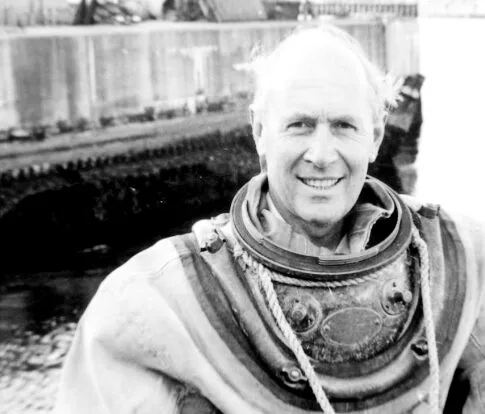

Shipwreck-diver, researcher, curator and author Richard Larn OBE, whose passion and expertise helped to define modern British wreck-diving and maritime history scholarship, died on 14 January at the age of 94 following a short illness.

Born in Norfolk in 1931 and raised in Great Yarmouth, Larn embarked on the process of teaching himself to dive at the age of 16 – by plunging into the Thames equipped with ex-Nazi kit.

It was two years after the end of WW2 and he and a friend, a Navy diver, had each bought Dräger submarine escape apparatus advertised in Exchange & Mart for 10 shillings a set.

“They actually had the German spread eagle and swastika and everything,” said Larn later, talking to Toby Butler of the Mapping Museums project.

The descent had landed the pair on a submerged river steamer. “I thought: ‘Wow, this is fantastic, if every time you jump into the water you find a ship! And I just got hooked on shipwrecks from that moment – I started researching and researching.”

He would stop diving only when he was 80, though the shipwreck research always continued.

Around the end of WW2 at the age of 14 Larn had been sent to join a Royal Naval training ship and enjoyed the 18-month experience. He went on to become an apprentice deck officer in the Merchant Navy, sailing to and from South America for five years and becoming a second mate.

He then transferred to the Royal Navy, initially serving in Korea in the later stages of the war there, and would remain with the service for 22 years.

He became a chief petty officer, qualified as a weapons mechanician and Naval diver, and claimed to have initiated the idea of an “aircrew diver” role when stationed in Malta, where he would drop kitted-up out of a Dragonfly helicopter miles offshore to help recover gunnery-target aircraft.

Sport diving in the Navy

In 1957 Larn joined the British Sub-Aqua Club and was its deputy diving officer in 1961 and 1962. The following year he fronted a campaign to make recreational diving an “accepted occupation” in the Royal Navy.

The Admiralty was reluctant to take responsibility for possible accidents to members of a Royal Navy Sub-Aqua Club, but Larn got round the objections when he was permitted to use the name Naval Air Command Sub-Aqua Club, and became its first diving officer.

“We had a sub-aqua club in every Royal Naval air station around the country,” he told Butler. “We had at least a couple of thousand guys in this organisation and we had annual expeditions and everything else.”

Throughout Larn’s naval career he said he would “read every word I could find about shipwrecks”. Having learnt about the Association, the British warship that had grounded and been lost off the Scilly Isles in 1707 in what was regarded as the greatest maritime disaster of its age, he was given the go-ahead to organise a trip to look for it with 12 divers using a minesweeper in 1964.

These Admiralty-funded Association expeditions became an annual event. The dive-team’s eventual discovery of the ship’s bronze cannon and gold coins in 1967 gained international attention and was only the second finding of an historic shipwreck in the British Isles in modern times. As it happened, Larn had been unable to join in that year because he was on duty in Singapore.

After the extended expedition ended, “everybody with a diving cylinder in the country came to Scilly,” said Larn. “They tore it to bits, they took everything that there was away. It sold at auction and you could go down the pub and buy a coin for a quid.” However, he did lead three more of the annual expeditions.

Historic wreck protection

Larn had tried unsuccessfully to interest the National Maritime Museum in displaying Association artefacts but said that it “didn’t want to know about shipwrecks. There was no Nautical Archaeology Society, there were no regulations, there wasn’t an English Heritage.

“It was all to do with castles and burial-sites and land-sites and Romans. And to suddenly introduce shipwreck and maritime affairs into this closed museum world, people were looking down their noses at us: ‘Who are these peasants?’”

In 1969 he approached St Ives MP John Nott to explain that UK divers would discover more historic shipwrecks and that some sort of protection from looting was needed for heritage sites. Nott introduced a Private Member’s Bill that led to the passage of the Protection of Wrecks Act 1973.

Larn said that the Association discovery in Scilly secured his “continuing love for both the islands and their maritime history” and he would become a regular visitor over the years before moving there permanently.

“The Isles of Scilly probably have more shipwrecks per square mile than any other place on Earth,” he told Butler. “Over the years I have dived on a few and some of their stories are terrific. Everything from disaster and death to sunken treasure – the Isles of Scilly has it all.”

After the Navy

After retiring on a Navy pension in his 40s, and concerned that at the time so many commercial divers were dying in British waters every year, Larn co-founded a commercial diving school called Prodive.

This government-approved diving establishment, one of only three in the country, introduced a 12-week training course to certify all new divers going to the North Sea.

The school was later given the opportunity to move to a site at Charlestown in Cornwall. Here in 1976, with his second wife Bridget, Larn founded the Charlestown Shipwreck & Heritage Centre, based initially on his “garage-full” of underwater artefact finds. He had anticipated some 20,000 admissions a year but from the first year welcomed around 75,000 visitors.

The centre became one of Europe’s most significant public displays of undersea discoveries, containing 8,000 artefacts from more than 150 shipwrecks, and the Larns ran it until 1998.

In 1992 Larn sold his shares in Prodive to his business partner to allow him more time for underwater treasure-hunting around the UK with his wife.

He led successful expeditions to recover silver coins from the VOC ship Campen off the Isle of Wight, but counted as most memorable his retrieval of millions of newly minted copper coins as well as ingots and artefacts from the English East Indiaman Admiral Gardner on Kent’s Goodwin Sands.

Other wreck projects on which he was involved included the Coronation, Dartmouth, Dollar Cove, Ramillies, St Anthony, Santo Christo de Castello and Schiedam.

Larn also played a crucial part in the raising of another international sensation, the Mary Rose in 1982, though this was kept secret in accordance with the wishes of the project’s archaeological director Margaret Rule until after her death in 2015.

There had seemed to be no way to raise the ship without destroying the many heavily concreted artefacts surrounding it, but when Rule consulted her old friend Larn about this he fell back on his knowledge of underwater explosives, gained from his time in the Navy.

After using small charges designed to pop the remains out in manageable sections with minimal damage, the ship was raised successfully.

In 1986 the Larns undertook their first business venture in the Scilly Islands, taking over a failed butterfly centre that became the Longstone Shipwreck & Heritage Centre, an echo of the successful Charlestown project.

The Shipwreck Index

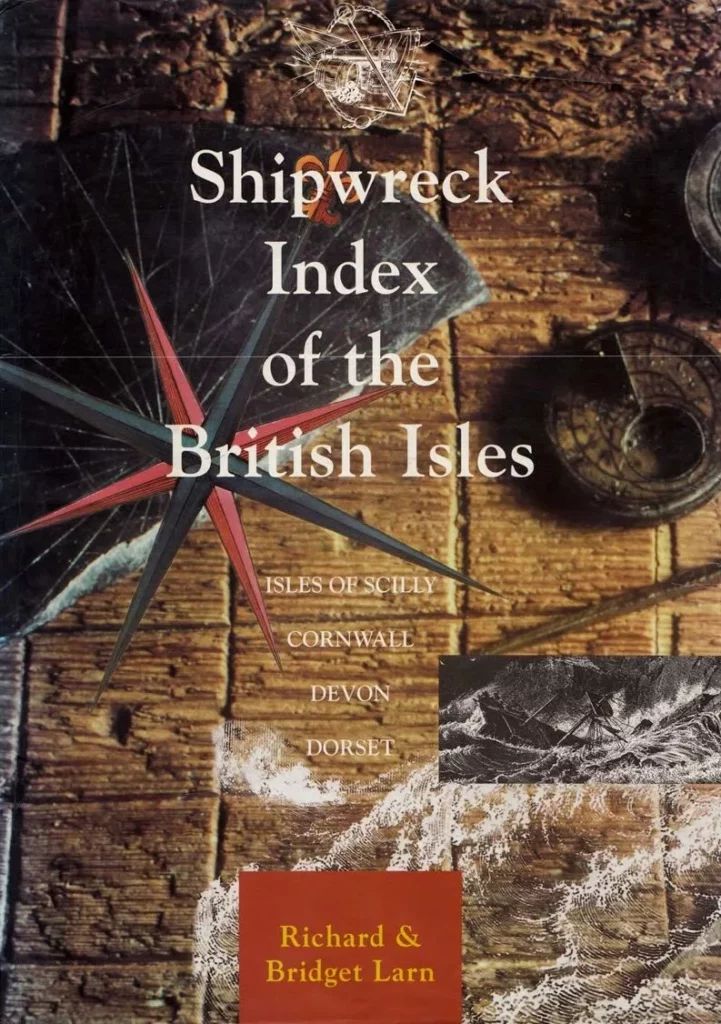

In 1991 the couple returned to Cornwall to undertake the strenuous research required to produce their six-volume magnum opus, The Shipwreck Index Of The British Isles.

Commissioned by Lloyd’s Register to be written over a 10-year period, and documenting some 45,000 incidents, this was recognised as the most comprehensive resource of its kind for divers, historians and enthusiasts.

“We devoted every single working day, six days a week,” recalled Larn. “We employed two girls who did nothing but keyboard work. Bridget was doing the cataloguing and giving the girls the work and I was out on the road collecting the information, all over the country.”

His only regret was that the decade spent on this massive print project came before the digital age, He later started a company that enabled the data to be transferred to Shipwrecks UK.com along with that from the Shipwreck Index of Ireland, so that the volumes could be kept up to date and accurate.

Larn’s first book Cornish Shipwrecks – The South Coast, written while he was still in the Royal Navy and published in 1969, had been the first to cover shipwrecks on a county basis and proved successful.

He went on to write or co-author another 70 or so books, one of his favourites being his 2019 Sea Of Storms, an illustrated account of some of Cornwall and Scilly’s most significant wrecks. Two of his most popular titles with scuba divers were the Diver Guides to South Cornwall, and to the Isles of Scilly & North Cornwall.

The Larns eventually settled on St Mary’s in the Scilly Isles, where they ran self-catering accommodation. Larn was licensee for the Bartholomew Ledge and Tearing Ledge wreck-sites, and from 2010 served as president of the International Marine Archaeological & Shipwreck Society, which holds the annual Shipwreck Conference at Plymouth University.

In 2009 an OBE for services to nautical archaeology and marine heritage was recognition of Richard Larn’s efforts to bring undersea exploration and history to a wider audience.

Such sad news. Larn made an amazing contribution to maritime historical knowledge, he leaves an amazing legacy.

To note the Shipwreck Index of the British Isles was commissioned by Lloyd’s Register (not by Lloyd’s of London as noted in the article). We are still very interested in shipwrecks and in learning from them.

Sending our thoughts to the family.