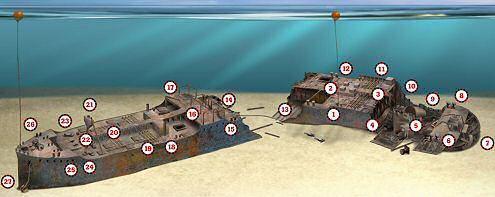

This armed tanker sunk in WW2 in the Moray Firth makes for a great club outing, says JOHN LIDDIARD. Illustration by MAX ELLIS

A BIG WRECK AND CONVENIENTLY SPLIT IN HALF, the San Tiburcio is often explored as two separate dives – a first dive on the slightly deeper stern part, and a second on the shallower forward part.

Well, you could dive it like that.

There are buoys attached to each part. But there is also a line conveniently tied between the two, placed to assist those who want to dive it all in one go. Like me.

So our long tour of the San Tiburcio begins on the northernmost of the two buoys, descending to the port side of the wreck just aft of the break (1), the depth to the deck being a little short of 30m.

At the side of the deck is a pair of small bollards, then inwards the centre line of the deck pump house (2) forms a small island in the walkway that used to stand above the deck from bow to stern.

Forward of the island the walkway is missing, but aft it stretches back to the point at which the stern has been blasted and broken (3).

In 1989 a team of Navy divers used explosives to blow the stern open to recover ammunition from the gun. Perhaps they overdid the amount of explosive, or perhaps the explosion just weakened the structure of the ship sufficiently for nature and gravity to do the rest. Either way, the entire engine-room area of the San Tiburcio is devastated.

The 4in gun rests partly obscured among debris on the port side (4), with the tipped-over gun-mount just aft (5).

Aft again, and a pair of large bollards (6) marks the start of the curved part of the stern. The stronger structure of the stern has retained some integrity to the deck and hull. Even so, its link to the rest of the ship has been weakened to the point of it having fallen to port, the deck touching the silty seabed at 35m.

The collapse has pushed the rudder-post and steering-quadrant out of position (7). Following the curve of the stern, the upper (starboard) side rises 3 or 4m above the seabed, before breaking down again at the engine-room bulkhead (8).

The Navy team didn‘t do that thorough a job of clearing out the shells, because several can be found resting on a level deck-plate aft of the engine-room, a small display created by divers (9).

At the forward end of the engine-room (10), the San Tiburcio‘s boilers are just visible among the debris if a dive-light is poked through the right hole.

Our route now moves back above the main deck (11), crowded with pipework and hatches to the oil tanks. Along the starboard side, the deck continues forward past a pair of small bollards corresponding to where the buoy is attached on the port side, then on to a much larger pair of bollards (12).

This is the point at which to cross back to port and ascend the buoy-line, if doing the wreck in two dives.

To continue to the bow section, the break along the port side of the hull should be followed almost to the seabed, where a line leads off into the blackness (13). The line ascends slightly and, some 20m or so away, the other end is tied in to the forward part of the wreck, just below main deck level and to port of the centre-line (14).

The San Tiburcio broke in two aft of the amidships superstructure. The deck of the wheelhouse bridges the main deck at the same height as the walkway, leaving a nice swim-through along the main deck below (15). For those splitting the San Tiburcio into two dives, it is easy enough to descend the buoy at the bow and follow the raised walkway all the way back to rejoin our tour.

The upper part of the superstructure has decayed to no more than a frame. To the port side, a pair of derricks overhangs where a boat was launched (16). The corresponding derricks on the starboard side have fallen to rest on the deck (17).

The essential tanker engineering is more evident and intact forward of the superstructure.

Below deck, the hull is sub-divided into a grid of tanks, their locations marked by a corresponding grid of hatches on the deck. Some of these are still covered, while others are open, although there is little point in venturing inside the open tanks.

Passing the first set of hatches, the central walkway crosses a small pump-house (18), then the network of pipes and valves that covers the deck comes together with an array of cross-pipes for cargo-loading and discharge (19).

With the hull sub-divided into many self-contained tanks, the design of a tanker could get away with a much lower freeboard than a dry cargo ship, leaving the main deck close to the water and often awash in a heavy sea.

So the tanker’s stilted walkway runs from bow to stern, providing a safe means for crew to walk between the forecastle, the wheelhouse and the engines at the stern. The walkway (20) is intact all the way forward.

The forward mast (21) rises to the side of the walkway, broken a few metres further up. With a beam of more than 16m, it is hard to tell which is off-centre to make room for the other. Below the walkway, a small cargo-winch assists the mast in serving a dry hold (22).

The walkway ends in steps down to the main deck behind the hold. Tucked underneath are a pair of spare anchors.

On the deck to the starboard side, an elongated teardrop shape with a finned tail is a mine-sweeping drone or “fish“ (23). The finned tail is broken off and rests just out and aft of the main body of the drone. A second similarly broken fish can be found on the port side of the deck (24).

The fish would have been deployed on long cables from the bow, trailing off to either side of the ship.

Any mine encountered that did not actually hit the bow would slide to the end of the cables and detonate against the expendable fish.

If deployed, they might well have saved the San Tiburcio from the mine that it struck amidships. But the tanker was travelling a swept and supposedly safe channel. Mines were not expected, so the minesweeping fish were not deployed. On 4 May, 1940, the San Tiburcio struck a mine amidships and broke in two.

Travelling round the edge of the bow, a line of empty portholes is nearly obscured by dead men’s fingers (25). On deck, pairs of large bollards frame the anchor-winch (26).

At the bow, the port anchor and chain has spilled out and rests on the seabed (27). The starboard anchor remains tight into its hawse-pipe.

Finally, the buoyline is attached right at the bow. With no current to consider, it is easy to follow the line up and wait out any decompression.

HALVED BUT SLOW TO DIE

The German mine exploded, splitting the tanker in two as though she had been cleft by

a giant axe from port side to starboard rail. Surprisingly, though tons of sea water rushed into this 16m slash, breaking her back, the two halves of the 126m San Tiburcio stayed afloat for more than half an hour, writes Kendall McDonald.

Captain William Fynn took advantage of this buoyancy provided by her sealed tanks, which had held 2,193 tons of fuel oil when she set out from Scapa Flow for Invergordon in the Cromarty Firth, and got all his crew, uninjured, into the boats.

They waited and finally saw the San Tiburcio sink. The sections sank upright, but followed one another in moments. The bow section is estimated by Rod Macdonald, the Scottish wreck-diver who visited her long before the boom in “San Tib” diving in the 1970s, as about 49m long and lying north-south, bow to the south. The 78m stern section is about 30m away and at right angles to the bow.

The San Tiburcio sank on the morning of 4 May, 1940, but the mine, one of eight, had waited nearly three months for a victim since being laid by U9, commanded by the man ultimately placed second in the list of German WW2 submarine aces. Korvettenkapitan Wolfgang Luth sank 43 Allied ships totalling 225,713 tons, outdone only by Otto Kretschmer, who sank 44 ships of 266,629 tons.

The San Tiburcio was built in 1921 by the Standard Shipbuilding Corporation of New York for the Eagle Oil and Shipping Co, and was registered in London on 12 March, 1921.

The Eagle Fleet had been created in 1912 by the first Viscount Cowdray. Its tankers carried Mexican oil through years of boom and slump.

At the outbreak of war the San Tiburcio was requisitioned by the Ministry of War Transport and fitted with a large stern gun. She was the first Eagle Fleet war casualty, but 16 of its tankers were lost by enemy action in WW2, and seven more badly damaged.

TOUR GUIDE

TIDES: There is little current at any state of the tide.

HOW TO FIND IT: The San Tiburcio lies pointing roughly south, GPS position 57 46.553N, 00 345.616W (degrees, minutes and decimals). The wreck shows up as massive on an echo-sounder.

DIVING & AIR: Moray Diving, Top Cat, skipper Bill Ruck, 01309 690421, 07775 802963.

ACCOMMODATION: Check with Aberdeen and Grampian Tourist Board, Elgin office, 01343 542666.

QUALIFICATIONS: Suitable for Advanced Open Water/Sports Diver.

LAUNCHING: RIBs can be launched in the harbour at Lossiemouth.

FURTHER INFORMATION: Admiralty Chart 115, Moray Firth. Admiralty Chart 222, Buckie to Fraserburgh. Admiralty Chart 223, Dunrobin Point to Buckie. Ordnance Survey Map 28, Elgin and Dufftown. Dive Scotland’s Greatest Wrecks by Rod Macdonald.

PROS: An excellent club dive with something for most levels of experience.

CONS: Surface conditions can be foggy.

Thanks to Bill Ruck, John Leigh and Tim Walsh.

Appeared in DIVER December 2006