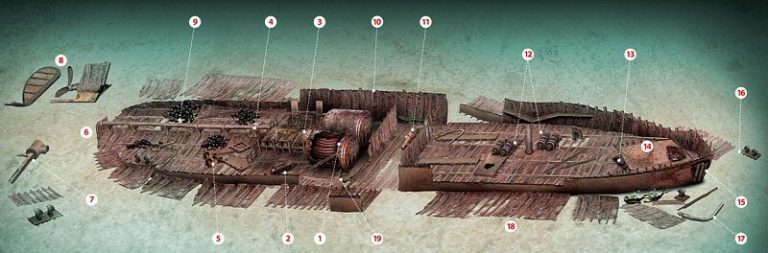

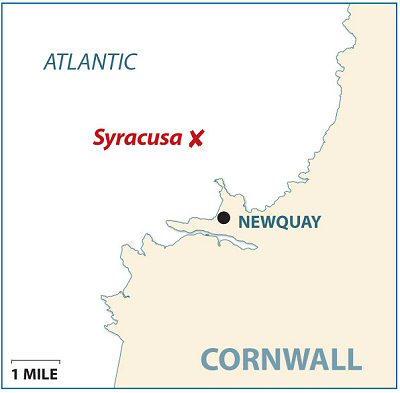

This steamer, wrecked 112 years ago off Newquay, is justifiably popular – but make sure conditions are right before diving it, warns JOHN LIDDIARD. Illustration by MAX ELLIS

EVERY SECTION OF COASTLINE has its signature wreck. It’s the one that everyone dives either for its splendour as a wreck, its convenience, or just because it catches the diving imagination. From Newquay this wreck is the Syracusa, a 1234-ton steamship that foundered in 1897.

The wreck has been salvaged and decayed close to the 34m seabed, so our tour begins at the highest point of the wreck by the boilers (1), the tops of which come to just shy of 30m.

The port boiler is pretty much intact, while the starboard boiler is opened up to display a tangle of boiler tubing.

Just aft of the starboard boiler, a small single-cylinder steam engine would have driven a pump (2).

The top of the main triple-expansion steam engine (3) has fallen to starboard, leaving the connecting rods twisted over and the port side of the supporting struts for the engine remaining upright.

Behind the engine, the crankshaft is still connected to the thrust-bearing (4), with the propeller-shaft emerging from the remains of the engine-room bulkhead and continuing sternwards.

Staying on the starboard side of the ship, a cargo winch that would have served the aft holds is broken with the base upside-down, then the spindles spread next to the base (5). The sides of the hull have fallen outward to the seabed, leaving just a hint of where the original outline of the hull rises.

The hull soon begins to narrow for the stern, with a pair of bollards fallen from a long-decayed but still upright deck just inside the hull. Coal remaining from the cargo is scattered nearby.The hull ends with a break in the propeller-shaft (6).

A few metres off the stern, and a little to starboard, lies the top of the rudder-post and the steering mechanism (7), an interesting dustbin-shaped casing that would have contained the gearing to turn the rudder-shaft through rotation of a horizontal steering-shaft.

A little further out, and off to port, is the tail section of the keel, with the last section of propeller-shaft, the stern gland and the propeller (8). Behind this is the rudder – perfectly positioned relative to the propeller, but with the top of the shaft bent over by almost 90°.

This suggests that the Syracusa went down stern-first with the tide running, so that the rudder and propeller caught on the seabed and were wrenched from the ship as it settled with the tide.

Now, following the propeller-shaft forwards, count the bearing blocks that support it above the keel. Just after the third block forwards from the stern, and partly hidden beneath the shaft, is a large ring spanner (9), sized to fit the big nut that holds the propeller on the end of the shaft.

With such a spanner carried, I would also have expected the Syracusa to have been carrying a spare propeller, but I failed to find it. Perhaps it is partly buried in debris somewhere, perhaps it was salvaged, or perhaps the Syracusa was already running on its spare.

The port side of the hold contains a further scattering of coal from the cargo. Then, as we near the engine-room bulkhead, the port side of the hull remains intact and rises to main deck level (10).

This continues past the boilers, then drops to the seabed again where the side of the hull has fallen outwards.

A pair of bulkheads crossing the wreck here marks the bunker space, where the coal for fuelling the ship’s boilers would have been held. In the middle of this space and towards the forward bulkhead is the helm and steering-engine (11), fallen from the wheelhouse that would have been above this part of the ship.

Forward of this bulkhead and along the hold, a pair of winches (12) rest upright on either side of the mast-foot that stands from the keel. Off to the port side, the side of the hull is again intact, with even a scrap of the main deck supported by it, though drooping slightly.

Continuing along the forward hold, the anchor-winch (13) has fallen to rest across the keel. The starboard side of the bow has fallen inwards (14), while the port side of the bow has fallen outward to rest on the seabed.

Right at the tip of the bow, it is broken down almost to the keel (15). A pair of bollards (16) stand upright on the coarse granite sand a couple of metres out to port.

A similar distance off to starboard is a small derrick (17). This would originally have been located in the centre of the bow deck, and used for lifting anchors onto the deck after the anchor-winch had raised them.

Our route back to the boilers and the shotline follows the broken starboard side of the hull (18). Just before arriving back at the boilers, a fallen plate has a small valve wheel on it (19). Any time remaining before ascending the shotline can be spent looking for conger eels among the tubes of the starboard boiler.

RAGEDY OFF NEWQUAY

THE SYRACUSA, cargo steamer. BUILT 1879, SUNK 1897

THE 1243-TON SCHOONER-RIGGED iron-screw steamer Syracusa was built in 1879 as the Bavaria at the Flensburger Geschaft for the Hamburg-Amerika line, writes Kendall McDonald.

It wasn’t until she was sold to Robert Sloman of Hamburg a few years later that she became the Syracusa, sailing under the German flag with her home port listed as Hamburg. Her captain then was Karl Rendey, and his 24 crew were regulars on all his voyages. They would all be killed together when the Syracusa was wrecked on 6 March, 1897.

The voyage on which she was smashed to pieces was one they had undertaken many times before. The vessel’s holds were full of Welsh coal from Newport to be delivered in Naples.

First to spot “a large foreign-looking steamer” in trouble was Newquay Coastguard. Syracusa seemed unable to make headway when she was five or six miles off the coast, and at 4pm, when she was four miles NNW of Towan Head, she began firing distress rockets.

Five minutes later, the crew of the lifeboat Willie Rogers were called, and within 30 minutes she was afloat. The weather was so bad off the headland that the Willie Rogers was twice beaten back, and almost wrecked in the harbour mouth. Her cox’n was badly injured before nearly 100 fishermen dragged her to safety. The Syracusa had by then drifted five miles, listing heavily to port.

The gale now increased until coastguards, rocket crews and spectators had to crawl on hands and knees across Towan Head. At 11pm, three bright flares went up from the Syracusa; then the dark was unbroken. It was assumed from this that the ship had foundered.

The Willie Rogers launched again, heading now for the great cliffs north of Newquay. It came across the wreck of a ketch, but had no way to stop it capsizing. It was smashed to fragments, and the three men aboard were all killed.

In the dawn, the Syracusa’s topmasts were found jutting out of the waves some 300m from Towan Head.

Wreckage, tons of coal, a boat bearing the vessel’s name, and 25 lifebuoys, each bearing a different man’s name, were washed ashore.

TOUR GUIDE

GETTING THERE: Follow the M5 to Exeter, take the A30 past Bodmin to Indian Queens, then turn north on the A392 to Newquay.

HOW TO FIND IT: The Syracusa lies just out of Newquay at 50 26.33 N, 005 06.64W (degrees, minutes and decimals). The bow is to the east and the wreck rises 5m from a 34m seabed at high water.

TIDES: In the big tides of North Cornwall, slack water is essential. It occurs at high- and low-water Newquay, with the low-water slack being considerably shallower.

DIVING & AIR: Atlantic Diver, skipper Chris Lowe, 01637 850 930. Nitrox, oxygen and trimix are available, but check in advance to make sure that sufficient gas is in stock.

ACCOMMODATION: Chris Lowe can provide bunkroom accommodation. There are plenty of other options in Newquay.

QUALIFICATIONS: Suitable for PADI Advanced Open Water Diver/BSAC Sports Diver. A good wreck on which to take advantage of nitrox.

LAUNCHING: Slip at Newquay.

FURTHER INFORMATION: Admiralty Chart 1149, Pendeen to Trevose Head. Ordnance Survey Map 200, Newquay, Bodmin & Surrounding Area. Shipwreck Index of the British Isles, Volume 1, by Richard & Bridget Larn. Dive The Isles of Scilly & North Cornwall, by Richard Larn and David McBride.

PROS: An easy and enjoyable wreck that is reasonably accessible. It usually enjoys cracking visibility.

CONS: Big tides make timing of slack water critical.

DEPTH RANGE: 20-30m

Thanks to Chris Lowe.

Appeared in DIVER June 2009