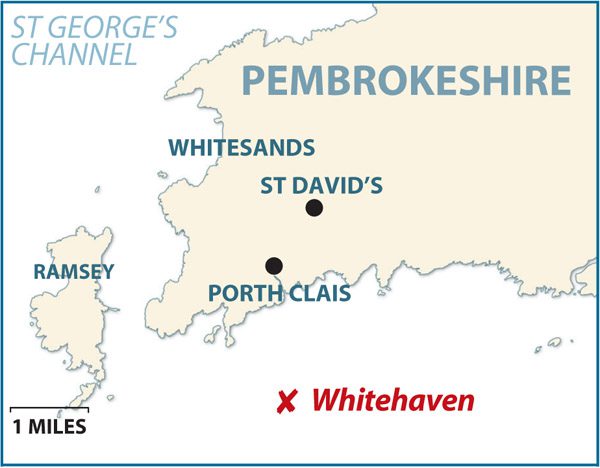

We have a double-header for you to enjoy this month – two small vessels sunk within 10 years of each other in the mid-Victorian era off Pembrokeshire. JOHN LIDDIARD leads the tour, with MAX ELLIS providing the illustrations

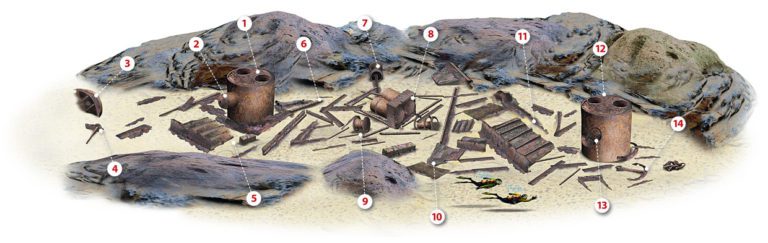

OUR SECOND Pembrokeshire mini-tour is of the 232-ton paddle-tug Whitehaven, which again foundered in calm conditions, this time just out of the southern end of Ramsey Sound. The wreck lies along a gully with the boiler tipped on end (1).

Skipper Mark Deane, assisted by Bob Lymer, had previously tied a small buoy to it, so we wasted no time finding the wreck.

Down the side of the boiler, a steam reservoir and dryer (2) points roughly aft.

Wreckage is now loosely scattered across the rocky gully all the way to a small section of the stern (3), with a hole through it where the rudder would have been fitted.

The top of the rudder-post with the tiller arm still attached lies just off to one side (4). This is the deepest point of the wreck at 18m on low-water slack.

Heading forwards again, the larger sections of wreckage are to the starboard side of the boiler (5).

However, moving across to port just forward of the boiler reveals a section of steam-pipe (6) leading forward towards the engine.

The first sign of the moving machinery is a shaft and hub of the port paddle-wheel (7), still connected by a section of the crankshaft and connecting rod to the two-cylinder compound engine (8).

This was inclined and mounted forward of the paddle-wheels; the wedge-shaped supports are still visible beneath it.

The hub of the starboard paddle (9) is broken from the shaft and lies next to the engine.

The orientation of the engine has led some divers to think that the end we have just visited is the bow.

With paddles, there is no need to mount boilers forward of the engine because there is no shaft leading aft to a propeller.

Continuing forward, the remains of a bulkhead (10) span the width of the wreck. A little further forward and angled across the starboard side of the wreckage is a section of mast (11).

As the wreck narrows, our tour comes to the second boiler (12), again tipped up with furnaces uppermost and the steam dryer (13) sticking out to starboard.

Bearing in mind the weight of water in a boiler, putting one boiler to either end with the engine in the middle would have given a nicely balanced hull with room for a small hold next to the engine.

Having seen sections of the steering at the stern, final proof that this is indeed the bow is a small Admiralty-pattern anchor (14).

MORE POOR NAVIGATION

THE WHITEHAVEN, paddle-tug. BUILT 1875, SUNK 1879

THE PRACTICALITY OF RUNNING commercial sailing ships was extended by the use of steam tugs to tow them in and out of harbour and in coastal waters at either end of their voyages. Long after screw propulsion became the norm, tugs continued to be built with paddle-wheels for manoeuvrability.

On a ship as small as a tug, it was practical for the paddle-shaft to be built with a clutch, enabling a paddle-tug to turn about its own centre. Sail and paddles, two outdated technologies, extended their working lives together.

The 232-ton iron paddle-tug Whitehaven was one of a succession owned by the Trustees of Whitehaven Harbour in Cumbria. It was built in 1875 by the Whitehaven Shipbuilding Co, with 80hp compound machinery by Rankin & Blackmore of Greenock.

A specialist in paddle-engines, Rankin & Blackmore later built the one that drives the Waverley, a paddle-steamer that still operates passenger trips today.

On 21 May, 1879, the Whitehaven was on passage from Liverpool to King Road, at the mouth of the River Avon in the Bristol Channel. Captain James Hodgson and his crew of 10 had 12 passengers on board.

The sea was calm but it was foggy when, heading down Ramsey Sound, Captain Hodgson’s attention was called to a ripple sea some 150m ahead. Although aware of the danger of Horse Rock, Hodgson took no avoiding action, thinking the ripple to be part of the tidal race at the end of the sound.

At 10am the Whitehaven struck, then continued with the tide to sink off Porth Clais. The court of enquiry attributed the loss of the Whitehaven to careless navigation, and suspended Captain Hodgson.

TOUR GUIDE

GETTING THERE: Follow the M4 and A40 to Haverfordwest and on to St David’s. Porth Clais is signposted from there.

HOW TO FIND IT: GPS co-ordinates are 51 50.876 N, 005 16.790 W (degrees, minutes and decimals). The wreck lies in gullies and it can therefore be difficult to find. Its position is about 700m to the south of Half Tide Rock. A small buoy may be attached to the boiler. If not, it may be necessary to drop a shot on the GPS co-ordinates and make an underwater search.

TIDES: Slack water is approximately two hours after low-water Milford Haven. Experienced divers may be able to dive the wreck off-slack on a neap tide.

DIVING & AIR: Celtic Diving operates hardboat charters on Wandrin’ Star out of Fishguard Harbour, 07816 640684. The closest source of nitrox is Old Mill Diving Services near Milford Haven, 01646 690190.

ACCOMMODATION: B&B through Celtic Diving at Pwll Dewi.

LAUNCHING Launch over the slip and beach at Porth Clais. The slip is wet only at the top of the tide.

QUALIFICATIONS: Entry-level (at low water slack).

FURTHER INFORMATION: Admiralty Chart 1482, Plans in South West Wales. Ordnance Survey Map 157, St David’s & Haverfordwest Area. Fishguard tourist information, 01348 872037.

PROS: An unusual opportunity to dive a paddle-tug.

CONS: Difficult to find, as it lies among rocky gullies.

DEPTH: -20 m

Thanks to Bob Lymer, Mark Deane, Jim Hopkinson & Ron Young

Appeared in DIVER March 2012