Artificial intelligence has been used by the the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) to reveal 119 new ocean biodiversity hotspots in the western Indian Ocean – and it reports that the locations have only a “low overlap” with existing Marine Protected Areas (MPAs).

WCS, based at New York’s Bronx Zoo, has a mission to save wildlife and wild places worldwide and applies its Global Conservation Programme in all the world’s oceans and nearly 60 countries.

The organisation came up with a new AI model to enable scientists to map areas with especially high concentrations of fish and coral species. It says that because few of these hotspots are currently protected or conserved, the findings offer an important opportunity for new MPAs to be rolled out by the 11 nations concerned.

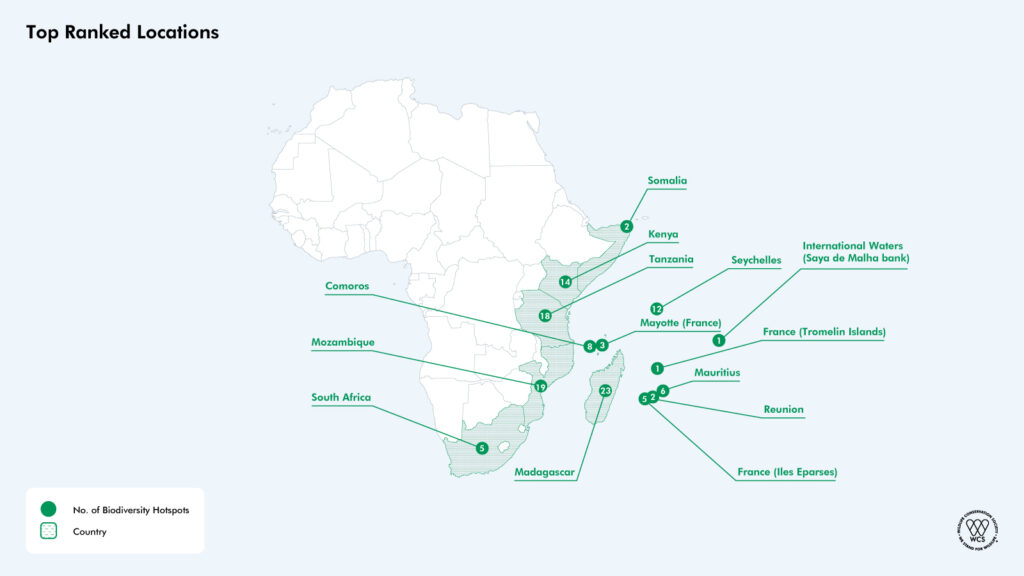

These are Comoros, Kenya, Madagascar, Mauritius, Mayotte, Mozambique, Reunion, Seychelles, Somalia, South Africa and Tanzania, with other sites identified in international waters.

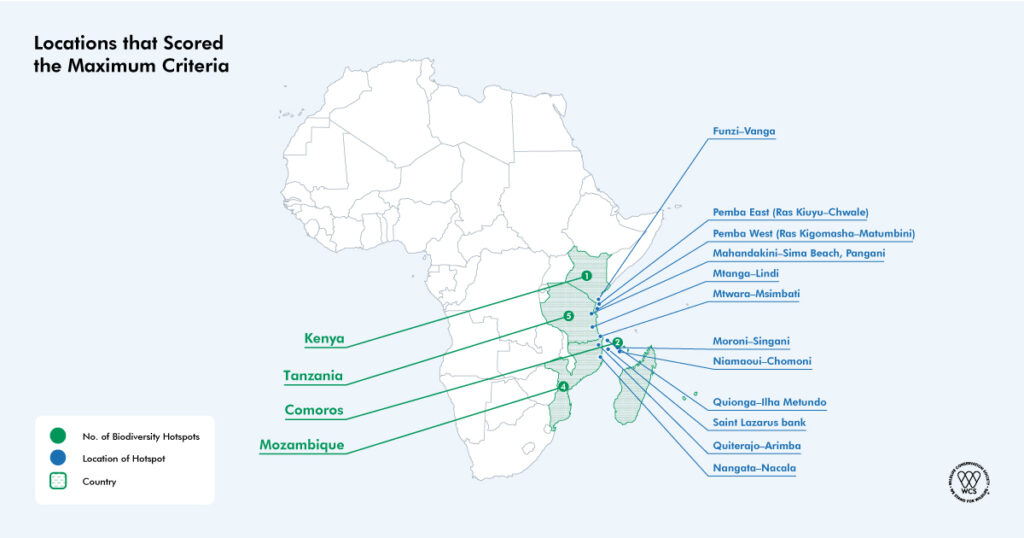

The largest national concentrations of hotspots were off Madagascar (23), Mozambique (19) and Tanzania (18), and the countries with the highest-scoring individual hotspots were Tanzania, Mozambique, Comoros and Kenya.

Faster and more accurate

“Various predictive models have been created for the past 10 or 15 years, but they were not very accurate at making empirical predictions,” explained WCS marine science director Dr Tim McClanahan. “Now, thanks to increasing computing speeds and more and better availability of open-source data, models have become cheaper, faster and more accurate than ever before.”

The WCS AI model was produced by pairing high-resolution oceanographic data with detailed in-water surveys by field scientists. The model broke the region down into 6.25km “reef cells” to identify which contained the highest numbers of fish and coral species.

“We had real data from underwater surveys gathered at many of these sites – enabling us to use data to train and test models for their accuracy,” said McClanahan.

“Now that the testing process has exposed the high strength of the models, we can use the models to predict the expected number of species even in areas where we don’t yet have data – hopefully making it easier for communities and countries to find and prioritise new protected areas.”

Not every MPA is about protecting high levels of biodiversity, points out WCS, with some created to help manage areas of importance to small-scale fishers, or to protect dwindling populations of iconic species such as dugongs.

However, it says that pinpointing the location of country’s biodiversity hotspots is important in implementing global objectives, such as the 30×30 target to protect and conserve at least 30% of lands and waters globally by 2030.

‘Experts’ and anecdotes

“We found that among the highest biodiversity locations in these 11 countries, many were not protected at all,” said McClanahan. “Most MPAs don’t have sufficient data to back up their designation.” He said that many were designated on the basis of “expert opinion” and observational anecdotes rather than data and models.

“What’s often lacking is real data telling us: Where are the highest-biodiversity areas in each country? Which places will be the most climate-resilient? Which areas do people like fishers rely on the most for food and income? Those are the types of data that we need in order to make the best decisions. This new model advances the ability to make the right decisions.”

The study was completed with the support of a grant from the US Department of Interior and Agency for International Development, and is published in Conservation Biology.

Also on Divernet: Coral sanctuary revealed in Indian Ocean, Why every blue contains a bit of fin whale, The world’s coral reefs are bigger than we thought…, Ocean Census targets 100k unknown marine species