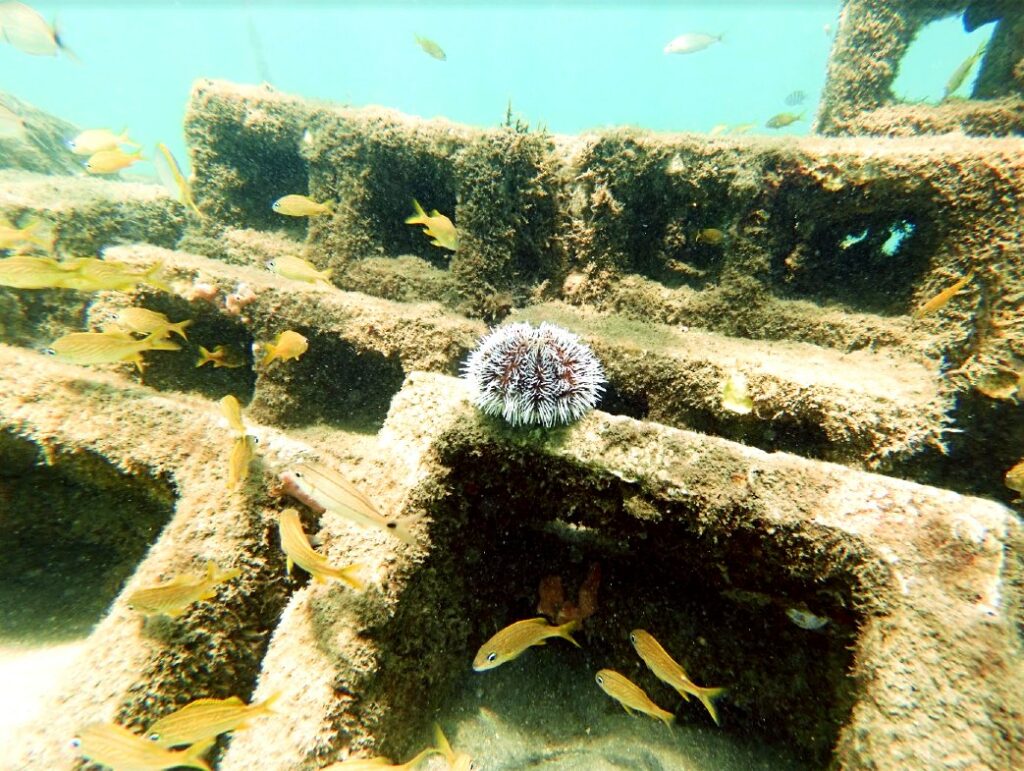

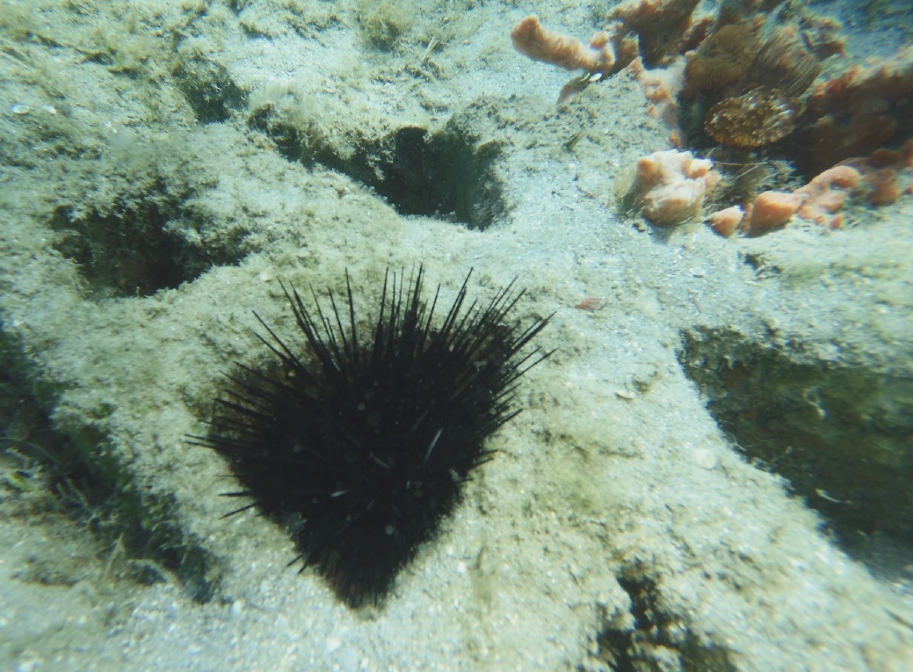

These echinoderms might not be highly valued sightings for scuba divers, but their absence should worry those who value the health of coral reefs already under pressure, says marine biologist JOHN CHRISTOPHER FINE, who took the underwater photos

Our diving doctor used to pull out his knife on decompression stops to break open spiny sea urchins and eat the roe. Instructors used to take spiny urchins up in gloved hands, cut holes through the top and hold the exposed urchin out to divers so that they could watch myriad fish swarm in to eat the flesh.

In those days sea urchins were so prevalent that we would warn both divers and especially bathers to beware. I spent many afternoons picking spines out of forlorn victims.

Sea urchin roe remains a delicacy in Europe, on menus at expensive Mediterranean restaurants, but what was once commonplace is no more.

In 1983-84 a parasitic ciliate – scuticociliate – killed off 98% of these sea urchins in what became a worldwide epidemic. Since that time, researchers calculate that fewer than 12% of the numbers wiped out have been restored.

Sea urchins are echinoderms that have a wide range, from very shallow to some 5,000m deep. Their diet consists of algae, and therein lies the benefit, as well as the concern.

Without these voracious algae-eaters, marine algae grows rampant over coral, eventually covering it and choking out light. Deprived of light, the plants inside coral, calcium carbonate thecas, die. The plants can no longer produce nutrients for the coral through photosynthesis, and that results in coral-bleaching and death.

Corals are dying at alarming rates all over the world from disease and bleaching. Without reefs, life as we know it in the oceans will also die.

200 years old?

Sea urchins are dioecious, a Greek word meaning that the separate male and female sexes exist within the same individual. When the gametes are squeezed out into the water, they are fertilised. Pluteus larvae emerge.

The individual eventually forms plates of calcium carbonate with a dermis and epidermis that results in an endoskeleton. These little critters use a hydraulic system to pump water into and out of their tubular feet to get around. The mouth, or peristome, is on the underside. Sea urchins graze on algae as they move along.

Depending on species, it takes two to five years for a sea urchin to reach sexual maturity. Its size at that stage can vary from about 5-10cm. It can take from a little more than two weeks to as much as 131 days before fertilised plankton-eating urchin larvae settle on a substrate and proceed to grow.

No one is sure how long a sea urchin can live. Some experts say 30-100 years – others, as much as 200 years.

Not so in recent times because, just as with the massive sea urchin kills of the 1980s, widespread deaths were reported in the Mediterranean last summer and the trail of destruction seems to have extended into the Red Sea. Diadema setosum deaths have been reported in the Gulf of Eilat.

From life to death in only two days – Scuticociliate causes spines to fall off and kills the organism.

There are 950 species in the echinoderm arena. Many urchin species have no spines, only a protective hard endoskeleton, but the most prevalent in Atlantic waters off Florida and Caribbean coasts has been Diadema antillarum, with long, tapered spines to protect it from predation.

Hat trick

Some parrotfish brave the spines to crunch through the shell to get at the succulent roe, however, so Diadema sometimes hide during the day to protect themselves against such predation.

Other forms of sea urchin simply disguise themselves. We once found a $5 bill being used by a collector sea urchin as a shield over its top.

These urchins will use just about anything available to disguise themselves on the seabed, whether that means leaves or discarded pieces of wrapper. Fish ignore the urchins, if they’re lucky. In nature, having an advantage means survival.

“Sea urchins, specifically the long-spined sea urchin Diadema antillarum, historically have been powerful herbivores in our coral reef communities,” says Dr Kylie Smith, co-founder with Mike Goldberg of I.CARE (Islamorada Conservation & Restoration Education).

Her research and work restoring coral in the Atlantic Ocean in Florida’s Middle Keys area has resulted in pioneering progress, as covered before on Divernet.

“Their grazing activities helped to regulate algal abundances, reducing the competition with existing corals and clearing areas of the reef for new coral settlement,” says Smith.

“The role of herbivores is crucial in coral-reef environments as we transplant more coral back to the reef. The more grazers we have on the reef, the higher survival we will see in our transplants.”

Working with Mote Marine Laboratory, I.CARE has also experimented with the use of other herbivores in reef ecology systems.

“Restoration practitioners have put their full support behind projects to restore our herbivore populations to give our transplants their best chance, and I am really excited to hear about all the efforts going into restoring these urchins and the Caribbean king crab,” says Smith.

The Palmer Foundation has provided funding for the collection of adult king crabs from reef sites. “We bring them to Mote’s land-based facility, where they are able to reproduce and grow to a size where they can evade predation.

“Once we have the final permit from the Florida Wildlife Commission and the crabs have received a health-check, we will relocate them back to the reef in greater numbers and monitor their abundances and effects on competitive algae species.

“It is really exciting to be a part of restoring our entire reef ecosystem, which is something I have been passionate about since the beginning of my marine-science career.”

The little things

Recent observations of sea urchins offer hope of their recovery in south Florida, though not in the massive numbers that once menaced bathers and careless snorkellers or divers.

Harvesting spiny sea urchins is prohibited across Florida, and various counties have imposed total or partial bans on collecting other urchin species. Bag limits exist for some species, which must be maintained in live wells until landed. This limits numbers of these algae-eaters taken from the marine environment for food or for use in saltwater aquariums.

In nature it can be the little things that add up to the overall health of an ecosystem. In the case of humble sea urchins, their importance to coral reefs is absolute. As with everything in diving, the familiar instruction holds firm: look but don’t touch.

Also on Divernet: Can we eat our way through an exploding sea urchin problem?, Urchin killer sweeps down into Red Sea, Elephant seals dive asleep – and urchin death riddle solved, Blue Goos & urchins with hats – but why?