Lying in the shadow of its big-name neighbours off south Cornwall, this coal-carrying steamer, a U-boat victim from World War One, is too often neglected by divers, says JOHN LIDDIARD. Illustration by MAX ELLIS

WITH THE JAMES EAGAN LAYNE AND SCYLLA NEARBY, larger, more intact, shallower and closer to Plymouth, it is hardly surprising that the 2,788-ton Rosehill is often overlooked by divers.

Also read: Meet Marie: Plymouth’s new wreck-diving attraction

I admit that, given a choice, nine times out of 10 I would opt for one of the Rosehill’s neighbours. But when I have visited the wreck in the past it has been a good dive, and it’s well worth the occasional look.

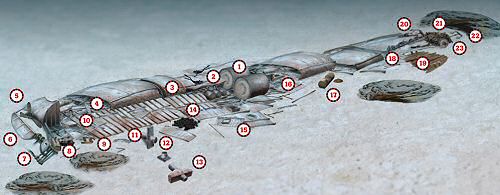

With the wreck almost levelled and surrounded by reef at around 30m, the only parts that show well on an echo-sounder are the boilers and the stern, with the boilers giving the most obvious echo. So that is where our tour begins (1).

Both boilers have rolled a little to starboard. Behind them, the triple-expansion steam-engine has also collapsed to starboard (2). Plates from the port side of the hull have fallen inwards, held up just enough to leave the crankshaft visible below.

In fact, the general pattern of collapse along the wreck is to starboard. Hardly surprising, because the wreck lies with bow to the north and the port side exposed to the groundswell from the west.

The propeller-shaft is partially obscured beneath the fallen hull, visible in places by peering beneath the collapsed plates (3), then breaking where the stern has fallen over.

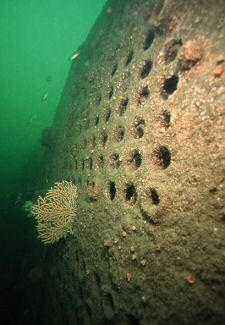

The hull-plates are home to a sparse forest of gorgonian fans, oriented across the ship to spread their branches to the gentle current that flows roughly parallel to the shore.

Continuing aft on the line of the propeller-shaft, then slightly to port, the tail-section of the shaft (4) disappears inside an intact section of keel at the stern. At the back of this section, the four-bladed iron propeller remains on the shaft, intact and with one blade pointing straight up to the surface (5).

Behind the propeller, the Rosehill’s rudder (6) lies flat to the seabed at about 30m, depending on the state of the tide. The bottom of the rudder-shaft remains attached to the keel, while further up the rudder-shaft is pushed away from the wreck where the steering quadrant is wedged against the seabed.

At the top of the rudder-shaft, the steering quadrant is quite small, the steering being assisted by a steam-powered steering-engine (7).

Between the rudder-post and the stern, the Rosehill’s 12-pounder gun and gun-mount lie on one side (8), with the breech of the gun in the sand and the barrel angled slightly up and towards the keel.

The deck from the stern is completely broken, with just pairs of bollards and curved sections of hull a reminder of the edges of the stern (9). In years past, cases of ammunition have been found in the area of the stern that would have been beneath the gun (10).

As the wreck has collapsed to starboard, our return forward is along the starboard (east) side of the wreckage. The Rosehill was a conventional four-hold freighter with two holds forward and two holds aft, masts and winch-gear between holds. So it is little surprise that, halfway back to the boilers, a section of mast rests just off the side of the wreck (11), held clear of the seabed by a cross-piece.

Following the line of the mast further out, just forward of the line are the broken remains of a winch (12). Scraps of mast continue further out, ending with another cross-piece (13).

Operating from Cardiff to deliver cargoes of Welsh coal, the Rosehill would have depended on shore facilities for loading and unloading, so winch-gear for operating the derricks would have been minimal.

Back on the wreck and continuing forwards, some of the coal cargo is spread across the seabed, level with the number 3 hold (14).

Further forward again and level with the Rosehill’s engine, small hatch-coamings (15) indicate the hatches from the ship’s bunkers. The space for storing coal for a marine boiler is always separate from the cargo. After all, while primarily used to carry coal, a ship could be loaded with other cargo.

Even when carrying coal, it might have been a different type to that best suited to marine boilers. Nevertheless, I doubt that would have been the case on the Rosehill’s final voyage. The coal was destined for Devonport and, presumably, the boilers of the Royal Navy.

Forward of the boilers, there is considerably less wreckage. Along the line between the two boilers and just a few metres forward, another steering-engine marks the wheelhouse end of the steering system (16).

A little further forward and off to starboard, the donkey-boiler (17) has rolled out from its original location in the stoke-hold. A domed cap has broken off and rests on the seabed behind it.

The largest part of the original bow structure is made up of some hull ribs shaped for the port side of the bow. These just rise from the seabed (18).

A little out from them, the bow deck (19) is a patch of wooden deck-planking partly obscured by sand. If the wooden decking is obscured, the edges are marked by two pairs of bollards. Some wafting of hands and fins should clear a light covering of sand away.

The other fittings for the bow have all broken loose. The port anchor is still in its hawse-pipe (20), broken from the hull. The chain from this leads to a big pile just forward of the anchor (21), with the starboard anchor stretched out forward (22).

The anchor-winch rests on the sand, next to the pile of chain (23). It’s a convenient place to pop a delayed SMB and surface.

TOUR GUIDE

GETTING THERE: Follow the A38 into Plymouth, then before entering the city centre cross the river Plym on the A379 towards Kingsbridge. Mountbatten is signposted to the right and is just under 3 miles on, following the signs through the back roads.

TIDES: The Rosehill can be dived at any state of the tide.

HOW TO FIND IT: The GPS co-ordinates are 050 19.793N, 004 18.520W (degrees, minutes and decimals). The wreck lies with its bow to the north, the boilers and stern being the highest parts.

DIVING & AIR: Deep Blue Diving, 01752 491490.

ACCOMMODATION: Rooms are available at Mountbatten

QUALIFICATIONS: The depth touches 30m, so requires PADI Advanced, BSAC Sports Diver or above.

LAUNCHING: There are large slipways at Mountbatten and Queen Anne’s Battery in Plymouth.

FURTHER INFORMATION: Admiralty Chart 1267, Falmouth to Plymouth. Ordnance Survey Map 202, Torbay & South Dartmoor area. Dive South Cornwall, by Richard Larn. The Wrecker’s Guide to South Devon Pt 2, by Peter Mitchel.

PROS: With the popular James Eagan Layne and Scylla nearby, the Rosehill is hardly dived.

CONS: Fairly flat and next to a reef, it can be difficult to locate.

ANOTHER VICTIM OF UB40

AT FIVE PAST SIX IN THE EVENING OF 23 SEPTEMBER, 1917, Captain Phillip Jones of the steamer Rosehill was in the chartroom, studying his ship’s position.

The Rosehill, built in 1911 as the Minster, was making good time on her voyage from Cardiff to Devonport, carrying 3,980 tons of Welsh coal. Captain Jones was therefore about to make a slight change of course earlier than expected, but at periscope depth away to port the German submarine UB40 was about to render that alteration unnecessary.

The first thing Captain Jones knew about that was when he heard the Mate shout from the bridge: “Torpedo coming!” By the time the captain reached the bridge, the Mate had put the helm hard over and had rung the engine-room for full astern. Rosehill started to swing, but too slowly.

Captain Jones saw the torpedo clearly enough to distinguish its red-painted nose. All the torpedoes UB40 fired on its many Channel missions bore the same red paint. This one smashed into the 95m Rosehill just behind the engine-room in No 3 hold.

The explosion sent the Rosehill’s stern 3m under. Believing that she would be gone in seconds, the captain ordered to the boats the 24 crew and the two Army gunners who manned the old Japanese 12-pounder on the stern. But despite the weight of coal in her holds, the steamer remained afloat.

An hour later, Captain Jones led a volunteer crew back aboard to see if they could save their ship. The Mate, Second Mate, Chief Engineer, four seamen and two firemen were with him.

Two privately owned tugboats soon arrived and started to tow Rosehill towards Fowey. Then two Admiralty tugs arrived and changed the direction of the tow to Plymouth, but she didn’t make it.

By 1.50am the Rosehill was showing signs of foundering. Everyone got off just in time as she broke in two and went down in Whitsand Bay in deep water. Her grave was marked by buoys from the patrol vessels.

That wasn’t quite the end. The Admiralty complained about the use of private tugs and their decision to tow Rosehill at first to Fowey.

Had she been towed from the first to Plymouth, it claimed, she would probably have been saved. The charges that had to be paid to the private tugs had, of course, nothing to do with it.

Thanks to Rich Stevenson.

Appeared in DIVER February 2007