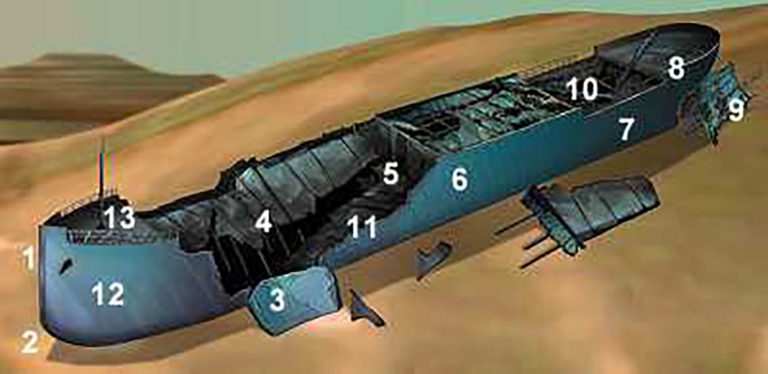

In the first of a major new series, JOHN LIDDIARD guides us round one of Devon’s most popular wreck sites. Illustration by MAX ELLIS

The British steamship Maine has been lying just over a mile off Bolt Head for 82 years now – in 30-35m of water, with its bows towards the shore across a strong current.

For several years its masts broke the surface and posed a hazard to mariners. The wreck has since been cleared to deck level, with most of the debris swept to its port side.

I used to like dropping a shotline just aft of amidships, where the wreck of the Maine is most intact. This would put the divers in about 30m of water on the deck. A swim to the stern and back and a quick once-round the engine room could be comfortably achieved in a 20-minute dive with minimal decompression.

This choice of location had as much to do with my shot-throwing accuracy as with anything. By aiming at the middle of the target, I was more likely to hit it!

Now I prefer to get the shot as close to the Maine‘s bows as possible. The first pair of divers down can loop it over a convenient bit of wreckage at the top of the bows, enabling divers to start and end their dives at the shallowest point of the wreck. This provides an ideal profile to get the most out of a dive computer and makes it easy to find the shot at the end of a dive.

With this in mind, I’ll start my tour of the Maine from the bows (1). Descend to the seabed here, looking back along walls of hydroids and plumose anemones and the shoals of fish that seem to gather by the bows of any large wreck (2).

One of the spectacular things about the Maine is that any part of it exposed to the currents is covered in plumose anemones. On a bright day in good visibility it is an incredibly pretty wreck.

At the sandy bottom, you can choose to follow either side of the wreck. Along the port side, you soon come to a break in the hull providing access to the remains of the forward holds (3).

This is where the torpedo hit and where the wreck is most broken up. I like to cross the hold here, past the remains of bulkheads and supports for the collapsed decking and through a swirling shoal of bib and poor cod.

The starboard side of the hull is more intact. Follow the seabed from the bows along this side and enter the hold through a large hole at the back of No 2 hold. This brings my two routes together on the starboard side beneath some collapsed deck plates just in front of the boilers (4).

If you like to explore inside wrecks, there is an easy route from here past the boilers and into the engine room (5), which is now largely open above. There are some girders to manoeuvre past, but you are never more than a few metres from an exit.

Going this way on one dive, I looked over to find a large conger eel swimming beside my head. After the initial shock, we looked at each other and continued side by side to the back of the engine room!

The next bulkhead is just a vertical skeleton separating engine room from fuel tanks. A short diversion here is to swim through the remains of the triple-expansion steam engine before carefully slipping through a gap in the bulkhead into the fuel tanks (6).

I like this part of the wreck for its eerie atmosphere, with a solid deck overhead and light entering only through the bulkheads at either end. Powerful dive lights illuminate a pair of colourful ladders in the middle of the tanks.

The aft holds are more intact and hence sheltered from the current. Life is less prolific. Exit is easily in reach through the large open cargo hatches, but the remaining decking is tight girderwork, with gaps too small for a diver to fit through.

The girders above are home to clumps of dead men’s fingers and the occasional sprig of red kelp. In the centre of the hold, the propshaft tunnel is broken open but access is prevented by silt and debris (7).

At the stern it is possible to ascend through the decks and cabins in the remains of the overhanging counter stern (8) to examine the steering gear, then look down to the seabed to view debris from the stern and the gun platform. If time permits, you can dip under the stern to check out the propshaft (9) – the prop has been salvaged.

By this point it is usually time to head back for the bows, unless you want to build up some heavy decompression. A fast scoot along the port railing past the remains of masts and rigging (10) brings me back to the engine room, where I can follow the collapsed plates (11) back to the forward holds and the bows.

Going forward past the breaks in the hull, it is possible to explore the largely intact No 1 hold (12) and ascend through the decks at the bows past winches and a huge anchor.

With the bows in just 18m, any time left can be spent hunting for nudibranchs and watching ballan wrasse peck at the hydroids (13).

Torpedoed in 1917

A torpedo from UC-17 hit the Maine on the port side just in front of the bridge on the morning of 23 March 1917, writes Kendall McDonald. At the time she was 13 miles south of Devon’s Berry Head, bound for Philadelphia. The blast blew the hatches off the holds, smashed the port gig and wrecked the bridge.

It also blew a great hole in her side through which seawater poured on to her cargo of chalk, horsehair and goatskins. Hoping he might beach her, Captain Bill Johnston sent distress calls and set course for the nearest land. The Maine was taken in tow when her engines stopped, but it was too late. The bulkheads gave way and at 12.45pm she sank ‘gracefully, upright and on an even keel’ within easy reach of Salcombe.

The 3616-ton Maine was launched as Sierra Blanca in 1905 and was 114m overall with a beam of 14m. She was renamed in 1913. The wreck was swept of her superstructure in 1920.

She was bought for 100 in 1961 by Torbay BSAC Branch, which sold her bronze propeller for £840. The 12cm gun on her poop was removed by unofficial salvors later.

Despite being explored by thousands of divers, her 35kg solid brass bell was not found until 1987 – by two divers paying their first visit!

FACT FILE

How to find it: GPS 50.12.820 N, 3.51.045 W (degrees, minutes, decimals). The Maine is easy to find from transits, but beware: a number of guidebooks show the drystone wall above the Ham Stone going in the wrong direction.

Tides: On spring tides it is essential to dive at slack water, two hours after high or low water at Devonport. On a good neap an experienced diver can haul down a shotline against the current and hide inside the wreck, a strategy feasible from an inflatable or RIB but unlikely to be practical from a hard boat.

Getting there: M5 and A38 towards Plymouth. Left on A381 to Totnes, Kingsbridge and Salcombe. For Hope Cove take sharp right at Malborough village just before Salcombe.

Diving and air: Pat Dean runs mv Lodesman with onboard compressor and can provide full package with accommodation ashore. If taking own boat, Lodesman can provide air fills at arranged rendezvous such as slip in Salcombe (01548 843319). Diventure at Salcombe runs RIB shuttle and offers air and nitrox fills (01548 843663), www.diventure.demon.co.uk. Some Plymouth and Dartmouth boats also venture as far as Maine. Try Mount Batten Dive Shop, Plymouth (01752 405403)

Launching: At Salcombe the slip at Shadycombe car park is usable throughout the tide. It is expensive for a weekend but can be economical for a week or two, and is best suited to large RIBs. A slip at Hope Cove (Inner Hope) has a reasonable launch fee and is wet for just an hour or two either side of high tide. Below the slip is a firm, sandy beach suitable for launching with a 4×4 when the slip is dry.

Accommodation: The Lobster Pot Inn at Hope Cove is diver-friendly (01548 561214). There are many hotels, B&Bs and campsites in the area. Contact Tourist Information on 01548 843927. Further details on Salcombe Online

Qualifications: Best suited to reasonably experienced sport divers and above. It is not a dive for novices or newly qualified divers.

Further information: Admiralty Chart 1613, Eddystone Rocks to Berry Head. Ordnance Survey map 202; Torbay and South Dartmoor Area. Dive South Devon by Kendall McDonald; The Wreckers Guide to South Devon Vol 2, by Peter Mitchel.

Pros: Spectacular wreck that is reasonably intact and not too deep. Short boat ride from Salcombe or Hope Cove. Many inshore wrecks available for second dive.

Cons: Strong tides. Exposed to any heavy sea from the west through south by south-east.