This 1930s motor yacht hit the news in 2004 when its true identity was revealed. JOHN LIDDIARD travels to Northern Ireland to dive this rich man’s toy. Illustration by MAX ELLIS

BACK WHEN THE WRECK TOUR SERIES STARTED in 1999, I received an invitation from Lisburn Sub-Aqua Club to dive the wreck of the Alisdair, a classic 1930s motor yacht sunk in 21m in Ringhaddy Sound, at the back of Strangford Lough.

I had dived the wreck in the past and thought it was a good candidate, though with one thing and another I didn’t get round to diving it until May 2004, during a trip to Northern Ireland hosted by DV Diving.

Anyway, the delay was fortuitous because I would have been writing about the wrong wreck. Queens University SAC had recently discovered that it was in fact the Alastor, a slightly larger yacht originally built for the aircraft designer Sir Thomas Sopwith in 1929.

So this month’s Wreck Tour is now the correctly identified Alastor, a motor yacht requisitioned by the Admiralty in World War Two, and which caught fire and sank at its mooring in March 1946.

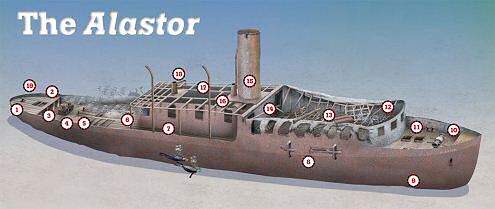

The Alastor can be dived either from a boat or as a long shore dive. For a boat dive, a marker buoy is attached to a small bollard at the stern at 18m (1), while for a shore dive a line from the quay leads into the port side of the stern (2).

Between the two, an open hatch (3) leads down to a small silt-filled compartment below the deck.

Forward along the centre-line of the wreck, a pair of capstans stand on a pedestal clear of the deck (4), with a pair of small bollards nearby (5).

Most of the rear deck is just a framework of steel deck-beams, with the teak decking rotted away. The small hold area below the beams would have been accessed through a larger hatch (6) although, like the stern locker, it is silted almost to the level of the deck-beams.

Continuing forward along the starboard side of the wreck, a covered walkway (7) leads alongside the superstructure, with a pair of boat derricks rising above the wreck and swung out in the position in which they would have been for lowering or recovering the boat.

Staying at the level of the main deck, the walkway ends and the forward part of the superstructure spans the width of the hull. The sides have folded in slightly along the middle of the line of rectangular window frames.

Below the window frames, a pair of crossed retainers (8) would have held doughnut-shaped lifebuoys to the outside of the hull, more as decoration than for ready deployment.

While the stern is buried low to the silt, the bow of the Alastor (9) is further into the current of the channel, and is surrounded by a considerable scour to 21m, the only part of the wreck not accessible to those with basic open water qualifications. The hull’s covering of tunicates slowly gives way to patches of dead man’s fingers and anemones at the tip of the bow.

Back at main deck level, the bow deck is intact and recessed with an anchor-winch (10) and a pair of small bollards to either side. This is followed by two small hatches (11) to the bow locker and forward hold. Like the aft hold, these are filled almost to deck level with silt.

The forward part of the superstructure would once have been luxurious accommodation. Now, the upper deck has rotted and the supporting beams have collapsed inside. A pair of steel frames (12) would once have been panelled with wood, as would the sides of the wheelhouse. A little further aft, a mast lies across the deck (13).

Any wooden partitions between the cabins are long rotted to dust, though the bath and tiled floor of the bathroom (14), located to the starboard side where the superstructure narrows, gives evidence of individual cabins.

An unusual sight for any wreck is the funnel still standing (15). In the Alastor’s case, the funnel is a purely decorative cover for the exhaust from the diesel engine below, not the essential flue needed for efficient burning in the boilers on a steam-powered ship.

To the starboard side of the funnel, looking down between the deck beams, you’ll see an upright cylinder (16). This is the water tank, separated from the bathroom by an intact steel bulkhead.

Behind the funnel, a large opening along the centre-line of the yacht (17) would have provided ventilation for the engine-room below although, as with the other hatches, the way down is silted and the engine itself is covered.

As on the starboard side, the port side was fitted with a pair of boat derricks, but the aft derrick has collapsed across the beams of the upper deck (18).

As a boat-dive, a brief first pass round the wreck will have taken 15 minutes or so, leaving plenty of time to go round again more slowly before ascending the buoy-line. As a shore-dive, one pass round is probably enough before following the line back to the shore. In either case, the departure point is back at the stern (19).

BUILT FOR A SPEED DEMON

Most divers thought it was called the Alisdair. When that proved wrong, they thought it was the Allister. They were nearly right. But it took the divers of Queen’s University Sub-Aqua Club, Belfast, to find out the true name and history of this 44m steel motor yacht of 340 tons. It was in fact built for Sir Thomas Sopwith, writes Kendall McDonald.

Thomas Octave Murdoch (‘TOM’) Sopwith, born in 1888, was one of the first Englishmen to learn to fly. Four days after getting his licence in 1910, he had set a duration record of 108 miles in three hours, 12 minutes. Height, speed and distance records followed. He then started building aircraft to his own designs. His Sopwith Camel biplanes were said to be the greatest fighters of World War One.

After the war, he found time to break the world water speed record for motor boats, become a famous racing-car driver and join Harry Hawker in developing military aircraft. As head of the Hawker Siddeley Group, Sopwith played an important role in developing the monoplane that would become the famous Hurricane of the Battle of Britain. The group was responsible for the first British jet fighter, the Meteor, in addition to the Hunter, Javelin, Sea Hawk and the huge Vulcan bomber. Sopwith died in January 1989, aged 101.

In 1927, yacht-builders Camper & Nicholson had launched the Vita, a luxury motor yacht, largely designed by Tommy Sopwith. To suit this man of speed it was meant to be fast, but was perhaps not fast enough for him, because within two years he had sold it to Sir John Shelley-Rolls. He renamed it Alastor, after a poem by his ancestor, Percy Bysshe Shelley.

Was it wise to use the name? Evil spirits were called “alastors” by the ancients. But Sir John seems to have been pleased with his Alastor, for he still owned her in 1939, when the Ministry of War Transport acquired it for use as a stores ferry, carrying supplies out to naval vessels at the entrance to Strangford Loch for refuelling and reprovisioning.

It carried out this service throughout the war, but on 11 March, 1946, it was decided that the shabby vessel needed repainting before being handed back to its owner. It was moored some 80m off Ringhaddy Quay for its crew to start work.

Whether the fire that broke out in the galley was the result of a pre-paint brew-up, no one appears to know, but it destroyed the interior and the Alastor sank five days later. All six crew escaped unhurt.

TOUR GUIDE

GETTING THERE: Norse Merchant Ferries’ Liverpool (Birkenhead) to Belfast service, 0870 600 4321. From Belfast, take the A20 to Portaferry, or the A22 and local roads to Ringhaddy

TIDES: Slack water is not required, but visibility is generally better on a flood tide.

HOW TO FIND IT: The Alastor lies pointing roughly east, at GPS position 54 27.06N 05 37.71W (degrees, minutes and decimals). For a shore dive, a line leads from the ladder on Ringhaddy Quay to the stern of the Alastor, which is 80-100m from shore.

DIVING, AIR & ACCOMMODATION : DV Diving, 02891 861686 / 464671.

LAUNCHING : RIBs can be launched at the ferry jetty in Portaferry, though care must be taken not to obstruct the ferry.

QUALIFICATIONS: The Alastor is shallow enough for anyone to enjoy.

FURTHER INFORMATION: Admiralty Chart 2156, Strangford Lough. Irish Wrecks Online by Randall Armstong.

PROS: Well-sheltered in bad weather. Slack water is not required.

CONS: It can be confusing trying to pick out the right buoy among all the yacht moorings.

Thanks to David and Tony Vincent and Steve Phillips.

Some other Northern Ireland Wreck Tours: Bangor, Castle Eden, Hunsdon, Neotsfield, William Mannell