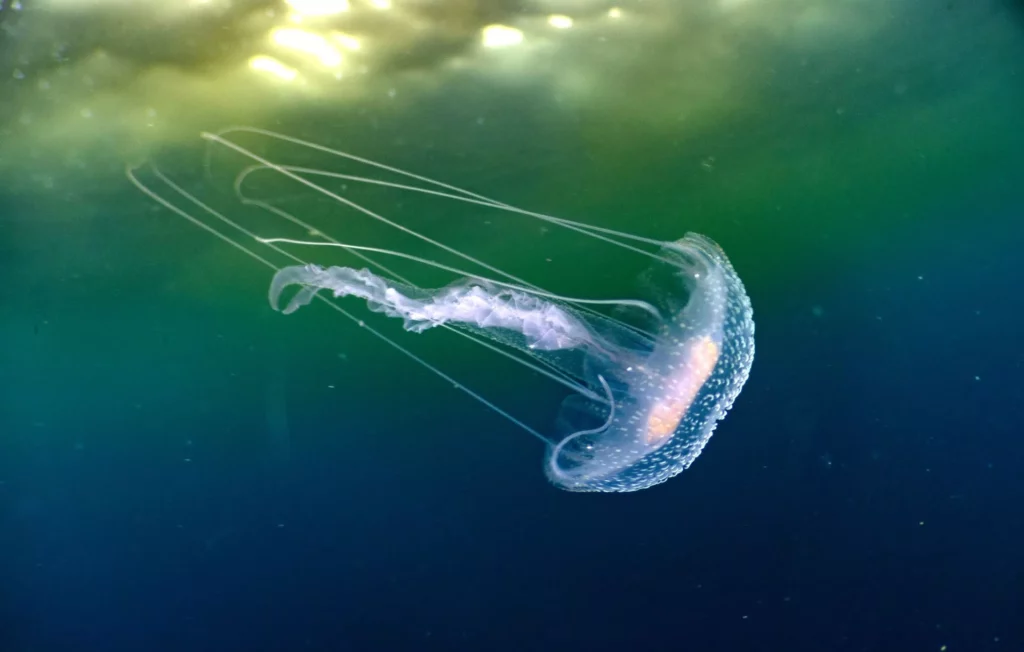

Comb jellies or ctenophores, a group of gelatinous plankton even older than sponges, dwell worldwide from shallow coastal waters to the deepest trenches and are also known as sea gooseberries, sea walnuts and Venus’s girdles.

Voracious predators, ctenophores’ diet consists of zooplankton, larvae, fish-eggs and other creatures. In turn they are preyed on by turtles, crustaceans and others, making them an important part of the food web.

Ctenophores’ bodies are propelled by rows of cilia that scatter light as they move. Most are bioluminescent, emitting blue/green or even red light that makes them stand out in the darkness of the deep ocean.

Despite having existed for millions of years, much detail about the diversity and distribution of these fragile 95%-water creatures remains unknown.

Most of the photographic and videographic material underlying the study was collected on a 2022 National Geographic Pristine Seas expedition in Colombia’s offshore Pacific waters. Additional records were provided through citizen-science observations in the Caribbean. Pristine Seas’ Colombian partners at the Marine & Coastal Research Institute (INVEMAR) led the research.

“The results fill a historical information gap on a key group of gelatinous plankton and demonstrate the value of non-invasive methodologies and explorations in remote areas to strengthen knowledge of marine biodiversity,” said lead author INVEMAR researcher Cristina Cedeño-Posso.

“This paper beautifully illustrates what happens when scientific rigour meets the art of underwater photography,” adds Pristine Seas marine scientist Juan Mayorga, a co-author of the study.

“These fragile organisms dissolve when collected in nets, so they can only be studied through images. Our team’s photography didn’t just document beauty; it enabled taxonomy and discovery, resulting in six new species records for Colombia.”

The study has just been published in Spanish in Revista de la Academia Colombiana de Ciencias Exactas, Físicas y Naturales.

Also on Divernet: 5 jellyfish species you may see more often in UK’s warming seas

Given that presumably as a predator, stealth is a great attribute and their place close to the bottom of the food chain, is there any theory as to why they display colours that make them stand out? It would not, on the face of it make much evolutionary sense.