POLAR DIVER

Sub-Antarctic

It was a bucket-list trip for three divers – and MARK HATTER had been training for two years to qualify to go!

Appeared in DIVER May 2018

DATELINE: 26 JANUARY; 64°17’S, 064°01’W, 9 AM. I am again binge-watching Antarctica documentaries in my cabin. There isn’t much else to do while traversing the infamous Drake Passage between Tierra Del Fuego and the Antarctic continent.

It takes two and a half days to make the transit – if the passage isn’t raging.

Our juju has been good. The sea in the passage has been around 10m, child’s play for the ice-breaker Ortelius and its international crew.

Scopolamine patches and liberal fills of wine at lunch and dinner have helped with the crossing. That, plus round-the-clock movies on the tube.

I am into the second half of the BBC film on Sir Ernest Shackleton when there is a knock on my cabin door: “Mate, you need to come see this now!” Paul Shepherd, my friend and diving buddy, is standing there, animated. “It’s amazing, come to the front deck!” he urges. Spinning on his heels, he heads back outside.

I grab a camera with a long lens, pull on a light rainproof parka and head to the bow of the ship. Along the way, I realise that the until-now constant rolling of the ship has ceased.

Opening a side door to the outer deck, I find the railing already lined with people, some squeezing between shoulders to gain a better vantage point to see the breathtaking Elchior Islands on the port side and, to starboard, Anvers Island in the Gerlache Strait.

Paul and his wife Kristen are at the bow with dozens of other passengers, most shooting stills or video of a massive iceberg, replete with penguins, passing close to port.

I FEEL THE THROB of Ortelius’s jumbo diesel engines below my feet, and take in the surprisingly wide palette of whites, blacks and blues reflected from snow, rock and ice beneath a cloud-textured sky. Finally, after two years of planning and training, Paul, Sean Markley and

I are only hours away from a bucket-list diving adventure that many have described as “just plain crazy.”

Our juju is strong. There are only 10 divers booked on this voyage (Ortelius can book up to 24), including us. I have been training for the better part of two years to get to this place by exceeding experience requirements mandated by the Ortelius diving expedition team.

Aboard the vessel, Henrik is our dive-team leader. A stoic Swede with a Viking jaw and an unflappable demeanour, he portrays cool leadership that only long polar-diving experience can develop.

UK coldwater diving experts Catherine and Michael round out the dive-crew and, between the three of them, represent an impressive five decades of combined coldwater experience.

An hour later, we gather with “the Team” and the seven other divers for our first Antarctic dive briefing as Ortelius approaches Cuverville Island. Henrik reminds us that we’re on our own. The team will not act as divemasters; they are there to transport us to the locations and assist with doffing and donning of equipment, if needed.

We have earned the privilege of being able to dive Antarctica by meeting those experience-threshold requirements.

OUR FIRST DIVE OFF Cuverville Island is essentially a self-checkout without camera, in a shallow bay with no current where we can figure out weight allocations and become familiar with our kit in sub-0°C water.

Surprisingly, we guess our weight requirements perfectly, dive to 20m and last the full 40-minute bottom-time limit without issue.

We congratulate ourselves back on the RIB for completing our first polar dive.

Later in the day we dive along a vertical wall near Brown’s Station that drops away from the surface to several hundred metres. Visibility is about 5m, not surprising as we’re diving Antarctica in mid-summer, when 24-hour sunlight creates the plankton blooms that fuel the entire food-chain here.

Henrik recommends shooting macro, as the wall offers little dimensional relief needed for aesthetic wide-angle imagery. And we are not disappointed; between the varieties of colorful sea stars it is the marine “bug life” that captures my attention. Many of the isopods we find seem to be aquatic versions of terrestrial insects. In particular, we find one resembling a centipede and another that looks like a woodlouse.

Twenty minutes into the dive Paul frantically signals for me to turn round. I carefully spin, trying to maintain neutral buoyancy without flooding more ice water into my 7mm hood – and see nothing. Still, he gesticulates excitedly. Sean and I both turn again – nothing.

Back aboard the RIB, Paul is animated and incredulous. “Guys, did you not see the crabeater seal swimming just a metre behind you?” Sean and I look at each other, dumbfounded, and shake our cold heads. “No!”

Paul has had one of the iconic but rare encounters for which divers hope in Antarctica, by swimming with one of the continent’s large animals. Despite the excellent macro photography, he will still be kicking himself days later for not having had his wide-angle kit for the drive-by encounter left in his mind’s eye.

We spend the next hour slowly motoring through a thick field of slush ice looking for seals rafting on bergs sculpted by wind and water. There is no wind now, and fat snowflakes drift aimlessly down from a dull grey sky.

The weather changes quickly in Antarctica and is fickle enough to go from calm to gale and back again in a matter of hours. In a word, the weather is moody.

Once again our juju is good. The weather breaks and warms considerably for our optional “camp-out” that night on a snow-covered island.

AT 9PM WE BIVOUAC with 30 other guests in double sleeping-bags dug into grave-sized depressions in the snow.

I wake at 3am for biological reasons, but hesitate in my warm bag, listening to the explosive thunder-cracks of glaciers calving in the sound around our small island.

The Antarctic sun is low on the horizon behind a three-dimensional layer of mixed clouds. But the light is strong enough to bring out the muted colors of the mountains reflecting on the still water, so I grab a camera before I head to the Portapotty (we take everything with us back to the boat to keep the island pristine, even our waste).

On day three we arrive at 65° 07’ S, 064° 02’ W, the furthest south Ortelius will take us on this voyage. Between Pleneau and Petermann islands we plan to dive an iceberg. This is on all of our dives-to-do lists, but we learn that iceberg-diving in the Antarctic summer is not a simple task.

“The bergs are dynamic – in addition to constant motion on the winds and currents, they are melting,” Henrik tells us in the pre-dive briefing. “This mix can create a deadly combination of instability where the bergs can flip over or calve chunks onto a diver. So we’re looking for

a good, stable piece of ice that can give you a pleasurable dive.”

After kitting up, we spend the better part of an hour wending our way through an ice-field in deteriorating weather conditions looking for the “Goldilocks” (not too big, not too small but just right) berg. Only six of us are diving today, using two RIBs.

Henrik leads in the first boat and finally finds the right berg. As his divers roll into 200m of water on one side of the berg, we do final kit checks and Catherine motors our boat into position.

Then, as if from a page in Henrik’s safety briefing, the wind and current begin pushing our berg into another one nearby.

The conditions have become dangerous and the safety recall to the three divers in the water is initiated – the banging of a long metal pipe with a hammer from the side of the RIB.

The extraction is text-book, the divers quickly surface and are safely recovered before the ’bergs collide. But conditions remain too treacherous to continue, so we abort the dive (and the following dive later in the day) and move to the beach to photograph breeding Adelie penguins.

Sailing north up the Neumayer Channel overnight, we arrive at Wilhelmina Bay the following morning.

Kitted up, we finally find a Goldilocks berg where we experience Henrik’s third difficulty of diving around melting ice – buoyancy control.

Much like a plane navigating through turbulence, the freshwater lens around a berg creates a buoyancy “downdraft” that must be countered quickly.

Yet, once outside the freshwater boundary, the additional buoyancy must be jettisoned just as quickly.

Add a camera-kit to the mix under the frigid conditions and underwater workload can increase exponentially.

We do the dive and collectively agree, tongue-in-cheek, that the next time we go berg-diving, it will be during winter. After all, the water temperature is the same!

ON OUR LAST DAY on the continent, the Ortelius sails to Deception Island in the South Shetland Islands. Deception is a semi-active caldera venting hints of sulphurous gas, even against the gale that still plagued us from the previous day.

But the caldera’s bay is largely protected and the wind direction is favourable to dive a section along the eastern wall near a 19th-century whaling station.

“We have found whalebones on previous dives here,” Henrik tells us at the briefing. “The bottom slopes toward the centre of the bay – again, limit your dive to a maximum of 40 minutes and 20m.”

By now kitting-up is routine. We make our way to the RIB, and once again launch with a priority over the other guests, who will visit the ancient whaling station and the fur seals lounging on the black-sand beach.

The wind is stiff, whipping sub-zero saltwater into freezing spray as Catherine drives Paul, Sean and me to the beach. Several divers have opted out of the dive.

It’s snowing again, and the sky is dark, with heavy clouds scudding in from the south-east. But we find the water relatively clear – about 10m visibility – as we settle to just above the black sand bottom at 10m.

In almost twilight conditions, we work our way down the slope to deeper water.

In contrast to earlier dive-sites, there is no macro algae here but the black sand bottom is alive with different kinds of sea life: brittlestars, urchins and anemones.

Tagging behind Paul, I see him move to shoot what appears to be a large, white rock festooned with critters.

My senses are dulled in the sub-zero water but it finally dawns on me that what appears to be rock is actually whalebone, mostly buried in the volcanic sand.

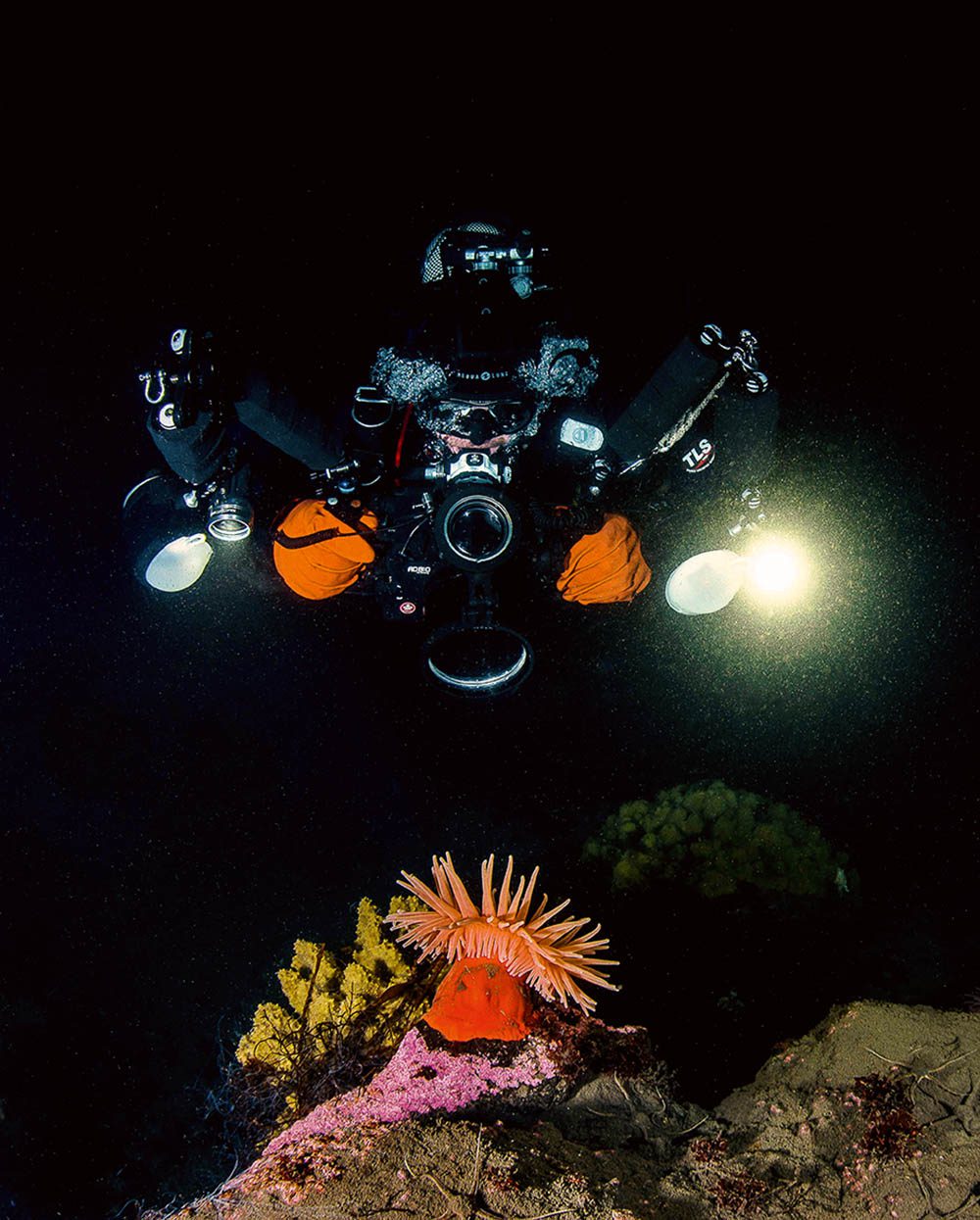

AT 20M WE FIND MORE whalebones and a small rocky ledge. The dinner-plate-sized orange anemones like the deeper water and cling to anything above the sand that provides a foothold.

I ponder how old these invertebrates might be as I line up for an image.

“Marine biologists have estimated that Antarctic anemones can grow to a metre in diameter and live for up to two centuries.” Henrik had presented this amazing factoid in his underwater wildlife lecture on board the Ortelius earlier in the trip.

It was difficult to wrap my head around the fact that the anemones on this ledge might predate the whalers who came to this caldera in the late 19th century.

Sadly, this was our final dive, the culmination of planning and training over years for Paul, Sean and me.

Back onboard we celebrated our accomplishment at the bar with liberal fingers of Scotch. And we began planning phase two of polar diving for the summer of 2019.

After all, you can’t dive one end of the Earth without diving the other, right?

FACTFILE

GETTING THERE> Fly London Heathrow to Buenos Aires with BA. Book Aerolineas onward to Ushuaia, the departure port for Ortelius. You will need your own diving kit, so be prepared to pay extra for two checked bags plus overweight charges on all flight legs.

DIVING & ACCOMMODATION> Oceanwide Expeditions, oceanwide-expeditions.com

WHEN TO GO> The Ortelius begins operations in November and runs expeditions through March during the Antarctic late spring to early autumn.

MONEY> Euros are widely accepted.

HEALTH> You will be days away from rescue for a significant diving injury, so there are depth and bottom- time limits and minimum experience requirements. A general doctor onboard can treat minor injuries or provide patient stabilisation.

PRICES> Flights around £2000. A 10-day expedition costs around £10,000.

VISITOR INFORMATION> www.argentina-excepcion.com