DIVING NEWS

Sticky excretions from oceanic bacteria are glueing plastics particles together to form larger masses, according to research by Heriot-Watt University in Edinburgh.

Also read: Ghost-fishing means plastics infest deep coral

The bacteria are found in all marine and freshwater environments, but only recently have scientists discovered the effect that the biopolymers they excrete have on the nano and microplastics now found in waters all over the world.

The researchers carried out laboratory experiments using water collected from the Faroe-Shetland Channel and the Firth of Forth, incubating plastics particles in conditions designed to simulate the ocean surface.

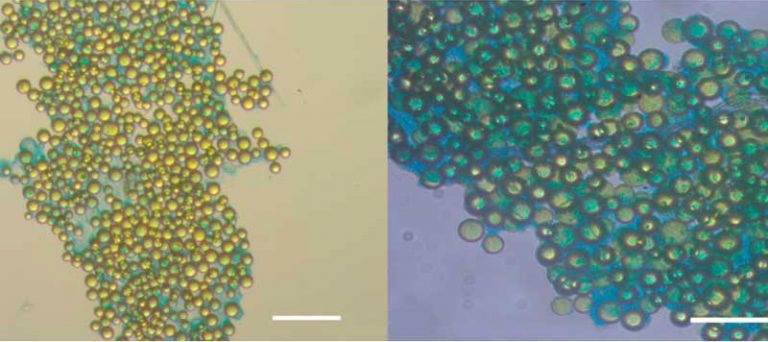

They reported that it took only minutes for the plastics to become grouped together with bacteria, algae and other organic particles, and were surprised to find that it was large masses of biopolymers that formed the bulk of these plastic agglomerates.

When the biopolymers engulfed the nanoplastic particles, which are 100-200 times smaller than a bacterial cell, the resulting agglomerates became visible to the naked eye, which the researchers believe makes small marine animals more likely to regard them as food.

The findings emerged from a £1.1 million project funded by the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) called RealRiskNano, which also involves researchers from Plymouth University.

“The agglomerates form in something similar to marine snow, the shower of organic detritus that carries carbon and nutrients from the surface to the ocean floor and feeds deep-sea ecosystems,” said microbial ecologist Dr Tony Gutierrez of Heriot-Watt, who led the study.

“It will be interesting to understand if nano- and micro-scale plastics of different densities could affect the food flux from the upper to lower reaches of the ocean.”

Heavier plastics could drive the snow to fall more rapidly to the seabed, while the opposite could happen if lighter forms of plastics became more buoyant, so starving deep-sea ecosystems.

The scientists don’t think their discovery is necessarily bad news, however.

“The discovery and characterisation of nano- and microplastic agglomerates increases our understanding of how these particles behave within the environment and how they interact with marine organisms,” said Prof Ted Henry, leader of the RealRiskNano project.

“The agglomerates are much more complex than simple pieces of plastic. Research like this is beginning to fill the gaps in scientists’ knowledge, but we need more evidence in order to prioritise and manage plastic pollution effectively.”

The research is published in the Marine Pollution Bulletin.