The British Society of Underwater Photographers, better known as BSoUP, was one of the first underwater photographic societies in the world. Now in its 50th year, co-founder COLIN DOEG guides us through half a century of photographic evolution

ON A COLD, DARK NIGHT in November 1967, sixteen people crammed into the front room of a house in north London. They had a common interest – underwater photography – and already enjoyed varying levels of success at obtaining images from beneath the waves.

The group included two Kodak employees, the colour print manager of what was regarded as the best photographic laboratory in London, the assistant editor of the world’s largest-circulation evening newspaper at the time, people from advertising and public relations and a widely respected GP and diving doctor.

Two hours later the British Society of Underwater Photographers had been created, officials elected, objectives set and a meeting arranged for the following month, so that we could each show and discuss some of our pictures.

Not bad when you consider that it all happened because slides intended for Peter Scoones had been sent to me in error. But that was how we met, discovered that we each had the idea of forming a photographic society, and ended up circulating diving clubs telling anyone interested that we were arranging a meeting to discuss the idea.

That first meeting and many others were held in Peter’s house where, because of the limitations of the room in which we met, slides could at first be projected only at a small size.

We never thought more about that until the next meeting, when we found ourselves gathering in a much larger area. Peter, the original secretary, had knocked down one of the walls so that our images could be bigger. We were impressed.

He began by knocking a hole in the wall and projecting some slides through it, but the pictures were still small.

So he kept enlarging the hole until, finally, he had demolished the entire wall. Only then did he realise that it was a supporting wall!

The shops were closing, so he rushed out and bought a baulk of timber strong enough to stop the house falling down. Those were the good old days. We were not hampered by rules and regulations.

The meeting also discussed the need for a logo. The late Kendall McDonald, assistant editor of the long-gone London Evening News, offered to approach one of the paper’s artists for ideas.

The artist drew a few lines on a scrap of paper and produced the logo that has remained largely unchanged ever since (above). He was rewarded with a packet of 10 cigarettes – we had been warned not to be too generous!

OBJECTIVES AGREED AT THE FIRST MEETING – where I was elected chairman – included fostering and promoting underwater photography in all its aspects, both as an art and a means of illustration, as well as to encourage and make known research and development of techniques and equipment. A forum was set up to discuss ideas and problems of common interest.

The annual subscription was three guineas, payable in advance. That’s just over £3, about the cost of a 35mm film.

More meetings were arranged for the winter, because we would be too busy diving and taking pictures in the summer in British waters.

It was also suggested that the society find a photographic agency to handle members’ work, but Gillian Lythgoe went one better. She started Seaphot, which became world-renowned.

We ran print and slide clinics to help members with advice. These worked well for years but, as BSoUP grew, members became reluctant to expose their faulty images to the ever-larger audiences.

Core-members of BSoUP were from London Branch of the British Sub-Aqua Club. Indeed, if you were keen on underwater photography, you really had to be a member of that branch, and it was a select group from there that provided the society’s formidable technical base.

Rather than do National Service, Peter Scoones signed up to the Royal Air Force as a regular so that he could “ learn something useful”. He was trained as a photographer and became adept at stills and cine as well as repairing cameras.

Coming from a sailing family, he was active in the RAF’s sailing club in Singapore, where he was stationed. To speed up the cleaning of the hulls of the boats, he started snorkelling and diving underneath them.

Fascinated by the colourful marine life and scenery, he began making housings for his cameras from Perspex scrap, and helped to form a diving club. It had to create its own training programme and was helped – very unofficially – by Navy divers to use oxygen rebreathers, before changing to air with home-made demand valves and oxygen cylinders discarded after use in aircraft.

Tim Glover worked in Kodak’s research division making, among other things, prototype cameras that soon went on sale.

His colleague Geoff Harwood was a technical advisor whose job was solving customers’ problems, and even building special equipment to meet their needs. He was also the author of Kodak’s definitive leaflet about underwater photography and how to take successful pictures.

The pair were responsible for the creation of the BSoUP data book. A blue folder packed with regularly updated technical information, it was the classic reference source, especially for members unable to attend the meetings in London.

As well as working for an international advertising agency, Mike Busuttili had a keen eye for a good image. As London Branch’s diving officer, he trialled a new training programme so successful that it was adopted by the club, with Mike in the specially created post of national training officer. Later, after 11 years as managing director of Spirotechnique UK, he moved to France as marketing director of La Spirotechnique.

Tim, Geoff and Mike were believed to be the first British divers to venture to the Red Sea and return with successful pictures. They were sleeping on the beach and just walking into the water. Others used to hire cars, park on the beach, sleep in them and wade in with their cameras.

THE CONTRADICTION OF my interest in underwater photography was that I did most of my National Service in Egypt, within 100 miles of the Gulf of Suez, but never owned a camera.

I was a member of the Buckshee Wheelers, a Forces cycling club. Riding bikes donated by the UK cycling industry, we held club runs and races – often chased by packs of wild dogs with slathering jaws and teeth as fearsome as any shark.

Subsequently I learned to dive and, because of my background in newspapers and PR, realised that there was a demand for words and pictures about the new realm capturing everyone’s imagination following the success of films on TV and in the cinema about the exploits of the two great pioneers: Hans Hass and Jacques Cousteau. So I bought a 7s 6d paperback and attempted to teach myself.

Another original member was Phil Smith, a professional photographer based in Dorset. Later we were joined by Ley Kenyon, a photographer and film-maker who also enjoyed fame as the forger involved in one of the biggest escapes from a prisoner of war camp in Europe, by prisoners concealing themselves inside a huge gymnastic “horse”.

Warren Williams joined about two years later. Out of curiosity he used to swim in ponds on Hampstead Heath wearing goggles and using a crudely “waterproofed” torch to see what was there. By the time he was 16 he was trying to make his own breathing apparatus.

After National Service he faced the dilemma of deciding whether to join Vogue magazine as a trainee photographer or return to his trade as a scientific instrument-maker.

In the end instrument-making won, and he brought a new standard of workmanship to the housings and other equipment being made by those fortunate enough to have their own workshops.

Otherwise, you had to find someone to make a housing for your camera or buy a commercially made outfit. The supreme housing was the Rolleimarin. Developed by Rollei in conjunction with Hans Hass, it was a delight to use, especially in clear, well-lit water. However, it was expensive and took only a 12-image film – just think of that, all you memory-card users!

A housing was also available for a Leica. That wasn’t cheap either, but the camera took a 36-exposure film.

Then the CalypsoPhot came on the market. I remember seeing one in a shop window in France. It cost £46.

After two years of dismal results using a £10 camera in a crude housing, I bought one in a last, desperate attempt to produce a decent image.

They were exciting times. Gill Lythgoe calculated that only one in a million people in the UK was an underwater photographer. So we were special. We were pioneers. We were an inspiration to each other. We buzzed with excitement and ideas. Life was enormous fun, and I hope it continues to be that for everyone who takes a camera under water.

DURING ONE GLORIOUS PERIOD, committee meetings continued until the last bottle was emptied, and we never kept any minutes. This had the great advantage that we could discuss the same topics every month, because no one could remember what had been said previously.

Nevertheless, much came out of that period that is taken for granted these days. In the battle to photograph a full-length diver in British waters, the likes of Peter, Geoff and Tim ground wide-angle lenses from pieces of Perspex.

At the same time, dome-ports started to be made. They were a cheaper solution to overcoming the way light bends due to refraction when it passes through the air-water interface. To do this, Perspex sheet was warmed and softened in an ordinary oven before being clamped in a special rig so that compressed air could be used to gently form it into shape.

Electronic flashguns of all shapes and sizes began to be protected in housings of various types to replace flash-bulbs, which tended to burst into light only when connections were perfect. Today’s flashguns are smaller, often more powerful and much more reliable.

Soon it was realised that different ports could be created for different lenses, provided they all fitted a standard-sized aperture in the body of the housing. So interchangeable ports were created.

The two features missing in those early days were the automatic-exposure features of cameras and flashguns. These transformed picture-taking.

There was an enormous thirst for knowledge in those days. In many ways, it was more inspiring to learn by meeting people at talks and lectures than, as we do these days, by trawling websites, even though they are a source of much more information.

Nevertheless, it was encouraging to learn that a leading commercial photographer earning thousands of pounds a day would have to send his darkroom staff home and work from dusk to dawn, albeit with the help of a bottle of Scotch, to finally produce the one image he knew his client required.

BSOUP’S LEGENDARY SPLASH-INS started soon after our formation. Initially we met somewhere convenient to London, usually Shoreham in Sussex, to dive as we wished and meet the following week to show each other our results.

Subsequently the venue moved to Swanage Pier – then little more than three hours’ drive from central London.

Images taken under the pier or in nearby Kimmeridge Bay regularly won prizes in competitions. Both sites offered the essentials for good pictures – they were easy to reach and we knew what was there.

Indeed, the area became so familiar that we could envisage potential images and plan to take them. If one visit failed, we knew we could return repeatedly until we had perfected the shot. We treated pier and bay like a photographic studio.

Phil Smith, the first to win the coveted title of British Underwater Photographer of the Year at the film and photographic festivals organised for many years by DIVER magazine, took his winning image of a tompot blenny under the pier.

Some years later Martin Edge, author of the acclaimed The Underwater Photographer series of books, even arranged for several divers to position flashguns round a blenny’s hole for his own version.

Martin regarded our meetings as so important that he drove from Dorset to London every month. He is now one of the most respected gurus on underwater photography, teaching divers how to take pictures as well as arranging expeditions and dive trips.

The idea developed of everyone diving in the same area on the same day for a specific period of time and afterwards meeting to see who produced the best images. We called it a Splash-in, and so the idea of a one-day shoot-out was born.

We suspected that it was from our idea that these popular competitions spread throughout the world.

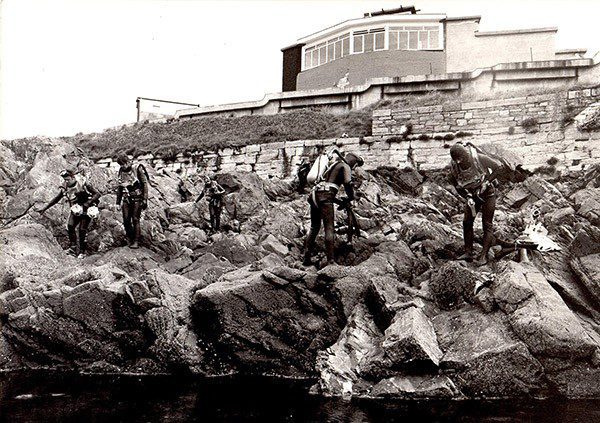

After some years we were invited to move the Splash-in to Fort Bovisand Underwater Centre in Plymouth, and it remained in that area until being replaced by the British and Irish Underwater Championship in 2015.

The original event was held every year, come rain or gale. Often the weather was so bad that everyone queued at nearby rock-pools for their turn to wade in and try to produce a winner. Competition was intense. Many went to Plymouth a week early to check out the area in advance.

Competitors collected one marked 35mm colour film to be exposed in the vicinity of Plymouth. The films were processed the same evening, so that competitors could select their entries for judging by the waiting audience of photographers, friends and local divers.

Processing as many as 70 or 80 colour films by hand within a few hours once a year didn’t always go to plan. Some years lights were switched on at the wrong moment, or chemicals not changed at the correct time, but such problems were usually overlooked by photographers and audience alike, especially as the hours and the drinks dragged on.

Those were the days when it was a huge advantage to have a darkroom. Otherwise you had to wait until dark and convert a kitchen or bathroom into a temporary one.

In summer, when you were struggling for hours to produce competition-winning entries, it didn’t leave much time for sleep. I used to convert the bathroom, and then wake my wife every hour to ask her which version of a print she preferred.

Eventually we moved, so that I could have a darkroom and we could both could enjoy a better night’s sleep.

OF COURSE, the biggest revolution was the introduction of digital photography and computers. Suddenly you could check that your images were coming out while you were still under water. You didn’t have to bring your exposed films back from a trip and have them processed before you knew if they were OK. You didn’t need a darkroom any more. You could do just about everything in daylight, anywhere you liked.

If your camera took RAW files you could do so much more to save badly exposed images. If you were computer-literate and could use programmes such as Photoshop you could do far more with images than all the darkroom technicians and photo-retouchers.

It’s interesting that this revolution came from attempts to make it easier and quicker for press photographers to take their pictures and transmit them back to their newspapers. Previously they would have to drive like crazy back to their offices or use dispatch-riders to get their films to the darkrooms.

But all that was still many years after BSoUP’s inception, and long after we had been invited to speak at meetings of the Royal Photographic Society and stage a major exhibition of our work at its HQ.

In those early years we also staged two major film and photographic conferences in London, inviting leading photographers and cameramen from other countries.

Today BSoUP continues to thrive, especially with ambassadors such as Alex Mustard, for my money one of the world’s most outstanding photographers.

His images continually improve, yet he is always as generous with his knowledge and advice as the original members. He would have had such a ball if he had been with us at the beginning.

We have also had three particularly successful lady “chairs” in Linda Dunk, Martha Tressler and Joss Woolf – we’re not sexist, we just want the best people for the job – while president Brian Pitkin has made a greater individual input to the society over many years than any other member. Roll on to our full century.

CAPTION KEY

Photographers clamber over rocks festooned with slippery seaweed to enter the water at one of the first Splash-ins at Fort Bovisand in the early 1970s.

A photographer in action in clear, well-lit water near Newton Ferrers, Devon, in the 1960s.

Divers ascending the shot line after a dive with Club Med in 1963.

Yes we know… you wouldn’t get away with a photo like this now, but times were different in the Mediterranean in 1965.

Tim Glover (right) and Peter Dick carefully ease a Rolleiflex camera into its housing back in 1959

Glover festooned with cameras and other equipment during a dive off the Italian island of Giglio in 1962; a band performing for Peter Scoones in the early 1970s.

Colin Doeg and cameras at Eilat, Gulf of Aqaba, in 1994

more now non-PC behaviour as Geoff Harwood feeds fish from a broken sea urchin in Giglio in 1962

taken in 1979, this display shows the wide variety of equipment already designed, made or modified and used by Warren Williams for his photography.

Bromley BSAC play Murderball, their version of underwater rugby in the early 1980s

Peter Scoones in 2007 demonstrates his latest video outfit to Warren Williams (centre) and Tim Glover (right).

A classic fish portrait taken in 1963 by Colin Doeg near Tilly Whim Caves, Dorset

1970s fashion shoot by Peter Scoones. Today freedivers are popular as models, but in those days models were usually tied down to the seabed and fed air by standby divers.

Careful use of flash produced this dramatic image, a Splash-in winner for Warren Williams in 1972.

Use of a polecam – basically a camera attached to a pole – enabled Williams to reveal these unexpected colours in a river in 2016. Peter Scoones was the first wildlife underwater cameraman to conceive the idea of videoing killer whales in Norwegian waters and great white sharks off South Africa in this way. Today sophisticated versions are universally used by cameramen, who do not need to be trained divers.

Rays of the Spectrum, the first photograph taken in British waters to win an open underwater competition. It was taken in Kimmeridge Bay, Dorset, by Colin Doeg in 1967 – and his prize was a complete Nikonos outfit.

Golden butterflyfish in the Red Sea in the 1970s. Balancing ambient light and flash to produce such a natural effect required complex calculations; today it all happens automatically.

Is this the world’s first underwater selfie? Mike Busuttili took this photo of himself and an angelfish in Marathon Key, Florida in the 1970s.

| AN IMAGE THAT MADE HISTORY

TAKEN IN THE LATE 1980S by Peter Scoones, this triple-exposure won the main award at the International Blue Aqaba Competition in Jordan, and subsequently featured in cultural programmes for the benefit of UNICEF. |

Appeared in DIVER February 2017