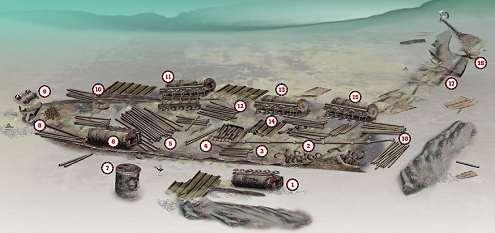

Calling all train-spotters, grab your tanks and slates and head for the West Country! There’s a wreck down there you have to see, says JOHN LIDDIARD. Illustration by MAX ELLIS

THIS MONTH’S WRECK IS A MUST for bobble-hats and anoraks because the St Chamond off Cornwall’s north coast has more steam locomotives on it than any other wreck I know. Some records list five locomotives carried as deck cargo but, on my dive, I counted six, and local skipper Dougie Wright is confident that there are at least seven. I compared notes with him after my dive and know where I missed one, but more on that later.

The St Chamond is another U-boat victim of World War One, torpedoed and sunk just 1.5 miles off St Ives on 30 April, 1918.

As I descended, my first sight was of a locomotive lying on its left side with the shotline draped over it (1). It’s not really surprising that the mechanical parts of a steam loco are so similar to the equivalent parts of a steamship – a cylindrical boiler containing the firebox and lots of hollow tubes, with pistons driving the wheels rather than a propeller-shaft.

In the case of the locos on the St Chamond, there are four large driving wheels on each side and two pairs of smaller wheels forward of the drive wheels.

The main body of the wreck lies a few metres from the chassis of this locomotive, largely flattened to the seabed with just a few scraps of hull rising upwards. Cargo in this area is mainly steel hoop “tyres” for the loco wheels and couplings for the main cargo of pipes (2). The rest of the cargo seems to have comprised largely steel pipe, clusters of which can be found all over the wreck.

Towards the centre of the ship, the propeller-shaft lies exposed (3), the only traces of the tunnel being a few curved ribs of steel. It is hard to tell on a wreck this broken, but my impression is that the shaft has shifted slightly off the centreline to port.

Moving forward, the remains of a triple-expansion steam engine are spread to starboard from the crank (4).

Further forward along the centreline of the ship is a large pile of steel pipes (5). Skirting this mountain to port, another steam locomotive lies on its side (6), this time within the outline of the St Chamond’s hull.

The St Chamond was fitted with two boilers. One of these is standing upright just off the port side of the wreck (7), but I could find no sign of the other boiler there. At only 20-24m deep, and exposed to the full force of Atlantic storms, it could easily have been rolled well clear of the wreck or broken into scrap and buried.

Continuing to follow the port side of the wreck forwards, the bow is marked by a pile of anchor-chain and a pair of anchors still tight in their hawse-pipes, the hull having disintegrated about them (8).

The anchor-winch has fallen forward and can be found a few metres off the tip of the bow and slightly to starboard (9). This is the shallower end of the wreck, being about 20m deep at low water.

Following the starboard side of the wreck back, a steel dome (10) has me puzzled. I thought at first that it could have been from the front of one of the locomotives, but it’s a bit big for that.

It is also on the large side for the remains of a condenser casing left here when the non-ferrous metals on the wreck were salvaged, and perhaps a bit robust for a simple water-tank. Possibly it is simply the remains of an item of cargo.

A little further back are a pair of locos. The chassis of one stands upright with the boiler completely gone, while a second rests on one side alongside it (11). It is here that Dougie Wright has seen a third loco outside and hidden behind this pair from the point of view of my sketch.

Either I missed it when diving the St Chamond or perhaps it has been broken up or shifted away from the wreck by a storm since he last dived the wreck several years previously.

Continuing aft on the starboard side, another small pile of steel pipe (12) rests approximately level with the remains of the engine.

A fifth loco lies pointing aft, reasonably intact but tipped just outside the outline of the hull (13). Inside this, a pair of broken winches lie along what I would consider to be the centreline of the ship (14). The propeller-shaft has probably shifted slightly off that line to port.

The sixth locomotive (15) lies a little further aft, in a similar orientation to the previous one. Dougie’s experience is far more comprehensive than mine, though it is a few years since he last dived the wreck. Perhaps the original manifest was wrong or badly written, or perhaps space was found to load one or two extra locos at the last minute. Either way, I am confident that there are more than the recorded five.

The wreck soon fizzles out with another small pile of steel pipe from the cargo (16). There are a few scraps of wreckage spread out aft of this point across a pebbled seabed, with some rocky ridges at a low-water depth of 24m.

The remains of the stern are well off to starboard. A section of propeller-shaft projects from a small V-section of the keel (17), leading to a steel propeller partly buried in the seabed. Just aft of this, the remains of the rudder rest on the bottom (18).

TRAIN SET DERAILED

Getting troops, ammunition and other supplies from the French ports to the trenches of the Western Front, ready for the “Big Push” against the Germans planned for summer 1918, was a nightmare for British Army planners. They soon found out that the French railways couldn’t cope with the tons of extra war material needed to be stockpiled behind the Allied lines, writes Kendall McDonald.

The track was there, or lines could be relaid, but nearly four years of war had played havoc with the engines and rolling stock. The only thing to do was to ship over British steam locomotives to pull the wagons. And that’s what they did.

In the case of the 3,077-ton French steamer St Chamond, five 75-ton British steam engines were documented as being loaded aboard as deck cargo at Glasgow before she set out to carry them to St Nazaire at the end of April 1918. However, there might have been some last-minute additions.

On 30 April, within a mile of Cornwall’s north coast, near St Ives, the 94m-long St Chamond was unfortunate enough to steam into the periscope sight of U60, commanded by Oberleutnant Schuster, who had already sunk 40 ships with this same U-boat of the Second Flotilla of the High Seas Fleet.

Schuster made no mistake in sinking his 41st victim with one torpedo, though Capitaine Doln and his crew abandoned ship without loss.

GETTING THERE: Follow the M5 to Exeter, then the A30 to Hayle. Enter Hayle from the Penzance end of town and turn back along the rough ground at the west side of the harbour as the road crosses beneath the railway viaduct.

DIVING AND AIR: San Pablo III, skipper Dougie Wright. Bill Bowen runs a fast compressor on the pier at Penzance.

ACCOMMODATION: Dougie Wright can arrange stays with local B&Bs. There are also many camping and static caravan-sites in the area. Penzance Tourist Information can provide a list.

TIDES: There is a big tidal range along this coastline and consequently some strong currents. Slack water occurs at high water and low water Hayle.

LAUNCHING: There are a number of slips in Hayle. If you don’t know the area, be very careful coming back in across the Hayle sandbar. It can be difficult to distinguish the safe channel among the breaking surf. Bear in mind that the harbour is inaccessible for a couple of hours either side of low water.

HOW TO FIND IT: The listed position is 50 14.50N, 05 29.54W (degrees, minutes and decimals). The surrounding seabed is pebbles with low ridges of rock. The St Chamond’s bows point to the north-west, with the highest points on the wreck being the loco boilers rising just a couple of metres above the seabed.

QUALIFICATIONS: Shallow enough for most divers.

FURTHER INFORMATION: Admiralty Chart 1149, Pendeen To Trevose Head. Admiralty Chart 1168, Harbours On The North Coast Of Cornwall. Ordnance Survey Map 203, Land’s End, The Lizard And The Isles Of Scilly. Penzance Tourist Information.

PROS: An unusual cargo at a shallow enough depth to be able to tour the entire wreck without requiring excessive decompression.

CONS: A tidal entrance to the harbour at Hayle restricts departure and return times. The site is exposed to a big Atlantic groundswell.

Thanks to Dougie Wright, Alex Poole, and members of Penzance BSAC.

Appeared in Diver, April 2002