A great British favourite finally gets its turn in the spotlight this month, as JOHN LIDDIARD looks at a liner that sank during WW1 off Swanage laden with perfume, watches, champagne – and lots of brass. Illustration by MAX ELLIS.

Take a trip to the busy seaside town of Swanage on the Dorset coast and your immediate diver’s observation will be that two dive sites dominate the local diving scene. There’s under the pier, and there’s the wreck of the liner Kyarra.

Swanage Pier has a reputation as one of the best shore dives on the south coast, and the Kyarra is justifiably a very popular wreck. If you have already dived it you will know what I mean, and if you have not, then there is no doubt it’s about time you did.

The wreck is 126m long, but at an ideal depth for getting the most out of nitrox. Pick the right mix and it is possible to tour the entire length in a single dive without feeling rushed, and still have time to make some excursions away from the deck.

But it is a big ship and there will be plenty left to see on future dives.

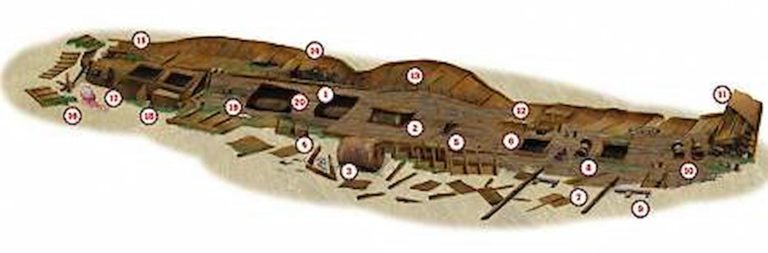

A dive on the Kyarra usually begins amidships on the port railing (1) because that is where a buoy is invariably tied on to the wreck.

The wreck lies on its starboard side, with the port railing uppermost at about 23m. With the deck below you and the railings on your left, you will be facing forwards.

Heading this way, a large opening in the deck precedes the boilers. This area has broken open, leaving a boiler poking out through the wreck (2). Another boiler (3) has rolled clear of the wreck before the hull and deck collapsed over the boiler room.

The fire holes are at the front and top of the boiler, showing that it has rolled just over 90’s?, as the wreck is already resting on its starboard side.

The Kyarra had four boilers, which leaves two more buried inside.

Just behind this boiler (4) is an area of the wreck in which crockery has been found buried in the silt.

Moving a little further forward past some upright ribs and a split in the wreckage (5) provides a way into the front of the boiler room.

In the past I have travelled from the opening by the first boiler (2) right through the boiler room, exiting through this split (5), though the wreck has now decayed to the point where I don’t think this is any longer possible.

Continuing forward, the deck has collapsed almost flat with the seabed.

The remains of teak decking are broken by the surround from a hold with an upside-down winch just to port (6). This is one area of the wreck in which perfume bottles have been found.

The wreck gets quite confused from here forwards. The easiest way to find the bow is to follow the starboard side of the wreckage past a collapsed mast and boat derrick (7).

A hold opening just forward from the foot of the mast (8) leads to an area in which cases of pocket watches have been located.

Just past a second derrick (9), the anchor winch is still attached to a strengthened area of bow deck (10), though it is partly broken. A section of chain trails forwards through the end of a hawse pipe and disappears below the wreckage.

The depth here is about 32m.

The upper part of the bow has broken, leaving just the leading edge and a few ribs sticking up.

Lower down, a substantial section of the bow is intact and resting on its starboard side, the port side rising 4 or 5m above the seabed (11).

Finding the way back along the wreck can be confusing, especially in poor visibility. Ideally I would aim to follow the line of the port side of the deck until the wreck regains some shape and the railing is again intact (12).

In the past, I have ended up thinking I was following a straight line but actually swimming in circles back to the bow.

A diversion towards the keel of the wreck from here shows that the port side of the hull has collapsed into an inverted W-shape (13).

Further aft in the valley of the W, the remains of one of the Kyarra‘s two engines pokes through the side of the hull (14).

The propeller shaft leads to the stern, appearing and disappearing beneath plates of wreckage (15).

The stern used to be fairly intact, but has recently broken off to leave debris on the seabed, with the rudder, rudder post and steering gear separated cleanly from the rest of the wreck just off the stern (16).

Moving forward again, the port side of the wreck has collapsed, with the remains of a winch and a large capstan almost at the stern (17).

Next come the hatches from another two holds (18) and a large capstan set in the deck (19). You may find little puddles of silver on the seabed in this area – liquid mercury spilled from the cargo.

A large hole in the deck (20) would have been the main ventilation area above the engines. It is a bit of a squeeze, but it is possible to swim through from here to behind the boilers (2).

Access to the engines is blocked by the collapsed port side of the hull and the way further back inside the wreck is through a tangled mess of debris.

With the site being quite busy, skippers generally prefer divers to release a delayed SMB rather than crowd the line and possibly pull the buoy under.

Thanks to Richard ‘Titch’ Titchener, Peter Williams, Nick Herbert and Dorset Divers.

THE ‘SHIP MADE OF BRASS’

‘The ship that was made of brass’ was what they called the 6953 ton Kyarra, a twin-screw passenger and cargo liner, 415ft long with a beam of 52ft, when she was launched by Denny Bros in Dumbarton on 2 February, 1903.

And it is true that anything aboard her that could be was made of brass, writes Kendall McDonald. From stem to stern, her portholes were heavy brass and her interior and exterior fittings solid brass, as were door handles, navigation lamps, nameplates and even the end-supports of the benches on her decks.

The Kyarra was registered in Freemantle before WW1, and plied the England-to-Australia run for the Australasian United Steam Navigation Co.

In the war, she did the same thing as well as helping to land Anzac Expeditionary troops in the Dardanelles.

In 1917 she became a casualty clearing ship, and had a 4.7in quick-firing gun mounted on her stern as a defence against U-boats.

But it would not help her when she sailed from Tilbury on her last voyage on 24 May, 1918.

She had been ordered to embark 1000 war-wounded Aussie soldiers in Devonport and return them to Sydney. She was also to carry some civilian passengers and a full general cargo.

In the early morning of 26 May, the Kyarrahad cleared the Isle of Wight and was moving fast through calm seas around Anvil Point.

Captain William Smith didn’t know it, but German submarine ace Oberleutnant Johann Lohs was watching him through the periscope of UB-57.

Lohs was having a good mission out of Zeebrugge. Two days before, he had sunk the P&O liner Moldavia, converted to an armed merchant cruiser.

This time he used a torpedo to hit the Kyarra in her port side amidships, killing six crew. The rest took to the lifeboats. Seven minutes later the Kyarra nose-dived under.

Ron Blake and his wife Linden were the next to see her when they dived an obstruction they thought was a reef in 1966. A year later their club, Kingston BSAC, bought the ship for £120, though not the mixed cargo, valued at £1500 when she sank.

Since then thousands of divers have put the Kyarra in their logbooks.

And they have discovered just how mixed her cargo was – bottles of champagne, red wine, beer and vinegar, bales of silk and cloth, French perfume, lino, sealing wax, medical supplies, cigarettes, silver purses, men’s big pocket watches, ladies gold wrist-watches and, of course, masses of brass.

TOUR GUIDE

GETTING THERE: Follow the A351 past Corfe Castle to Swanage and follow the signs for the town centre and pier. Parking on the pier is limited, so be prepared to drop divers and kit and use the car park further up the hill.

TIDES: Slack occurs one hour before and six hours after high water Dover. Visibility is usually best at high water slack.

HOW TO FIND IT: The charted position of the Kyarra is 50 34.90N, 001 56.57W (degrees, minutes and decimals).

There is usually a buoy tied to the railing amidships. Pulled under by the tide, it will surface at slack water. Other published co-ordinates agree with the latitude, but longitude can vary by as much as 0.03 minutes west.

This is more a sign of the size of the ship than a fundamental inaccuracy in the numbers.

DIVING AND AIR: Swanage Diver, skipper Peter Williams (01929 423551) or Sidewinder and Stella, skipper Martin Jones (01929 427064, Swanage Boat Charters Website). Air and nitrox are available on Swanage Pier from Divers Down (01929 423565).

LAUNCHING: Slips are available at Kimmeridge, Swanage and Poole.

ACCOMMODATION: There are many B&Bs, small hotels and campsites. Contact Swanage Tourist Information (01929 422885).

QUALIFICATIONS: Not for novices, but you can have a good dive without getting into decompression.

FURTHER INFORMATION: Admiralty Chart 2610, Bill of Portland to Anvil Point. Ordnance Survey Map 195, Bournemouth, Purbeck and Surrounding Area.

Dive Dorset, by John & Vicki Hinchcliffe. Shipwreck Index of the British Isles Vol 1, by Richard & Bridget Larn. Dorset Shipwrecks, by Steve Shovlar.

PROS: A large wreck, partly intact with plenty to see.

CONS: Can be very busy on the wreck, above it, and at Swanage Pier.