A new book called The Airplane Graveyard has got us all excited in the DIVER office, so here are two extracts to give you a flavour of the very unusual diving in Kwajalein. BRANDI MUELLER, who wrote it with historian Alan Axelrod, tells the story.

Also read: Photographic expansion at Diving Talks

DIVING THE WRECKS

WHAT A STRANGE THING, seeing airplanes under water. You expect ships to end up under water someday. Challenge nature by riding the sea, and you chance being swallowed. But planes belong in the air.

True, what goes up must come down to Earth again, and 71% of the planet is covered by water. That some aircraft will end up under the sea is inevitable. Yet, the sight of submerged aircraft, arrested in time, seems almost mystical to me.

In other words, the Airplane Graveyard of Kwajalein Atoll is mind-blowing for a scuba-diver.

On a morning like many others on Roi-Namur – Roi for short – a few of my dive-buddies and I head out into the lagoon in a rented boat. We’ve biked from our quarters on one side of the island to the marina, dragging behind us small trailers filled with scuba gear, cameras, water, snacks and plenty of sunscreen. There is no wind, and the sun is already unrelenting. Tropical heat and humidity are pretty much a year-round thing on Kwaj, but this is summer, the doldrums, in which wind is a rarity.

The celebrated trade winds of this part of the world are creatures of the winter months, and they feel welcome – though they make it harder to pedal a bike and they can whip up enough waves to make diving impossible. So, today, we try not to complain about the heat. Anyway, we’ll be under water soon.

We load the boat with dive and emergency gear: GPS, marine radio, life-jackets, first-aid kit, fire-extinguisher and a pair of paddles.

We drive the loaded boat to a small dock on the other side of the harbour and load up scuba tanks.

If you think serious (as in living) divers are happy-go-lucky and devil-may-care, you would revise your thinking if you saw us double-check everything before setting off on the dive. Right now, each of us wants to avoid embarrassment.

Forget a mask, and you’ll not only miss out on diving, you’ll endure jokes at your expense that won’t end until someone else does something worthy of new jokes. But the checking and double-checking are part of an awareness that, under water, life depends on your gear and your vigilance.

The wind stirred by the speeding boat feels great. After about 20 minutes I slow down as we approach the dive-site. Once we’re over the point marked on the GPS, we throw in an anchor. That secured, we throw another, which we will set once we’re under water, to make sure the boat doesn’t drift away and run aground on the nearby reef while we’re below.

Gear on, I sit on the edge of the boat. With one hand, I hold my regulator in my mouth and my mask in place. My other hand is behind my head for protection. I look behind me once more to make sure it’s clear back there, and I back-roll off the six-passenger boat and into the bathwater-warm lagoon.

The temperature is only a slight relief from the punishingly hot Equatorial air. Our successive splashes ripple the still water. Once everyone has signalled OK, we start our descent together, letting air out of our BCs to slowly sink into the blue.

The clear water is lit by sunshine even as we make our way to 30m. I scan the area for a shadow – anything different from blue.

As we near the sand, I see off in the distance the shadow I’m looking for. Pointing, I turn to my buddies, who are also pointing. They’ve spotted it, too.

We go deeper and towards the shadow, which gradually morphs into the shape of a nose-down airplane. It looks as if it crashed straight up and down into the ocean floor, propeller dug into the sand.

From the looks of it, the “crash” could have happened yesterday. The aircraft is in fantastic condition – very much intact.

Why? Because it did not crash – not yesterday and not some seven decades ago. It was dumped from a barge.

Today, we are diving one of the most popular planes in the Airplane Graveyard, the Vought F4U Corsair. During its production, which began with prototypes in 1940 and ended in 1953 when final models were delivered to the French, 12,571 F4Us were manufactured. Yet this is the only Corsair in the graveyard.

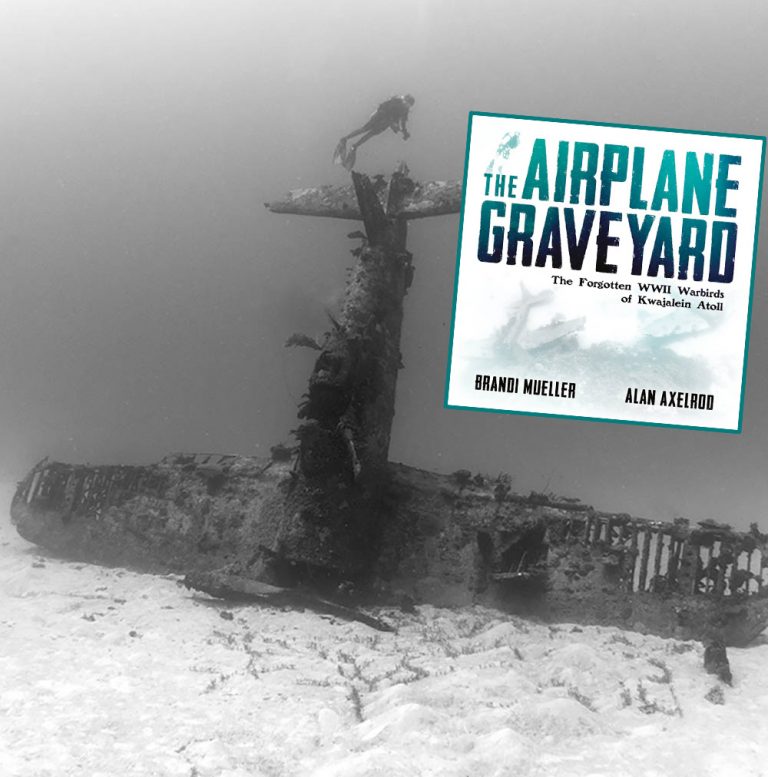

Fortunately, because it landed nose-down in the soft sand (see main image, top) and in a spot where there is nothing but clear water and clean sand as far as the eye can see, it is among the most photogenic planes.

We get closer. Looking down from the tail, we see that the wings are bent a little and curved upward.

This isn’t damage. The F4U wing is a gently inverted “gull-wing”, which allowed engineers to design short landing gear, sturdy enough to take the repeated punishment of hard pancake landings on the limited space of an aircraft-carrier.

The gull shape also allowed the wings to be folded up more easily. Even in WW2, aircraft-carriers were big ships, but space was nevertheless at a premium. Folding wings were indispensable to efficiently storing aircraft, whether on deck or on the hangar deck below.

After some 70 years in salt water, this Corsair has suffered astoundingly little erosion of the aluminum, although some of it is blanketed in a lichen-like sponge, yellow or red wherever you shine a light on it.

Incongruously, a spare propeller sits in the cockpit where a pilot should be. This is a common feature of a lot of the planes in the graveyard. Presumably, the props were taken off many of the planes to make them easier to load for their final voyage on the funeral barge.

The prop on this aircraft, however, was not removed. It is partly buried in the sand. The one it carries in its cockpit belongs to some other plane or was a spare part deemed to be trash in October 1945.

The cockpit and the area surrounding the spare propeller are covered with schooling glassfish, tiny, orange, swarming so tightly that they block the view of whatever is behind them.

They are a moving curtain. Sweep your hand near them, and they move away in perfect unison, only to coalesce again as soon as your hand is gone.

Then there are the lionfish, incredibly showy in red and white and black with spiky, venomous fin-rays. They love areas where propellers rest in the sand.

Three or four can almost always be seen, sometimes resting right on the prop-blades. When they get hungry, they move upward just a bit to partake in the cockpit buffet of glassfish.

There are more planes near the Corsair, but most are a good five-minute swim away or longer. We’ve spent almost all our bottom time on the Corsair, and our computers are telling us it’s time to start going shallower. So we swim a little way up the sand slope close to the barrier reef and see two SBD Douglas Dauntless aircraft sitting upright in the sand at about 18m.

One is mostly buried, probably due to sand shifting during strong weather. Yet it is one of the planes down here that makes me think you could just brush off the sand, start it up and take off – returning to the sky directly from the lagoon floor.

It’s a nice thought, but we continue our ascent, stopping at 5m for a three-minute safety stop. Even after that time passes, we make our way to the surface and the sunshine unhurriedly.

THE AVENGER

OVER THE PAST FEW YEARS, several news outlets have misreported that I “discovered” the Airplane Graveyard. Obviously, I did no such thing. The site has been well-known to people living on Kwaj since the planes were dumped in 1945, and divers have visited at least as far back as the 1960s.

True, the difficulty of gaining access to the diving in Kwajalein Atoll has kept many away. But the graveyard is not a secret.

While I never claimed to have discovered the Airplane Graveyard, there is one plane there to which I might have a discovery claim. I may not have been the first to see it – I don’t know – but it was not recorded on the extensive GPS listing maintained by the Roi Dolphins Scuba Club.

My friend Dan and I came across it when we were diving between my scheduled ferry runs. My shift schedule imposed a hard limit on how long we could be out.

It was a little windier than we’d have liked. In fact, a smarter pair would probably not have been diving that area in those conditions, because the wind made the water choppy.

As the graveyard area is mostly sand, anchoring the boat securely can be iffy, particularly on choppy days.

Dan and I had been on a mission to dive all spots in the GPS-listed graveyard, and that day we chose a mark neither of us had been to.

I was driving the boat, pulled up to the spot, and Dan threw the anchor. Then we waited. And waited.

We watched the GPS to see if our distance from the target moved, indicating that we had not hooked the anchor and were being dragged by the wind. Most of the airplanes are very close to the shallow barrier reef encircling the lagoon. If the boat drifted while the divers were under water and ran aground on the reef, that would be a bad thing for many reasons.

In this case, the most significant peril I could think of was not getting back to the ferry on time.

According to the GPS, we were slowly moving farther away from our target, 30m, 45m … 60m. The GPS kept going.

I had Dan hoist the anchor, and I drove back to the GPS mark. He threw the anchor again, and we waited.

And, again, the GPS moved. Time was ticking. The more time we spent hooking up, the less of it we had to dive.

Not wanting to haul up the anchor again, we kept waiting. At about 120m, the GPS stopped. We both looked at it and looked at each other. Well, we could swim 120m, right? That wasn’t too far.

In fact, it was quite far, especially where we were going to dive, an area subject to strong currents during tidal changes – something we hadn’t checked before coming out.

Impatience, however, is a powerful driver. Frustrated with the sand, frustrated with the wind, we were also frustrated with one another. The decision? Just go for it.

We took a compass heading on the direction toward where the plane was supposed to be, 120m behind us, and we jumped in. Maybe we would find it. Maybe not. Either way, we were finally diving, and diving is always better than working.

Being a boat captain – and having signed my name to the reservation for this rented boat – I felt a slight twinge of nerves about leaving it alone in the wind. But these dives were usually around 30m, so we’d be under water for 18-20 minutes tops before our bottom time ran out. It didn’t seem like too much could go wrong in that span.

Generally, the air temperature on Kwaj stays constant at 29°C, but the wind that day made it slightly chilly, and the water, at 28°, actually felt warmer than the air as we began our descent.

We started out facing each other, and even though we needed to start swimming south-east we also needed, first thing, to check that the anchors were secure at the bottom.

Following the anchor-lines down, we were at about 9m, still right under the boat, when I saw a shadow. A plane!

But, clearly, it wasn’t the plane, the one we were looking for – unless the GPS co-ordinates we had were incorrect.

Either way, it was a plane we had never seen. So we quickly checked the anchors, repositioned them securely, and headed to the plane.

This dive was still quite early in my graveyard adventures, so I wasn’t up on my aircraft recognition. I had no idea what type of plane I was looking at, but I did know that I really liked the look of it, sitting upright in the sand on the slope down from the reef.

The engine was broken off, positioned just in front of the fuselage, although mostly buried in the sand. The tips of the wings were also buried, but I could see that the wings were partly folded, so it had to be a carrier-based aircraft.

There was nothing but white sand all around. The cockpit was so thickly filled with glassfish that you couldn’t see the instrument panel without shooing them away. Whip corals, long, thin, and greenish, looking like long pipe-cleaners, grew off the aircraft.

There were crinoids, too, one of those sea animals that look like plants – or, in this case, like featherdusters, which is what most people call them. Their feather-like leaves ball up into a sphere and can be black, yellow or many other colours besides green.

Moorish idols, in bold white, black, and yellow, and emperor angelfish, vibrant in yellow horizontal pinstripes on a blue background, swam around the plane along with many other less showy fish species.

We also swam around this plane a few times, and when we’d seen enough we still had some bottom time left.

So we signalled to each other that we should swim further in hopes of finding the plane we were looking for – or maybe something else. We used our compasses to swim in the direction we had originally intended.

After a while, having come across nothing and with our bottom time running out, it was time to start heading to shallower waters. The current had also picked up, moving us farther away from the boat, so we started kicking harder to get back to the anchor-line.

Reaching the line, we ascended, did our three-minute safety stop, and returned to the surface.

Thankfully, the boat was still there. Our excitement – especially after that rough start – was hard to hold back. We were still unsure if what we had seen was the plane we were after or something else altogether. Either way, we were happy we had found something.

I told Dan we should mark the GPS, and jokingly suggested we call it “Brandi’s Plane.” He protested mildly, saying that he was sure it had to be on the list somewhere and that we must have just drifted over to another spot.

But in the end, grudgingly, he put the co-ordinates in, and, bringing the boat back to shore, we were all smiles.

I did my ferry run and then scurried back to my room to download the photos. I posted one on Facebook.

Minutes – and I mean minutes – after I posted, the undisputed “WW2 Airplane Guru” of Kwajalein posted a comment in response. He identified the aircraft as a Grumman TBF Avenger, a torpedo bomber developed for the US Navy and Marine Corps.

Like the other warbirds in the graveyard, the Avenger was a hero of WW2. It first flew on 7 August, 1941 and made its combat debut at the Battle of Midway (4-7 June, 1942).

Five of the six that flew during that fight were lost. But Midway turned the tide against Japan in the Pacific war, and the Avenger went on to become the premier torpedo-bomber of the war.

As for me, the Guru commented that the only other Graveyard Avenger he knew about was upside-down in the sand. This really got me excited, and Dan and I asked every diver on Roi if they had ever seen or heard about an upright Avenger. No one had.

Did this mean that Dan and I were the first human beings to dive it? Common sense tells me that someone at some time saw it but just didn’t mark it.

Well, we marked it. So, if I can take credit for finding anything, I’ll take it for this plane.

NOW READ THE BOOK…

At the end of World War Two, around 150 US aircraft, all veterans of the Pacific war, were dumped in the lagoon of Kwajalein Atoll in the Marshall Islands.

In The Airplane Graveyard Brandi Mueller has dived to capture rare images of these forgotten planes, many of them looking as if they could still take off and return to the war-torn skies at any moment.

Encrusted in coral, these haunting aircraft are now home to a colourful array of tropical Pacific marine life, including fish, turtles

and sharks.

Mueller reveals the remains of Douglas SBD Dauntless, Vought F4U Corsair, Curtiss SB2C Helldiver, Curtiss C-46 Commando, Grumman F4F Wildcats, Grumman TBF Avengers and

an astounding eleven PBJ-1 Mitchell medium bombers.

Mueller is an award-winning underwater photographer and freelance writer. She has been scuba-diving for 18 years and instructing for 12, diving all around the world both teaching and taking photos.

She is also a USCG Merchant Mariner captain, and worked as a captain in Kwajalein Atoll for more than three years while photographing The Airplane Graveyard.

The book contains 89 colour and 83 mono photographs, including historical images. They are accompanied by a text that includes an historical account of the aircraft written by military historian Alan Axelrod.

Published by Permuted Press. ISBN: 9781682617717. Hardback, 176 pages, 25 x 25cm, US $30.