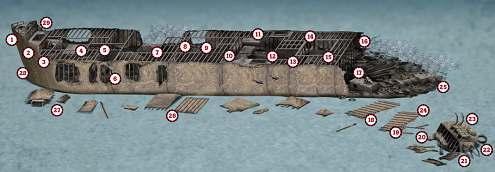

‘And about time!’ you cry. Why has it taken Diver so long to get round to one of Britain’s most popular wrecks? JOHN LIDDIARD explains our tortured thinking in a specially extended springtime Wreck Tour. Illustration by MAX ELLIS

READERS HAVE BEEN REQUESTING a Wreck Tour of the James Eagan Layne for years, and I have deliberately been putting it off. One reason was that Diver ran quite a detailed article about diving the wreck in May 1997 and I felt that it needed to wait its turn before I could cover it in this series of tours.

Anyway, seven years on I have dived it afresh to make sure that I am as up to date as possible with the tour and sketch. To compensate for the wait, I begged the boss for an extra page so that I could do the wreck justice.

A dive on the James Eagan Layne nearly always begins on the buoy tied to the bow (1), which, depending on the tide, rises to about 8m. It’s what makes the James Eagan Layne such a great wreck to dive. Beginning this shallow, anyone can do it.

Rather than continuing straight back inside the holds, I suggest dropping over the point of the bow and descending just a few metres, not all the way to the seabed but just far enough to be able to look back along both sides of the hull and the masses of anemones.

There is also the possibility of sighting one of the big shoals of fish that sometimes loiter in the current just off the bow.

Swimming along the port side, the first navigation checkpoint is the anchor hawse-pipe (2). Neither anchor nor chain are any longer there but it is full of anemones, and wrasse seem to have fun chasing each other up and down it.

Stay at about the same depth and cruise further back along the hull, which is soon broken down to the main deck, providing a route back inside (3) without having to ascend. It’s easy to swim the length of the main body of the wreck from hold to hold inside the wreck with no risk and a simple exit upwards, so that is how our tour will continue for now.

Liberty ships such as the James Eagan Layne were of a shelter-deck design, meaning that there was an additional deck built above and enclosing the main deck, providing additional sheltered space for cargo.

Crossing the ribs to the first cargo hatch (4), you are actually crossing the main deck, the shelter-deck having long since collapsed, eroded and been cleared by explosives at various stages of the wreck’s evolution.

Dropping into number 1 hold, the hatch and a fair amount of debris from the deck can be seen to have fallen in. At the forward end, the anchor-winch is sloped against the bulkhead. Ribs and hull from the starboard side have fallen in along most of the hold.

On the port side, fish swim in and out where hull-plating has decayed, leaving ragged holes blocked to any but the skinniest of divers by upright hull ribs.

Among the remnants of cargo are pickaxe heads, vehicle batteries and piles of things that I am at a complete loss to identify, as was everyone I asked.

At the back of the hold, the bulkhead is just a frame (5) with gaps big enough to swim through, some of the uprights having collapsed to make room for even the most heavily equipped diver.

Immediately on entering number 2 hold, you’ll see a pair of cargo-winches that have fallen upside-down beneath their mounting-plates on either side of the hold (6). The corresponding mast and deckhouse have also fallen into the hold, a little off-centre to the port side of the hold.

This is the most broken of the forward holds, the starboard side being almost completely open (7). There are some big steel bowls at the back of this hold, which are actually cauldrons for a field kitchen.

Access to number 3 hold is again through the broken skeleton of the separating bulkhead (8). The most interesting cargo here is a pile of spoked wheels just by a break in the starboard side (9).

These are the sort of wheels used for agricultural machinery and should not be confused with the railway wheels that the James Eagan Layne was also carrying. There are quite a few piles of similar wheels further aft.

Liberty ships were configured with three holds forward and two aft, so the next bulkhead (10) separates tnumber 3 hold from the engine-room.

The boilers were fired by oil, and the rectangular tanks can be found tight against either side of the hull (11). Between the tanks, the two Babcock water-tube boilers are rectangular in section and mounted across the ship. Between the boilers and the fuel-tanks on either side are steel canyons wide enough to swim through.

Back in 1997, when I last reported on the James Eagan Layne, the conventional triple-expansion steam engine (12) was largely obscured by debris from above. But now this has mostly collapsed further to leave the top of the engine nicely exposed. Off to the starboard side, a single-cylinder auxiliary engine looks as if it drives a pump.

Aft of the engine, the wreck is split along the centre-line by a pair of fuel-oil tanks, both accessible through the bulkhead at the rear of the engine-room or from above. Close to the bottom of the port-side compartment (13), an irregular hole towards the centre of the wreck provides access to the propeller-shaft tunnel.

For a properly equipped and experienced diver, the tunnel can be swum through all the way beneath number 4 hold but, be warned, it is a very tight squeeze in places.

For those not so inclined, the aft bulkhead from the port tank is a bit too intact for most divers to wriggle through. The way aft is back into the engine-room to the starboard fuel tank, where the bulkhead to number 4 hold has completely collapsed (14).

Number 4 hold (15) contains more of the neatly piled rows of steel beams and a scattering of the usual cargo. This is the last of the intact holds, with the bulkhead at the rear (16) leading to the pile of debris that used to be number 5. The torpedo hit the James Eagan Layne on the starboard side, just aft of this bulkhead.

At the centre-line of the hold and tight against the bulkhead, the propshaft tunnel can just be found emerging from the debris, the exit of the advanced swim-through I mentioned earlier.

Next comes part of the James Eagan Layne that many divers have trouble finding, the last bit of the stern, so I will go into detail on my method of getting there.

To the port side of number 5 hold lie the remains of the deckhouse and mast-foot that would have spanned the deck between numbers 4 and 5 holds (17).

Dropping over the broken side of the wreck as close to the bulkhead as possible, the first waypoint is a pair of spoked wheels from the cargo.

Just out and aft of these is a ribbed section of hull stretching further out from the wreck (18). Crossing this and a few metres of seabed, another section of hull is usually visible without having to swim out blindly (19). Right at the outer and aft end of this are some ribs pointing aft, partly buried in the seabed.

These point to the stern, which should either just be visible or at least show as a shadow in the distance.

Depth is about 26m depending on the tide. The first recognisable item of wreckage is the rudder (20), which lies across the route. To the right is forward, and to the left aft.

Turning forward along the starboard side, the hull soon comes to a clean break across a bulkhead. At the lower corner, it is possible to get inside and ascend. There used to be an air-pocket here, collected from diver’s bubbles, though I didn’t check that it still existed last time I dived the James Eagan Layne.

Fed by stale divers’ air at 20m, this is definitely not the sort of pocket from which you should ever risk breathing.

Back outside and continuing across the stern, the ribs of the bulkhead are a mass of plumose anemones. A few scraps of wreckage lead in a “forward” direction, including the spindle of a cargo-winch, though this is obviously not the way back to the main body of the wreck.

Rounding the next corner to the port side of the stern, the boat-derricks are broken slightly outward to almost touch the seabed (21). Then, right at the stern, a rounded and toothed ring on the seabed (22) is part of the traverse mechanism for the stern gun-mount, visible as a corresponding ring on the stern deck.

On the upper starboard edge of the stern deck, the shallowest point of the stern is marked by the boat-derricks at 16m (23).

So how did the stern get to be this far from the wreck? Some claim it is the result of clearing the wreck with explosives but I think otherwise. The James Eagan Layne sank by the stern, across a mild current. The propshaft had already been broken by the torpedo explosion.

The rudder and propeller would have dug in, dragging and causing the wreck to break forward of the rudder. The already damaged number 5 hold would then have broken up completely, the rest of the wreck settling more gently away from the broken-off part of the stern.

To get this far is a long dive, so this could be the point at which to surface on a delayed SMB, though make sure this is agreed with the boat-skipper beforehand, because he could be expecting divers to surface back at the bow.

For a marathon dive, there is still plenty of wreck to see. The main body lies roughly to the north-east, though I advise against using a compass. The reliable way to get back to it is to retrace the route out to the closest section of hull (24), then follow the inside edge of the debris back to the side of number 5 hold.

Cargo spread among the remains of the hold includes just about everything already encountered, with the addition of well-concreted bales of wire to the starboard side. Right at the tail-end of the debris is the last part of the propeller-shaft and tunnel and stern recess (25).

This is much easier to swim through than the earlier section below number 4 hold. It is also bent somewhere between 20 and 30° from the line of the wreck. To my mind this is further evidence of the stern digging in as it sank, causing the wreck to break as it has.

On the way back to the bow there is still plenty to see along either side of the wreck or along the deck. I prefer the port side along the seabed.

Various sections of hull and deck lead to a large section amidships that it is possible to swim below (26), then another boxed section just back from the bow (27) with a bent girder across it, through which it is also possible to swim.

We then come to why I like this route back to the bow – the chance to ascend along its edge (28), looking up past masses of anemones and, on the right day, shoals of fish.

Level with the hawse-pipes, duck back round and inside (29), out of the current and shallow enough for a slightly deeper than usual safety stop, hanging onto the railing. There is just so much to explore, and you can understand why this is such a long Wreck Tour, and why most divers take several dives to see even half of the James Eagan Layne.

THE MAKING OF YOUR FAVOURITE WRECK

The USA built 2,700 Liberty ships for World War Two. But in most diving logbooks there is only one – the James Eagan Layne, the most dived ship in British waters, writes Kendall McDonald.

She was one of 120 Liberty ships named after men of the American Merchant Marine killed by enemy action during the war. James Eagan Layne earned his Liberty ship when, as Second Engineer Layne, he was killed in the engine-room of the Esso Baton Rouge tanker, torpedoed off the east coast of the USA in 1942.

The keel of the Layne was laid down in October 1944, one of the 188 Liberty ships to be built by the Delta Shipbuilding Company of New Orleans.

Just 40 days later, on 2 December, widow Marjorie Layne cried out: “I name this ship James Eagan Layne, and may God bless all who sail in her!” as she swung the champagne bottle to shatter on her bow. Liberty Ship 157, bearing her late husband’s name, slid sideways into the Mississippi.

James Eagan Layne had needed 43 miles of welding to put her together. She was 7,176 tons gross, 132m long with a beam of 17m and had two oil-fired boilers. Her standard triple-expansion engines had been built at the Joshua Hendy Ironworks of Sunnyvale, California. Fitting her out after her launch took another 16 days.

At the beginning of March, 1945, her maiden voyage began. She steamed across the Atlantic, holds crammed with war supplies, lorries, jeeps, railway rolling-stock and tank parts, to Barry Roads, where she was joined to Convoy BTC 103 for the rest of her voyage to Ghent. But, like 50 other Liberty ships, her maiden voyage was to be her last.

Kapitanleutnant Ernst Cordes in U1195 found the James Eagan Layne in a break in the fog on 21 March, as she was passing close to South Devon’s West Rutts.

She was the lead ship in the second column of the convoy and, shortly before 4pm, Cordes sent a single torpedo into her. It struck just aft of her engine-room and she lost all power immediately, swishing to a halt on the calm sea. She was badly holed in two of her rear holds and water was rising fast.

She sat there, with nobody making any noise for fear of attracting a second torpedo, until two Admiralty tugs arrived and took off her crew of 42 and the 27 gunners who manned her six AA-gun emplacements. Then they took her in tow.

They aimed to beach her, but the inrush of water was too great and the tugs had to cast off as she sank to the sandy bottom a mile from Rame Head at 10.30pm. Some salvage started at once. Her guns were taken out and any easy-to-reach army equipment was lifted out of her holds.

The war ended soon after, and no more work was done until some minor salvage by an Icelandic firm in 1953. In 1967, a British firm salved the prop, condenser and propshaft. More recently, 60 brass shellcases were salved from under a 5.5in gun that had been mounted on the stern.

Amateur divers first visited the James Eagan Layne in 1954, when it was possible to tie up to one of the masts that still showed. They haven’t stopped diving this particular wreck since.

TOUR GUIDE

GETTING THERE: Follow the A38 into Plymouth, then, before entering the city-centre, cross the river Plym on the A379 towards Kingsbridge. Mountbatten is signposted to the right and is almost three miles on, following the signs through the back roads.

DIVING & AIR: Deep Blue Diving

ACCOMMODATION: Rooms are available at Mountbatten.

TIDES: The James Eagan Layne can be dived at any state of the tide.

HOW TO FIND IT: The GPS co-ordinates are 50 19.609N, 04 14.720W (degrees, minutes and decimals). The wreck lies with its bow to the north, about 100m north-east of the buoy.

LAUNCHING : There are large slips at Mountbatten and Queen Anne’s Battery in Plymouth.

QUALIFICATIONS: The shallower parts of the wreck can be dived by beginners.

FURTHER INFORMATION: Admiralty Chart 1613, Eddystone Rocks To Berry Head. Ordnance Survey Map 202, Torbay And South Dartmoor Area. Dive South Cornwall, by Richard Larn. The Wrecker’s Guide to South Devon Pt 1, by Peter Mitchell.

PROS: Something for everyone, from beginners to wreck-wrigglers who like long and narrow holes.

CONS: Can get busy, especially on a bank holiday weekend.

Thanks to Richie Stevenson.

Appeared in Diver, April 2004

I sugg

Est you up date your wreck tours. The bow of the JEL is lying on the sea bed