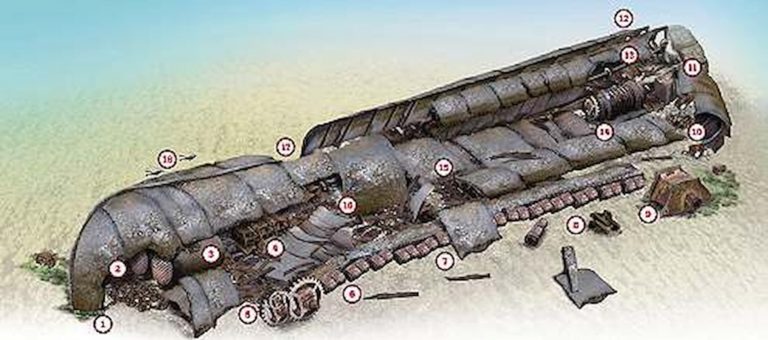

The St Dunstan is a rather nice but often overlooked bucket-dredger, says JOHN LIDDIARD. It sank in Lyme Bay in 1917, after striking a mine. Illustration by MAX ELLIS

MOST SKIPPERS CONSIDER THE ST DUNSTAN a difficult wreck to shot. The only bit that really sticks up is the keel under the bow, rising a good 5m from the seabed at 29-30m, so this month’s tour begins right on the bow (1).

Hull plates have fallen away along both sides of the upturned hull, with the better access to the interior being on the starboard side. A large pile of debris just inside the wreck is mostly the anchor chain (2), with some scraps of other wreckage and the anchor winch buried underneath. The St Dunstan is usually teeming with fish, with writhing shoals of huge pouting inside the wreck and some big pollack above.

Immediately behind this pile of chain is something that came as a total surprise to me the first time I dived the St Dunstan, but was pretty obvious once I considered the engineering of a bucket-dredger. A pair of enormous boilers stands right at the front of the wreck (3).

It is probably these boilers that are holding up the rest of the wreck above them. They and engines are at the front of the ship to make room for the dredging machinery further aft.

There is a choice of routes aft, either around the outside of the starboard boiler or between the two boilers to the engine room. On the inside, you will find some very big conger eels living in this area.

The starboard engine (4) is upright and resting upside-down on a pile of debris. Further inside the upturned hull, the port engine is upright and hanging from its mounts.

Leaving the engine-room machinery alone for a while, just off the starboard side of the wreck is a set of enormous gears (5), part of the drive machinery for the dredge system. One of these is still attached to the top of the chain of dredge-buckets (6).

Easily one of the more robustly built parts of the St Dunstan, the arm and bucket assembly has fallen clear of the hull and is pretty much intact, lying on one side and leading towards the stern. There is a slight bend near the top of the arm, then about halfway along it is partly covered by a hull plate (7).

A few buckets before the end of the arm and just out from it, a large pulley block (8) is part of the mechanism used to raise and lower it.

Just off the end of the arm is an upside-down scoop, several times the size of the individual dredge-buckets (9). This would have been the business end of the dredging mechanism.

The rounded stern of the wreck is only a few metres away, lying on its port side (10). The interior has collapsed, leaving just the shell of the stern to swim through where it has broken clear of the twin keels.

‘Below’ the stern, a single rudder lies resting flat on the seabed (11), guarding the two keels and propellers (12). The port keel is completely inverted, and the starboard keel has collapsed towards it. The hull of the St Dunstan would have had a well in the middle for the dredge arm to be lowered, with one keel running either side of the well.

This begs the question of whether there was only a single rudder, or whether a second one is buried somewhere beneath the wreckage.

Heading back towards the bow, the starboard keel is broken open, making it possible to follow the propeller-shaft forward (13).

The final part of the dredging mechanism is a large winch drum (14), used to raise and lower the dredging arm. This is still tightly packed with cable and on one end is another pair of big gears, which would have driven the winch from one of the main engines.

The propeller-shaft continues forward along the broken-open keel and back inside the wreck (15), ending in the engine room with a bevel gear (16).

Whereas most steam-driven ships would have had no gearbox, with the engine driving directly onto the propeller-shaft, on the St Dunstan the main engines would also have been used to power the dredging mechanism, hence the need for elaborate gear systems.

Only a small section of hull remains intact, leaving an arch through to the port side (17). Other gears are on the end of the engines and scattered about below this swim-through, where the gearboxes have fallen apart.

The port side of the bow (18) is a bit more intact than the starboard side, with missing hull plates leaving windows to the inside of the wreck, small clumps of anemones and dead men’s fingers on the exposed ribs. There is one particularly large hole close to the bow and a few metres above the seabed. Perhaps this was where the mine exploded.

Thanks to Izzy Imset and other members of the DIS team.

PRESSED INTO ACTION

Some idea of the threat to Britain’s survival in World War One caused by German torpedoes and mines can be gained from the fact that the 200ft-long St Dunstan, built as a bucket-dredger in 1894, had to be requisitioned and pushed into service as a mine-sweeper. Practically anything that could float was taken by the Admiralty to keep the shipping lanes clear, writes Kendall McDonald.

The St Dunstan was lost on 23 September, 1917. She was sunk by a mine laid by UC21 on that U-boat’s last mission, which had started from Zeebrugge on 13 September, and from which Oberleutnant von Zerboni di Sposetti and his crew of 26 never returned.

St Dunstan had been taken over by the Navy, and though her civilian captain Thomas Morgan was still aboard, she was commanded by Sub-Lieutenant Charles Gray. He took her out of Portsmouth early on the day of the sinking and headed down-Channel. He had to anchor in Weymouth Bay with steering problems, but soon sorted that out and headed on past Portland Bill with his two escort trawlers, Fort Albert and Horatio.

At 11.30am, a huge explosion on St Dunstan‘s port bow caused her to list violently and Lt Gray ordered his men to jump overboard. He flung lifebuoys to them before jumping into the sea himself. Four minutes later the ship turned turtle and sank.

Lt Gray and 19 of the 21 men aboard were picked up by the trawler escorts, but first mate John Obery and deckhand Edward Warren were drowned. Some of the survivors thought that they had been torpedoed, but later, when the area was swept, five U-boat-laid mines were found and identified as being from UC21.

TOUR GUIDE

Tides: Slack water is 3.5 hours after high water Portland and 3.5 hours before high water Portland.

Getting there: For Weymouth, follow the A37 or A354 to Dorchester, then the A354 to Weymouth and on to Portland via A354, turning left for the old Castletown dockyard as the road starts to climb the hill to Portland. Breakwater Diving is located at the Aqua Sport Hotel, on the left as you get to Castletown.

How to find it: The GPS co-ordinates are 50 38.291N, 002 42.062W (degrees, minutes and decimals). There are no convenient transits, so you have to search with a GPS and echo-sounder. The bow lies to the south-west.

Diving and air: Top Gun, booked through Breakwater diving centre (01305 860269/ 860670. Also see DEEPSEA UK Website for charter boats.

Launching: Slips are available at Weymouth, Portland, West Bay and Lyme Regis. Note that harbour and launch fees are payable.

Accommodation: The most convenient is at the Aqua Sport Hotel (01305 860269). Further afield, the area is littered with B&Bs and small hotels. Campsites are out of town, usually very smart and on the expensive side.

Qualifications: Suitable for sport divers and at an ideal depth for extending bottom time with a nitrox mix.

Further information: Admiralty Chart 3315, Berry Head to Bill of Portland. Ordnance Survey Map 194, Dorchester, Weymouth & Surrounding Area. Dive Dorset, by John & Vicki Hinchcliffe. The Diver’s Guide to Weymouth & Portland Area, Weymouth & Portland BSAC. Tourist information: Weymouth 01305 785747, Lyme Regis 01297 442138.

Pros: A very different kind of wreck, and one of the less-dived in Lyme Bay.

Cons: The St Dunstan is a small wreck and it doesn’t take many divers to make it feel crowded.