This cargo vessel, torpedoed by UB40 off east Devon during WW1, lies in 32m and offers plenty of ‘engineering’ for divers to enjoy, reports JOHN LIDDIARD. Illustration by MAX ELLIS

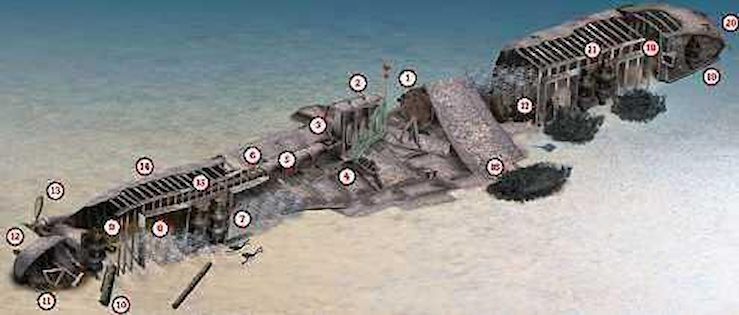

FROM THE POINT OF VIEW OF AN ECHO-SOUNDER, the wreck of the Gefion is split into three distinct sections – the bow and forward holds; the stern and aft holds; and, between these, the boiler and engine.

Any of these would make good targets onto which to drop a shot, so this month’s tour begins on the Gefion’s boiler (1), partly covered by a hull-plate resting against it.

If you imagine yourself lying along the top of the boiler with the hull-plate sloping off to your left, you will be facing aft towards the engine which, depending on the conditions, might or might not be visible from here.

Heading aft from the boiler, the engine (2) is a typical triple-expansion unit, with the smaller high-pressure cylinder towards the boiler and the larger low-pressure cylinder at the aft end.

A section of trawl-net is caught against the starboard side of the engine and held aloft by a float, so be careful as you approach it.

Immediately behind this are the remains of the box enclosing the thrust-bearing (3), firmly anchored against the keel to transfer the forward thrust from the propeller to the hull of the ship.

The inner part of the thrust-bearing on the shaft is exposed where the non-ferrous metal of the bearing plates has been salvaged. A little to starboard, sections of grating from the engine-room decking are scattered among the wreckage (4).

The propeller-shaft tunnel continues to provide a line aft, initially intact (5), then broken open to expose a section of shaft before the shaft also breaks (6). From here, the complete aft section of the Gefion from the number 3 hold to the stern is reasonably intact, but fallen to starboard (7).

Many of the plates from the upper port side of the hull have decayed to leave a lattice of ribs, covered in anemones and dead man’s fingers. From the broken coaming of number 3 hold, this provides plenty of light to continue aft through the inside of the hold, popping out again through the hatch of number 4 (8).

A section of mast rests on the seabed below, then more mast just aft of the hold with the stern winch (10). Just above and between the two is a heavy steel hook, the sort that on a tug would have been used to hold the tow cable (9). Perhaps the Gefion was rigged for towing a barge?

The final part of the stern has cracked loose from the hull, but only enough to settle the starboard side against the seabed. The steering quadrant is rotated slightly to starboard (11), then, rounding the end of the stern, the rudder-shaft disappears into the silt at 34m (12).

Further towards the keel, the propeller also disappears into the silt, with just one blade standing upright and the edge of a second blade showing (13).

Having seen the stern, our route now heads forward again, rising over the port side of the hull across the open and decorated ribs that we earlier swam beneath (14). Crossing to the deck, a pair of winches (15) fills the space between the two hold-coamings.

Staying on the starboard or deck side of the wreckage and continuing forward should lead to the hull-plate that has fallen across the boiler (16).

If in any doubt about the route, the propeller-shaft, engine and then the boiler provide easy way-points to navigate back amidships.

The seabed off this area of the wreck is littered with coal from Gefion’s cargo, then more coal leads into the back of the second hold (17).

Like the stern, the forward part of the Gefion rests on its starboard side, hull-plates missing from the upper port side to provide plenty of light inside.

This leads to an interesting question: did the Gefion originally sink upright, then break forward and aft of the engine, with both the bow and stern falling to starboard? Or did it sink on the starboard side, so that when it broke the central section rolled to port and upright again?

For most wrecks, the sinking upright answer is obvious. For the Gefion, I am not confident enough to put my money on either solution.

As with the stern part, it’s an easy and well-lit swim through the forward holds to where the bow has split from the hold (18), then out to the bow deck (19).

On the bow deck, a small aft-facing cuddy covers a hatch down to the forepeak, then a relatively small anchor-winch is still attached to the solid steel deck-plates.

Chains lead tight into the hawse-pipes, with the port anchor held in close on the upper side of the bow (20) and the starboard anchor held in tight below.

Making use of a dive-computer, following the upper side of the bow back takes our route shallower to where the forward cargo winches can be seen between the forward holds (21), the highest part of the bow section and a convenient point to release a delayed SMB to surface.

UB-40’S 50TH VICTIM

OBERLEUTNANT HEINRICH HOWALDT of the Flanders Flotilla ranked high on the German list of U-boat aces. He and UB-40 had sunk 49 Allied ships, totalling more than 80,000 tons.

However, he was having trouble bagging his 50th victim in the breaking swells and howling winds of the afternoon of 25 October, 1917, writes Kendall McDonald.

Howaldt’s target, the 1123-ton, 69m Admiralty collier Gefion, had been built in Bergen, Norway, just before the start of World War One, so was designed to cope with the kind of huge seas she was now meeting, 10 miles north-east of Berry Head, Devon.

Despite the seas and the 1,600-ton weight of her cargo of Welsh coal, which she was carrying from Penarth to Honfleur, the Gefion was making a steady 10 knots. Her speed caused the commander of the storm-tossed UB-40 some problems in loosing a torpedo at her from one of his bow tubes. However, at 3.30 Howaldt fired from periscope depth.

James Minto, the master of the Gefion, was below. The chief mate had the watch and was on the bridge. He spotted the wake of the torpedo coming at an angle of 20° to the beam on the port side. He put the helm hard to port and the Gefion began to respond, but it was a little too late. The torpedo, running deep, smashed into number 2 hold some 2.5m below the waterline, and the explosion opened up a huge hole in her side.

The collier began to sink rapidly. Her crew made for the boats, switching to the starboard one when they found that the port boat had been smashed. Nine men scrambled in and pulled away from the sinking ship, but the other 16 were left struggling in the water as their ship sank beneath them.

The men in the starboard boat managed to row back and drag five more men aboard, but the master and a donkeyman were never found. The survivors were picked up some hours later by a fishing smack and landed at Brixham. Not one of them claimed to have seen the submarine that sank them.

Howaldt got UB-40 safely back to base at Bruges, but when the Germans were forced to evacuate Flanders in October 1918, she was one of four damaged U-boats blown to pieces by men of the Flanders Flotilla to avoid them falling into Allied hands.

The wreck of the Gefion belongs to Exedive BSAC.

TOUR GUIDE

GETTING THERE: From the M5 or A38 turn left on the A376 for Exmouth, the A380 and A381 for Teignmouth, or the A380 and A3022 for Paignton.

TIDES: Slack is two hours before high water or low water Exmouth.

HOW TO FIND IT: The GPS co-ordinates are 50 30.080N, 3 15.228W (degrees, minutes and decimals). The bow points west.

DIVING, AIR : Wave Chieftain II, 01626 890418, Visit Deepsea, 01384 402210, Teign Diving Centre, 01626 773965.

LAUNCHING : The most convenient slipway is at Teignmouth.

ACCOMMODATION : B&B 01395 264193. Dolphin Hotel 01395 263832.

QUALIFICATIONS: Well-suited to those qualified for the depth but not for decompression diving, such as PADI Advanced or newly qualified BSAC Sport Divers.

FURTHER INFORMATION: Admiralty Chart 3315, Berry Head to Bill of Portland. Ordnance Survey Map 192, Exeter & Sidmouth. World War One Channel Wrecks, by Neil Maw. Dive South Devon, by Kendall McDonald. Shipwreck Guide to Dorset and Lyme Bay, by Nigel Clarke.

PROS: Plenty of engineering and some bright and colourful swim-throughs.

CONS: Be careful about the net at the front of the engine.

Thanks to Richard Tibbs.

Appeared in DIVER January 2006