“I was dubious about doing this, but then I thought to myself: if it saves even one person or stops one accident happening, then it’s worth it.”

Those are the words of Adam Dent, who survived a dive that left his two friends dead on the wreck of HMS Scylla in 2021. He has now decided to speak at length about his experiences on Dom Robinson’s Deep Wreck Diver YouTube channel.

In late 2022 an inquest was held into the deaths of master scuba diver trainer Andrew Harman, 40, and rescue diver Mark Gallant, 49, on the 23m-deep wreck off Plymouth the previous year. It was reported on Divernet under the headline Line-Laying Might Have Avoided Scylla Deaths.

Diving on twin-sets, the two men had been highly experienced but had run out of air after becoming trapped in the engine-room in zero visibility. Silting had become a problem inside the 113m four-deck frigate over the past decade. At the inquest the coroner had called for a national safety protocol on wreck-penetration.

At 24, Dent had been younger than the other divers but was also experienced, working as an instructor at the same dive-centre.

He told the inquest that although no line had been laid he had assumed that Harman, leading the dive, had known where he was going. Dent and the others were also well aware of the series of cut-outs on the artificial reef, designed to provide convenient exit-points for divers.

“I believe this is the first time that he’s spoken publicly about what happened,” says Robinson of the new interview. “He’s remarkably honest about what happened, and also talks about the aftermath.”

Black blob

In the video, which contains footage of the Scylla‘s interior in clear conditions, Dent explains that the three men had entered the wreck without a specific plan. They had made their way down into the engine-room on deck three, which Dent had not explored before, without laying a line.

They had realised that something was wrong when they reached a dead end, turned and were no longer able to find their way out in the poor vis.

After some time spent searching together, Dent had decided to go his own way, hoping to find an exit while he still had enough air to be able to tie his reel in and go back for the others.

He describes the passage of time as he felt his way around, aware of his air supply getting lower and his breathing rate threatening to get out of control – and explains why he decided that if it came to it he would prefer to die alone.

His salvation came when in the midst of the brown-out he was able to make out “a black blob” above him – a hole with bars across that he could squeeze through by removing his cylinders to reach one of the cut-outs.

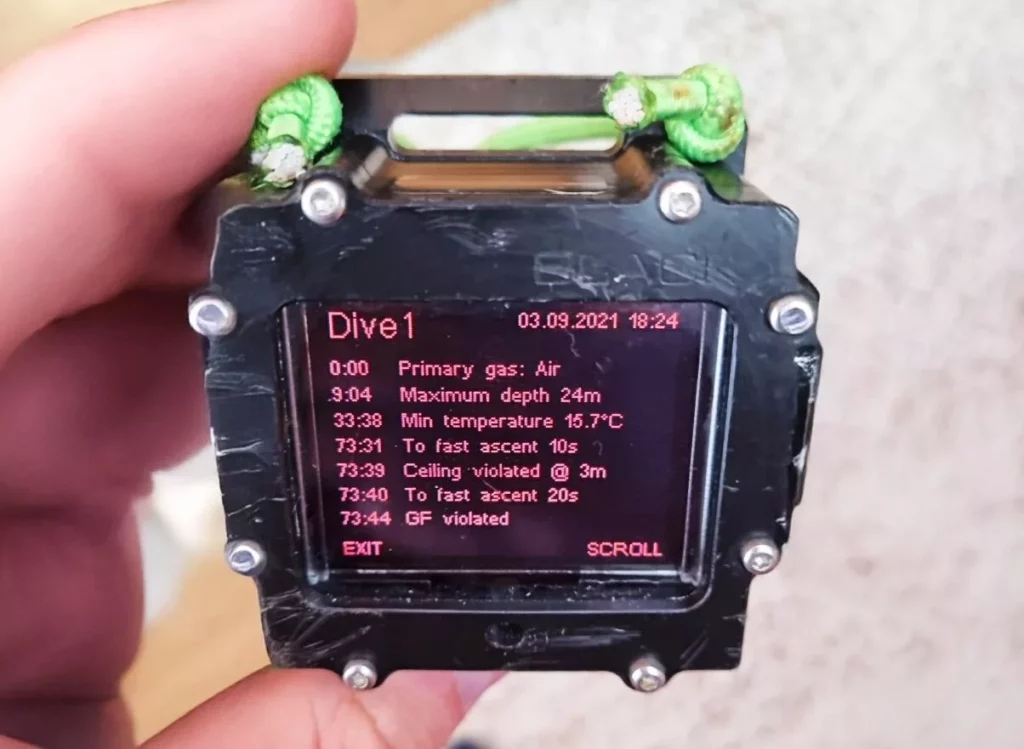

Rapid ascent

Dent talks about why he made a rapid ascent despite having spent most of 74 minutes at depth, and his experience back on the dive-boat before being taken to the hyperbaric chamber. Even going home was unsettling: “Stuff was happening to me and I was just along for the ride.”

He discusses the perils of complacency, survivor’s guilt and the factors he believed saved his life: the fitness that assisted with his air consumption; being equipped with a wetsuit, sidemount cylinders and an umbilical torch; and how the support of friends and the diving community helped him to avoid post-traumatic stress.

Robinson describe’s Adam Dent’s story as “a vital lesson in survival, risk-management and the unforgiving nature of overhead environments”.

And, surprisingly, it turns out that not only is Dent still diving but he would willingly dive the Scylla again: “I think that would be a weird dive – but maybe cathartic.”

Sadly a text book example of why you’re never too experienced to follow basic protocols, simply having laid lines would almost certainly have avoided this tragedy. Zero viz, “Braille” diving even in open water can be disorientating and risky, in a confined environment it is all too often deadly.

Unfortunately, so many reasons this dive went wrong. He is one lucky young man.

It seems absolutely insane to dive in any enclosed spaces without a line.

How many times will we see videos where even highly experienced divers died because they failed to deploy the most vital tool in their kit?

Its like getting onto a T.T race bike withouta helmet or leathers.

Just WHY???

Successfully getting home to the family requires us all to eliminate as many risks as possible…