- 1) His first dives on each sunken casualty of the bitter WW1 Gallipoli campaign were true journeys of discovery, and they can be for you too – Turkish diver MAHMUT SUNER has put together for Divernet a guide to shipwrecks around the peninsula he recommends for both recreational and technical divers

- 2) Ill-conceived action

- 3) Three groups of wrecks

- 4) Lighters

- 5) HMT Lundy

- 6) HMS Louis

- 7) HMS Majestic

- 8) HMS Triumph

- 9) Chartage

- 10) HMS E-14

- 11) Continuous currents

His first dives on each sunken casualty of the bitter WW1 Gallipoli campaign were true journeys of discovery, and they can be for you too – Turkish diver MAHMUT SUNER has put together for Divernet a guide to shipwrecks around the peninsula he recommends for both recreational and technical divers

One quiet Aegean morning, fisherman Nami cast off his small fishing boat and away we went, heading for the WW1 wreck-site of HMS Majestic.

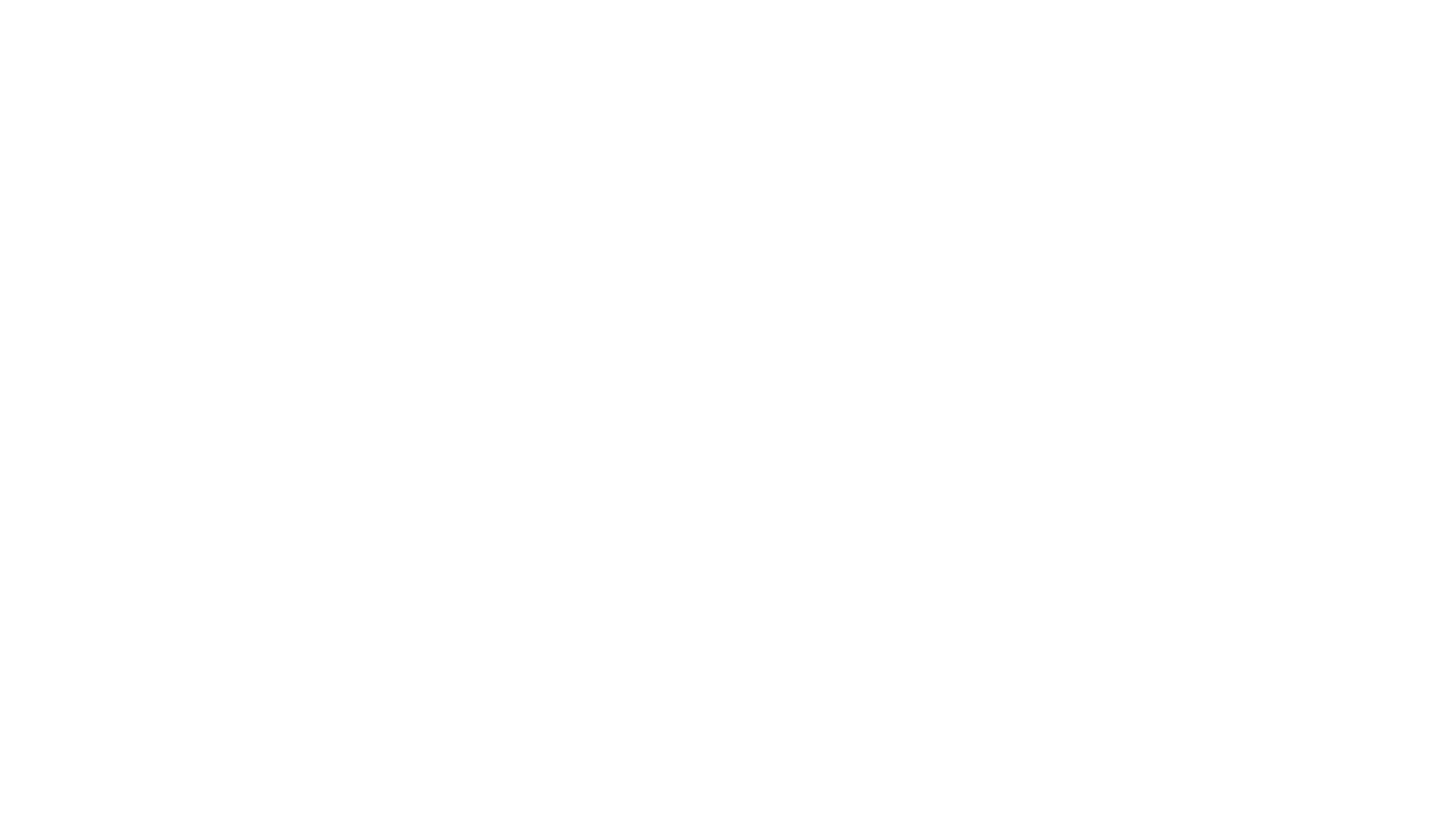

She was a tired old Royal Navy Dreadnought, built in 1906. This was to be my first dive on a great ship, and it made me feel sad that 49 sailors had been lost when Majestic went down.

For the first few metres of the dive visibility was not very good, and the water was cool. At 20m, the vis suddenly improved. A dark silhouette was now growing bigger beneath me with every breath I took.

I landed on the ship, but didn’t know which part I was on. I was the only diver there at that moment, and it was a lonely feeling. The wreck was immense, and I was sure that this was indeed HMS Majestic.

It was not easy to locate the area where she had been torpedoed by the U-boat U-21, but the deck was a mess. We could identify a 5in gun-turret bay, lots of ammunition, Enfield rifles, many bayonets, spanners for use in the artillery bay and live shells spread everywhere.

The portholes were lying on the sand to starboard. The wreck rested on an even keel, and amidships we discovered part of the captain’s bridge and observation tower.

On the way up I saw many medicine bottles and plates partially buried in the sand. This wreck was a time capsule from 1915, from a war of the brave.

Ill-conceived action

The WW1 campaign to force a passage through Turkey’s Dardanelles Strait was intended to enable the Allies to bolster Russia – the traditional enemy of the Turks – in its fight against Germany.

The Royal Navy embarked on an ill-conceived action. Its guns outranged the Turkish land batteries at the narrows of the strait, but its mighty fleet of 63 Dreadnought-class battleships, named for their supposed invulnerability and supported by 180 other vessels, proved no match for the actions of a solitary little Turkish minelayer, the Nusrat.

HMS Ocean, HMS Irresistible, HMS Goliath, the French battleship Bouvet and five other cruisers were sunk within hours. The strong currents and geographical bottleneck formed by the Dardanelles also helped in setting up the British fleet for easy attack by German U-boats.

Equally ill-conceived was the expeditionary land force of British, Anzac and other Empire soldiers, sent under General Sir Ian Hamilton to capture the Gallipoli peninsula from the Turks.

This force’s over-confidence was evident when, on landing at Suvla Bay, it stopped for tea and a game of cricket. The Turkish army – soldiers defending their homes and with nowhere to retreat – had time to organise and take the high ground from the few New Zealanders unlucky enough to have been sent to defend it.

Without that crucial four-hour delay, the outcome might have been different. In all 250,000 men were lost by each side – a thousand a day. A campaign expected to last only 11 days ended inevitably in retreat, but not until eight months after it had begun.

It was a military disaster. Winston Churchill, then First Lord of the Admiralty, reported that the ghosts of Gallipoli would haunt him for the rest of his life.

Three groups of wrecks

Today it’s an altogether more peaceful place, protected as a Turkish National Park. Much of the tourism centres on the WW1 memorials, with 40 Allied war cemeteries located on the Gallipoli peninsula.

For divers, the obvious attractions are the many ships and boats wrecked between April 1915 and January 1916. Several hundred sank in the coastal waters between Anzac Cove and Suvla Bay on the western side of the peninsula, and the locations of 216 have been discovered to date.

We can divide the wrecks of this campaign into three groups, according to their locations and depths. In the first group, we must count the war wrecks lying to the north-east in the Bosphorus strait, along with the French warship Bouvet and the British warships Irresistible and Ocean, sunk in the battle of 18 March, 1915.

The arrival of German submarines in the region led to the second group of wrecks, lying in Saros Bay in the Aegean Sea.

The third and final group consists of the ships and submarines that fell victim to Allied submarines that had managed to reach the Sea of Marmara by crossing the Dardanelles quietly in deeper water.

The selection of accessible wrecks outlined below lie on both sides of the Gallipoli Peninsula:

Lighters

Lighters were sheet-iron boats used by the British in WW1 to land infantry and carry provisions. Many were sunk during storms and by gunfire, and several remain at diveable depths. There are two examples in Morto Cove at 30m and only a few metres apart. One had a steam boiler, which lies on the sand nearby, and both attract schools of fish and rays.

HMT Lundy

The ex-trawler Lundy sits 28m deep in Suvla Bay and the wreck remains in good condition despite its age. A support vessel during the Gallipoli campaign, it was sunk by torpedo in 1915 and is now home to a cargo of octopuses, lobsters, conger eels, scorpionfish and small schooling fish, which can be found amid the war supplies and ammunition aboard.

Much of the wreck is now encrusted with sponges, with shoals of bream and gobies inside. Unfortunately, the bell and compass have been stolen.

HMS Louis

Not far from the Lundy, near the Buyuk Kemikli headland, is the wreck of a destroyer that is most notable for its armoured steam boilers. The wreck’s location near the shore and maximum depth of 15m make it an excellent dive, even for relatively inexperienced divers, and it offers some beautiful photographic possibilities.

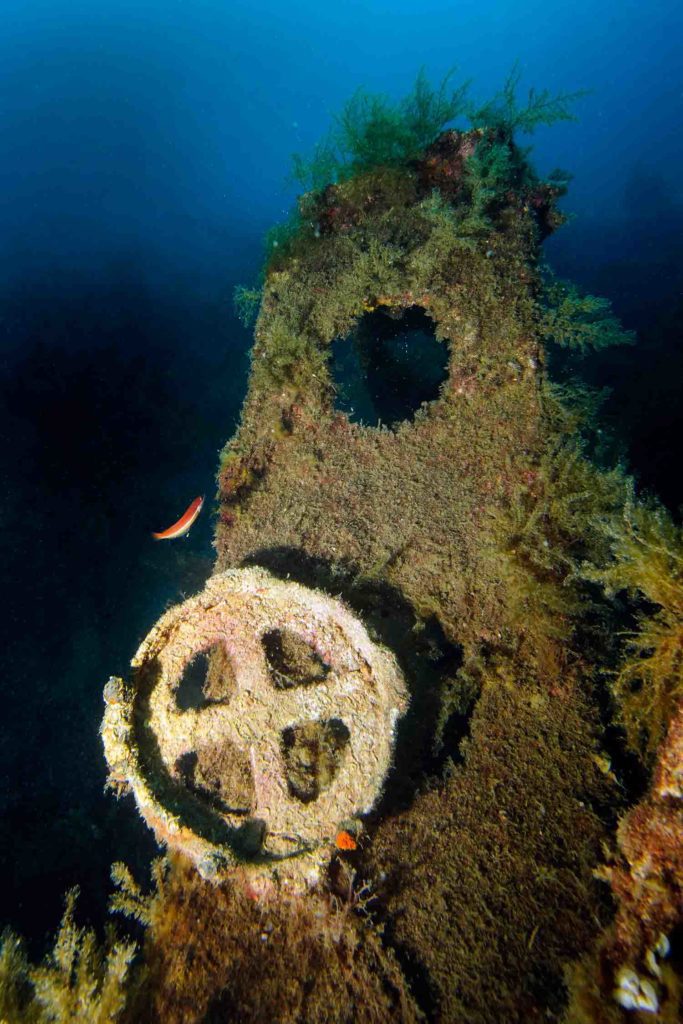

HMS Majestic

When the Royal Navy was seen to retreat to the safety of the open sea, the morale of the land forces was severely damaged. HMS Majestic, one of the oldest Dreadnoughts, was sent back to patrol the coast as a sacrifice to political expediency, but was soon sunk by U-21 in May 1915, with the loss of 49 men. The wreck lies in Morto Cove, with its stern on the sand at 29m and its bow 18m deep.

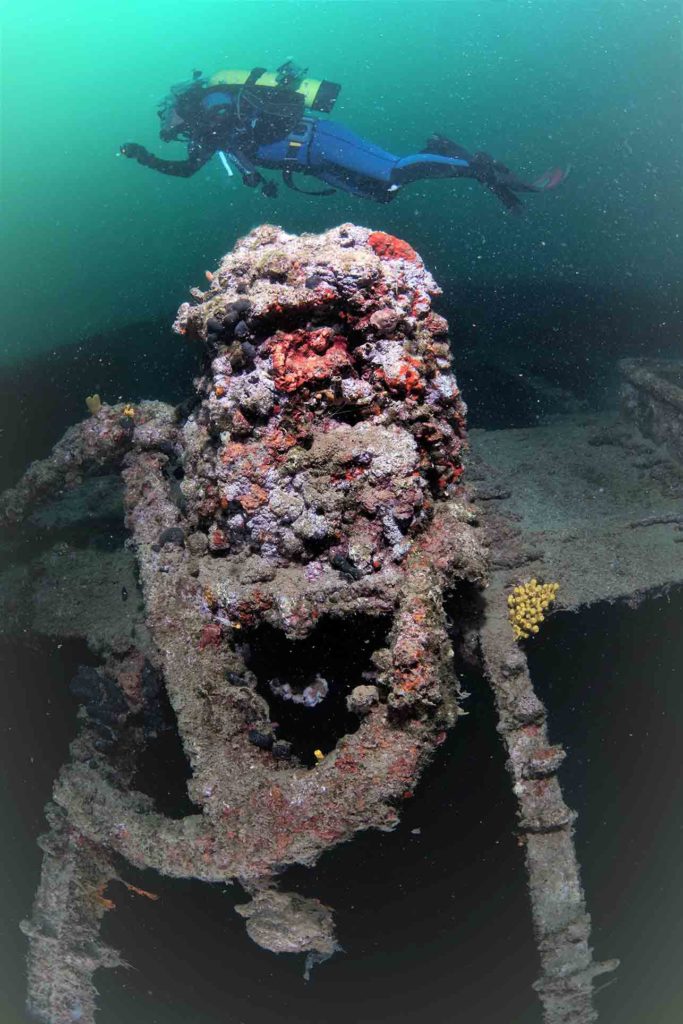

Schooling fish including bream and dentex have made the shipwreck their home. Some sections were dismantled in the 1960s but plenty remains to interest the visiting diver, including a barnacle-encrusted cannon, and the crow’s nest some 10m away.

HMS Triumph

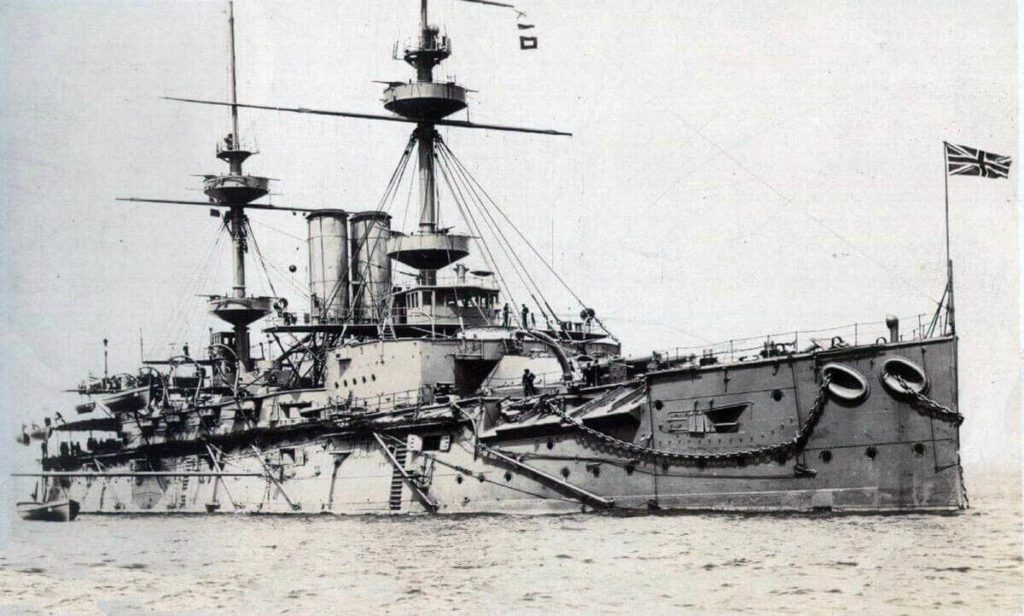

This 133m warship was one of the three, with HMS Albion and HMS Cornwallis, that commenced the shelling of Turkish strongholds. On 25 May, 1915, she was hit by a torpedo from U-21 over a distance of 370m.

Triumph sank off Kabatepe in less than half an hour but that was enough time for almost all of her crew to be rescued by HMS Chelmer. The wreck lies inverted in 72m. With visibility of 15-20m, this is a great technical dive offering many interesting photographic opportunities.

Chartage

The 121m-long French transport steamship Chartage was also sunk by U-21, with the loss of 75 seamen, while carrying military supplies.

She had spent several lucrative years plying the trade routes, and her location remained a mystery for many years until wreck researcher Selcuk Kolay found her off Seddul Bahir a century after her sinking, in 2015. His technical team were able to make a positive identification on their first dive.

The shallowest part of the wreck lies at 55m but it continues to 85m deep. Currents can be strong and visibility is variable, though generally 10-20m. These remains are remarkably well-preserved and rest in sand decorated by many colourful sponges and other marine life.

HMS E-14

For a long time the position of this British submarine remained another mystery, but eventually the wreck was found by a fisherman from Canakkale, at a depth of 21m, partially covered by the shifting sands of Kumkale. The 60m-long, 635-tonne sub was sunk later in the war, on 18 January, 1918, and all 25 seamen were lost.

Continuous currents

Because of the heavy ship traffic in the Dardanelles, there are restrictions on navigation and scuba diving in many parts of the strait. The continuous currents in the region can sometimes reach 4-5 knots, and at times it can be necessary to fight three different flows to reach the bottom.

Many significant wrecks are located at depths exceeding 50m, the preserve of technical divers. However, with permission from the responsible agencies diving on some of these deeper wrecks can be possible.

Divers visiting for the wrecks should put some time aside to visit Gallipoli Peninsula Historical National Park to see the landing beaches, WW1 memorials and the well-kept cemeteries of the Anzac campaign.

GETTING THERE: The best way is to fly to Istanbul – if your dive operator can arrange to pick you up from the airport and transfer you down to Eceabat. It’s about 3.5 hours of fun driving away, and make sure to stop in Tekirdag for a quick Tekirdag special köfte and beer. Or you can fly from Istanbul to Canakkale and cross the strait to Eceabat by ferry, or over the new bridge connecting Asia Minor to Europe. Your dive-boat will be in Kabatepe, only 20 minutes away.

ACCOMMODATION: There are nice hotels that can suit groups or families In Eceabat or the Kabatepe area. There are also B&Bs in Eceabat with lovely views of the strait. The Kum Hotel in Kabatepe caters for many divers, or try Crowded House in Eceabat. You could also choose to stay in Canakkale City, which offers plenty of diversions after diving.

DINING: Turkish cuisine is largely the heritage of Ottoman cuisine, a fusion and refinement of Mediterranean cuisines that are rich in vegetables, herbs and fish. I highly recommend meze, the selection of small dishes served as appetisers.

DIVING: The season starts in May, although the best time to be in the region is September. If you are into technical diving, be sure to contact your dive centre well in advance to organise permits and logistics. Troy Dive Boat, run by Burhanettin Aktansoy, arranges expeditions for technical divers, while for recreational divers wishing to dive the more accessible wrecks Byem Diving Centre visits them daily.

Expert on Turkish diving, writer, documentary photographer and conservationist Mahmut Suner is the Editor of Triton dive magazine and the author of 10 books, including the comprehensive free digital dive-guide Underwater Wonders of Turkey

Also on Divernet: Underwater Parks Boost Turkey’s Dive Appeal