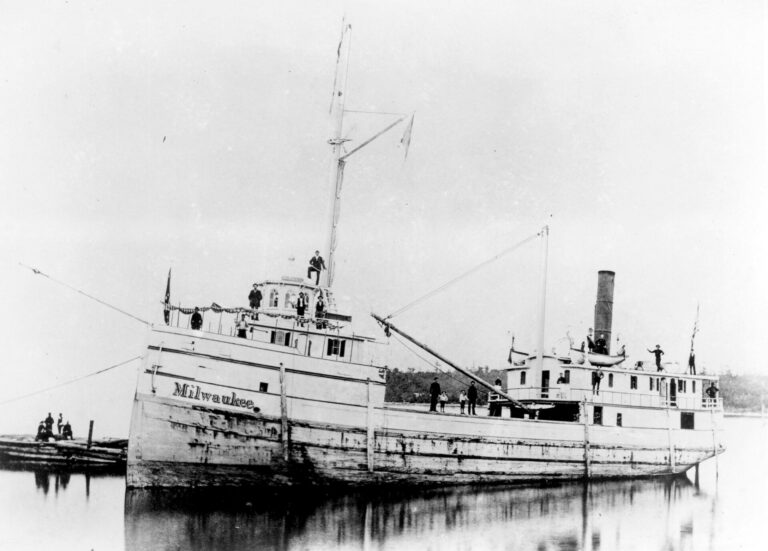

The “remarkably intact” steamboat Milwaukee, lost in Lake Michigan after being rammed in 1886, has been discovered at a depth of 108m – but although ROV dives and archive-trawling have identified the vessel, it didn’t look the way its finders had expected.

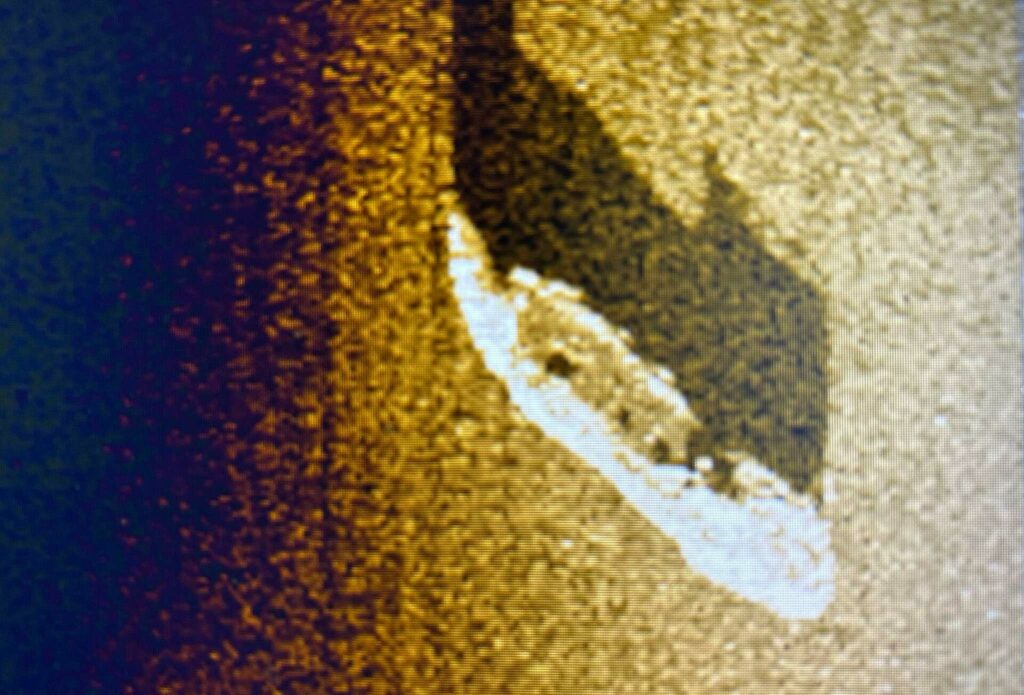

Michigan Shipwreck Research Association (MSRA) members had waited for the occasion of their annual film festival to announce the discovery to a live audience in the town of Holland, some 60km from where the Milwaukee showed up on their side-scan sonar last June.

It was the 19th wreck found in the West Michigan part of the lake by the team, who share their discoveries with the public through books, articles, presentations and museum exhibits.

Last summer they had filmed the wreck from an ROV built specially for the project by member Jack van Heest, who co-ordinated the search effort with his wife Valerie.

Northern Transportation Co (NTC) of Ohio, an early Great Lakes steamship operator, had commissioned Milwaukee in 1868 to join its growing fleet of steamers carrying settlers and supplies west from New York towards Chicago. The vessel’s story was pieced together by the MSRA team.

The 40m three-deck boat had been designed to fit through the Welland Canal locks between Lakes Ontario and Erie, and ran regularly on four of the five Great Lakes. By the 1880s, however, the expanding railways and enlarged canal locks were starting to render the NTC fleet of relatively small boats obsolete.

Some of the passenger steamers were repurposed as barges by removing the upper-deck accommodation, enabling them to pack in more cargo such as lumber, iron, fruit or packaged goods.

New career

The Milwaukee was sold and converted in this way to start a new career on Lake Michigan in 1881. In 1883 Lyman Gates Mason of Muskegon bought the boat to haul its lumber to Chicago and at that time, though no photographs remain, it was described as having only one deck.

In the late afternoon of 9 July, 1886 the Milwaukee unloaded in Chicago and set off back to Muskegon. Later the almost identical boat C Hickox, belonging to another lumber company, left Muskegon for Chicago towing a barge, both vessels fully laden.

At midnight the two boats were bearing straight down on each other off Holland, and it was Milwaukee look-out Dennis Harrington who first spotted the other vessel’s approaching lights.

Milwaukee’s Captain Armstrong and C Hickox’s Captain O’Day were alerted. Navigational rules demanded that both vessels should slow, steer to starboard and sound their steam whistles, but neither captain slowed down because they considered the visibility fine at that moment.

Thick fog suddenly rolled in, however. As Captain O’Day ordered a turn he found the whistle broken, and Captain Armstrong took no action until a break in the fog showed the C Hickox bearing down fast on Milwaukee, but his order to turn came too late.

The C Hickox rammed the other boat, popping its hull planks and sending Harrington into the lake before continuing on its way.

After the collision

As water poured into Milwaukee the captain sent a distress signal and ordered the pumps turned on and a sail to be stretched over the break in the hull to stem the inrushing water.

Several crew escaped in the lifeboat and met the C Hickox, the crew of which had been struggling to find Milwaukee.

Another steamer, the City of New York, responded to the distress call and joined C Hickox to prop up the Milwaukee between them while the rest of its crew made their way to safety, but almost two hours after the collision the boat went down by the stern.

“News accounts of the accident, as well as the study of water currents, led us to the Milwaukee after only two days’ searching,” said Neel Zoss of the MSRA, who first spotted the wreck on the sonar screen.

In what was described as excellent visibility, the team saw the boat’s forward mast still standing as van Heest piloted his ROV down.

Milwaukee sat upright facing north-east, the direction in which it would have been heading that night, but the researchers were surprised to see that the pilothouse looked nothing like the octagonal version in an older photograph of the boat.

“In studying the video, we realised that Lyman Gates Mason, who owned the Milwaukee, had made both the pilothouse and the aft cabin smaller in order to maximise the amount of lumber the ship could carry on each run,” explained another MSRA member, Craig Rich. No records have been found referring to the later adaptation.

Both captains had their licences suspended for not slowing down as the incident unfolded.

Also on Divernet: Early schooner found in Lake Michigan, Tech-divers’ dream: 150-year-old masts-up schooner, Lake wreck discovery can’t explain captain’s odd behaviour, Atlanta wreck identified in cold Lake Superior