It comes in handy for slicing bone as the sharks age, and reflects how their lifestyle changes over time, as EMILY HUNT, DAVID RAUBENHEIMER and EZEQUIEL M MARZINELLI of the University of Sydney explain

A great white shark is a masterwork of evolutionary engineering. These beautiful predators glide effortlessly through the water, each slow, deliberate sweep of the powerful tail driving a body specialised for stealth, speed and efficiency.

From above, its dark back blends into the deep blue water, while from below its pale belly disappears into the sunlit surface.

In an instant, the calm glide explodes into an attack, accelerating to more than 60kmph, the sleek torpedo-like form cutting through the water with little resistance. Then its most iconic feature is revealed: rows of razor-sharp teeth, expertly honed for a life at the top of the food-chain.

Scientists have long been fascinated by white shark teeth. Fossilised specimens have been collected for centuries, and the broad serrated tooth structure is easily recognisable in jaws and bite-marks of contemporary sharks.

But until now surprisingly little was known about one of the most fascinating aspects of these immaculately shaped structures: how they change across the jaw and to match the changing demands throughout the animal’s lifetime. Our new research, published in Ecology And Evolution, set out to answer this.

From needle-like teeth to serrated blades

Different shark species have evolved teeth to suit their dietary needs, such as needle-like teeth for grasping slippery squid; broad, flattened molars for crushing shellfish; and serrated blades for slicing flesh and marine mammal blubber.

Shark teeth are also disposable – they are constantly replaced throughout their lives, like a conveyor-belt pushing a new tooth forward roughly every few weeks.

White sharks are best known for their large, triangular, serrated teeth, which are ideal for capturing and eating marine mammals like seals, dolphins and whales.

But most juveniles don’t start life hunting seals. In fact, they feed mostly on fish and squid, and don’t usually start incorporating mammals into their diet until they are roughly 3m long.

This raises a fascinating question: do teeth coming off the conveyor-belt change to meet specific challenges of diets at different developmental stages, just as evolution produces teeth to match the diets of different species?

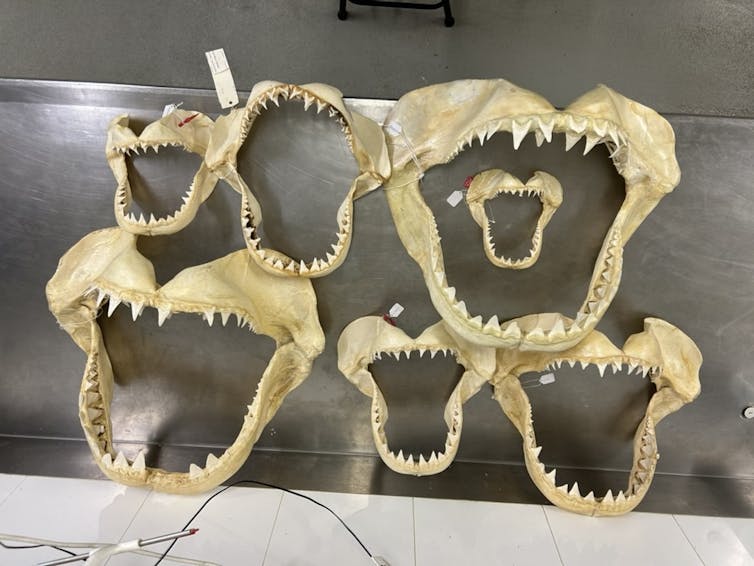

Previous studies tended to focus on a small number of teeth or single life stages. What was missing was a full, jaw-wide view of how tooth shape changes – not just from the upper and lower jaw, but from the front of the mouth to the back, and from juvenile to adult.

Teeth change over a lifetime

When we examined teeth from nearly 100 white sharks, clear patterns emerged. First, tooth shape changes dramatically across the jaw. The first six teeth on each side are relatively symmetrical and triangular, well-suited for grasping, impaling or cutting into prey.

Beyond the sixth tooth, however, the shape shifts. Teeth become more blade-like, better adapted for tearing and shearing flesh.

This transition marks a functional division within the jaw where different teeth play different roles during feeding, much like how we as humans have incisors at the front and molars at the back of our mouths.

Even more striking were the changes that occur as sharks grow. At around 3m in body length, white sharks undergo a major dental transformation. Juvenile teeth are slimmer and often feature small side projections at the base of the tooth, called cusplets, which help to grip small slippery prey such as fish and squid.

As sharks approach 3m, these cusplets disappear and the teeth become broader, thicker and serrated.

In many ways, this shift mirrors an ecological turning point. Young sharks rely on fish and small prey that require precision and an ability to grasp the smaller bodies. Larger sharks increasingly target marine mammals: big, fast-moving animals that demand cutting power rather than grip.

Once great whites reach this size, they develop an entirely new style of tooth capable of slicing through dense flesh and even bone.

Some teeth stand out even more. The first two teeth on either side of the jaw, the four central teeth, are significantly thicker at the base. These appear to be the primary “impact” teeth, taking the force of the initial bite.

Meanwhile, the third and fourth upper teeth are slightly shorter and angled, suggesting a specialised role in holding onto struggling prey. Their size and position may also be influenced by the underlying skull structure and the placement of key sensory tissues involved in smelling.

We also found consistent differences between the upper and lower jaws. Lower teeth are shaped for grabbing and holding prey, while upper teeth are designed for slicing and dismembering – a co-ordinated system that turns the white shark’s bite into a highly efficient feeding tool.

A life-story in teeth

Together, these findings tell a compelling story.

The teeth of white sharks are not static weapons but living records of a shark’s changing lifestyle. Continuous replacement compensates for teeth lost and damaged but, at least equally important, enables design updates that track diet changes through development.

This research helps us better understand how white sharks succeed as apex predators and how their feeding system is finely tuned across their lifetime.

It also highlights the importance of studying animals as dynamic organisms, shaped by both biology and behaviour. In the end, a white shark’s teeth don’t just reveal how it feeds – they reveal who it is, at every stage of its life.

Emily Hunt, PhD Candidate, School of Life & Environmental Sciences; David Raubenheimer, Leonard P Ullman Chair in Nutritional Ecology, Nutrition Theme Leader Charles Perkins Centre, Chair Sydney Food & Nutrition Network; Ezequiel M Marzinelli, Associate Professor, Faculty of Science, all University of Sydney. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence. Read the original article.