International conservation bodies have expressed their concerns about Norway’s decision to become the first country in the world to authorise deep-sea mining.

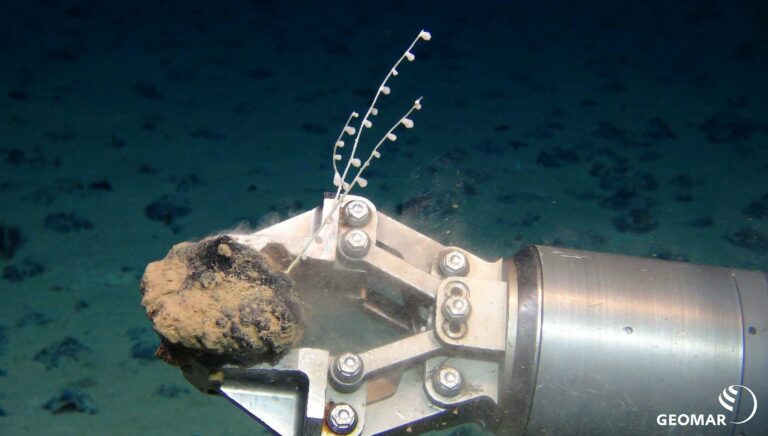

Not content with the damage to its reputation sustained by its long-term support for whale-hunting, the Scandinavian country decided on 9 January that it would also take a proactive stance on seabed mining. The decision is expected to speed up exploration for those minerals, including precious metals, now in high demand for green technologies.

Greenpeace called it a “shameful day” for Norway. Frode Pleym, head of Greenpeace Norway, criticised the country for positioning itself as an “ocean leader” while at the same time approving potentially destructive activities in Arctic waters.

The Environmental Justice Foundation (EJF) stated that the decision would act as “an irrevocable black mark on Norway’s reputation as a responsible ocean state”. Chief executive and founder Steve Trent warned of severe impacts on ocean wildlife if the mining went ahead, while campaigner Martin Webeler described the move as “catastrophic”.

Criticising the Norwegian government for disregarding scientific advice on the matter, Webeler suggested that mining companies should be focusing on preventing environmental damage in their current operations, rather than opening up a new industry.

PM called out on mining

The Deep Sea Conservation Coalition, which includes international bodies such as WWF and Fauna & Flora as well as Greenpeace, has called out Norway’s prime minister Jonas Gahr Støre for his claims that deep-sea mining can be carried out without harming oceanic biodiversity.

However, WWF’s No Deep Seabed Mining Initiative expressed a “small glimmer of hope” that extraction licences would still require Norwegian parliamentary approval – an amendment added after the strong international pushback.

Within the country itself, the Norwegian Institute of Marine Research has accused the government of extrapolating the conclusions of studies carried out in small, controlled bodies of water to larger areas.

It estimates that 5-10 further years of research could be needed to understand the potential impact of mining on marine life. Conservation activists have protested about the decision outside Norwegian embassies in at least 20 countries.

The controversial decision was made in the Norwegian parliament with an 80% majority vote, despite the concerns expressed internally and opposition expressed by the EU and the UK, which have called for a temporary ban on seabed mining.

The move initially applies to Norwegian waters, exposing an area larger than Britain – 280,000sq km – to mining, but an agreement on deep-sea mining in international waters could follow later in the year.

Minke whale toll

Meanwhile Norway continues to carry out commercial whaling even in the face of falling demand, as it hunts minke whales under a self-allocated quota – 580 were slaughtered in 2022, many of them pregnant females.

The Norwegian government, which subsidises the industry, has expressed its ambitions to boost domestic demand for whale meat as well as its exports to the world’s other whale-hunting countries Japan, Iceland and the Faroe Islands.

The International Whaling Commission’s global ban on commercial whaling came into effect in 1986, but Norway has killed more than 15,000 whales since then, typically using slow-working grenade harpoons.

Also on Divernet: Most life in deep-miners’ target zone new to science, Beginning of the end for whaling?, What difference will High Seas Treaty make?