A treat for technical divers is the dive-site JOHN LIDDIARD has chosen for our 150th Wreck Tour. This Norwegian coaster was a collision victim off south-eastern Scotland in 1917. Illustration by MAX ELLIS

I WAS UNDECIDED just what to call this month’s wreck of a small coaster. It was first identified as the Ferrum from a bell dated 1896, but no ship of this name was listed.

Then a two-krone coin was found showing King Haakon VII of Norway, giving both a Norwegian connection and a date for the coin of between 1908 and 1917.

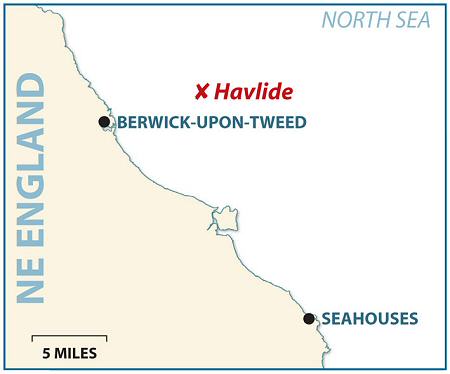

Finally, Ron Young tracked it down as being named Havlide at the time it sank, the Ferrum having been sold to a small Norwegian shipping company of the same name in 1898. But alternative names don’t stop there, as it is listed as Havilde in Hydrographic Office data.

We know what it is, a coaster of 425 tons – I am just undecided what to call it. I have it written up as the Ferrum in my logbook. I originally labelled my sketch of the wreck as the Ferrum. However, I suppose Havlide is more in keeping with the way we generally name wrecks, as that was the name at the time of sinking.

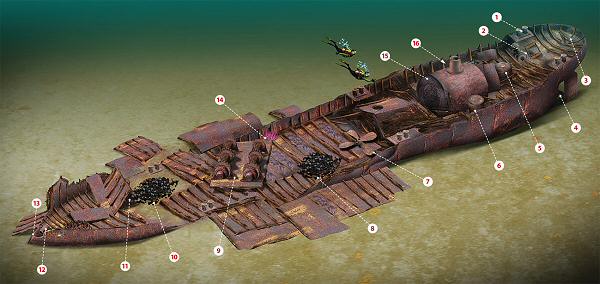

At the time I dived the Havlide, Andrew Douglas, skipper of Sovereign III, conveniently hooked the shot across a pair of bollards to the starboard side of the stern (1).

While the Havlide is small enough to swim its length and back in a single dive, we didn’t know that at the time. Hooking the shot at the stern would have enabled us to see the wreck by swimming a single length of it.

To the centre of the deck at 56m is a small winch and the coaming from a hatch (2). This area of the ship would have been crew accommodation, so the hatch would most likely have had wooden steps leading down below it.

The winch would have been used for hauling mooring lines, or perhaps for a small kedge anchor, or maybe even to raise a small mizzen sail.

While steam was the power of choice, ships of this era were often constructed so that they could also use sails.

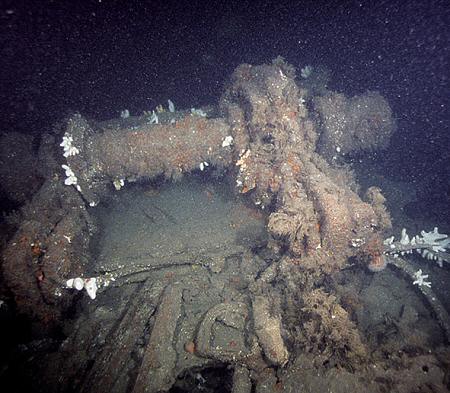

Although the deck is collapsing, overall it is intact. To the aft the rudder-post is topped by a simple T-bar steering mechanism (3).

Dropping over the stern, the rudder remains in place, as does a four-bladed iron propeller (4). Both are liberally sprinkled with small white anemones and clumps of dead men’s fingers. The seabed is at 60m.

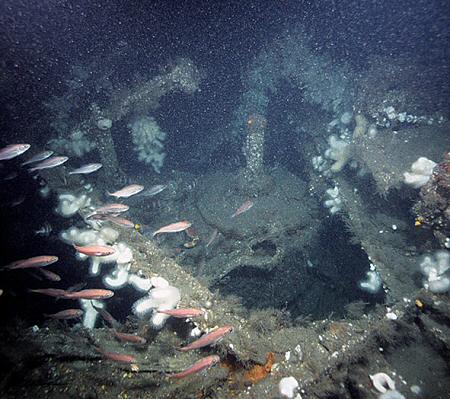

Back on the deck, the small triple-expansion steam engine (5) pokes out of a maze of debris. The low-pressure cylinder is easily visible, with the intermediate and high-pressure cylinders being better hidden.

Staying towards the port side of the wreck, an upright water tank (6) stands between the Havlide’s single boiler and the side of the hull.

The wheelhouse would have stood high in front of the boiler, but was largely built of wood, so has now rotted away and collapsed into the hull. Immediately forward of the wheelhouse debris and resting on the floor of the hold is a spare propeller (7).

The sides of the holds have collapsed out to leave the holds almost level with the seabed. A small pile (8) is all that remains from the cargo of coal, on the way to Norway, which was the Havlide’s regular route.

As with most ships of this size, the Havlide had two forward holds. The general arrangement of masts and winches varied, but on the Havlide it was obviously a single mast between the holds, with derricks extending forward and aft, all served by a pair of winches (9). These are still attached to a deck-plate, but now fallen and askew to the line of the ship.

The slightly smaller forward hold also contains a small pile of coal (10). There are pairs of bollards to either side of the deck, and then we come to the forecastle. Unlike the stern, this is broken down almost to the seabed.

The small anchor-winch (11) has fallen backwards on its deck-plate. To the port side, a pile of chain remains from the chain-locker and leads to a hawse-pipe (12) on the port side of the bow.

Perhaps there is a corresponding starboard hawse-pipe among the debris, or perhaps there never was one, and the Havlide was fitted with only one anchor.

The stem of the bow (13) is upright, but broken down almost to the seabed. Such damage to the bow of a small wreck is often caused by a trawler, so perhaps the starboard hawse-pipe and anchor-chain has been dragged away in a trawl, possibly with the anchors, which are also missing.

Despite the depth, the Havlide is a small wreck, so most divers will have time to return to the stern along the port side rather than ending their dive at the bow. Passing the winches between the holds, a large anemone is sheltered beneath the end of the forward winch, next to a section of the steam-pipe (14) that would have powered the winches.

Passing along the starboard side of the boiler (15), pipes lead off from the upright steam-drier at the top.

Behind the boiler and starboard of the engine are a toilet and basin and the remains of a black-and-white tiled floor (16) – the traditional tile pattern for a British ship. As the Ferrum, the Havlide was originally registered in West Hartlepool.

It was also in this part of the wreck that the coin that provided a clue to the origin of the vessel was discovered.

With a long decompression ahead, the tide will soon be ripping along the shotline.

Either a delayed SMB or detachable lazy shot or decompression station will be needed for the ascent.

COLLATERAL DAMAGE

THE HAVLIDE, coaster. BUILT 1892, SUNK 1917

The loss of the Havlide took place on 16 March, 1917, not by torpedo or gun, but by collision with HMS Torpedo Boat 94, some four miles east-north-east from Berwick lighthouse, writes Kendall McDonald.

The coaster was carrying coal to Skien in Norway as part of a convoy sailing between the Tyne and Lerwick. The British torpedo boat was part of the convoy escort.

The Havlide was launched as the Ferrum at West Hartlepool in 1892, where she was registered. The 47m ship was powered by a 55hp three-cylinder engine that used one boiler.

She had an iron deck, a well-deck, a quarter-deck, a budge-deck and forecastle. From 1898 her name was changed to Havlide, and with Havlide of Skien in Norway being the registered owner, this was not surprising.

Some time after the collision, the bell, clearly marked Ferrum and 1892, was found by two divers and lifted. Today, it has disappeared!

TOUR GUIDE

GETTING THERE: From the south, follow the A1M and A1 north, then take the B3142 to Seahouses. From the north turn off the A1 on the B3140 to Bamburgh and continue along the coast to Seahouses. Once there, just follow your nose to the harbour.

HOW TO FIND IT: The GPS co-ordinates are 55 48.144 N, 001 50.708 W. The wreck stands 4m from a 60m seabed, with its bow to the south.

TIDES: Slack water is essential, and occurs approximately 2hr 30min after high water and low water Seahouses. Low water slack is obviously the better time to dive a wreck this deep.

DIVING & AIR: Sovereign Diving, 01665 720760.

ACCOMMODATION: B&B with Sovereign Diving.

LAUNCHING There is a slip in the harbour at Seahouses.

QUALIFICATIONS: Normoxic trimix.

FURTHER INFORMATION: Admiralty Chart 160, St Abbs Head to the Farne Islands. Ordnance Survey Map 75, Berwick-upon-Tweed & Surrounding Area. Tourist Information, 01289 301777, Visit Northumberland.

PROS: An ideal wreck for those just getting started in trimix diving.

CONS: Too deep for many divers

DEPTH: 45m+

Thanks to Andrew Douglas, Ron Young and Mike Atkinson.

Appeared in DIVER June 2011