Volunteer underwater search-teams make headlines in the USA, solving cold cases by finding missing persons in submerged cars, but there was no equivalent in the UK before Beneath The Surface.

With demand for his dive-team’s services soaring, PHIL JONES is wondering just what he started – and if he’ll ever find time to go wreck-diving again. In a Divernet long read, he and one of the relatives he has helped talk to Steve Weinman.

Also read: AquaEye gifted to UK dive-search volunteers

Scottish anglers Greig Stoddart and Ian McBurney had made the short boat-journey out to the island on the Gartmorn Dam artificial loch near Alloa a hundred times, probably more. They had set off on another camping trip on 22 December last year.

This time, however, the friends failed to return. With no sign of them by Christmas Eve, relatives informed the police. The island was no more than 70m out and the water relatively shallow – in summer, the men could have waded there and back.

However, strong winds had blown up in Clackmannanshire; the men were using a new, unfamiliar petrol outboard engine on their small boat, and it was assumed that they had run into difficulties on their way back.

Police Scotland’s nearest dive-team, based at Greenock on the west coast 60 miles from Gartmorn Dam, were not contracted to work over Christmas, though they were able to recover the body of 55-year-old McBurney on Boxing Day, from water less than 2m deep.

An eye-witness had seen a person struggling in the water and noted the location using a GPS app, but there was no sign of the boat, or of 44-year-old Stoddart.

Bad weather set in, the police had no sonar and were having trouble using their own boat at the site. As Christmas gave way to New Year, the missing man’s family were getting beyond frustrated.

It would take Beneath The Surface (BTS), a team of diving volunteers based 220 miles away in Lancashire, to complete the grim task – and it would be far from their only mission this year.

An earlier Christmas

Phil Jones, who started Beneath The Surface, is a 36-year-old self-employed builder from Chorley who qualified as a PADI diver in 2016.

He and his mates spent much of their time diving the North-west’s inland sites such as Capernwray and nearby Eccleston Delph until, attracted more by shipwrecks than fish, they broadened their scope to dive regularly at the likes of Anglesey and Oban.

Phil and friend John Peers, not a diver but a boatman, had got hold of a sonar scanner in the hope of discovering some wrecks for themselves.

But Phil’s wreck-diving plans, along with others such as to dive abroad, to become a technical diver or an instructor, soon had to be shelved as diving with a grimmer purpose became a priority.

That all started over another Christmas period four years ago. “We saw on Facebook that a family’s son had gone missing in a river in Cumbria,” Phil tells me.

“It had been a few weeks and they knew he was in there but two other people had also gone missing at that time, and the police just couldn’t cover everything.

“The family had raised £10,000 for a private dive company to go in, which I didn’t like the sound of – I didn’t think families should have to pay for that.

“We had the boat and the sonar to look for wrecks, and we’d been seeing a lot of things in the water like tyres and smaller objects. So we reached out to the family and said: keep the money as a back-up and let us come up and see what we can do.”

The friends didn’t find the body, as it happened – they were working upriver when it was located in a harbour.

But the seed had been sown “and it snowballed from there”, says Phil. “We thought there might be other families that needed help, so we set a page up on Facebook – but I had no idea just how busy it was going to get!”

Since that first recovery, Cumbria Search & Rescue calls Phil whenever a missing person is suspected to have ended up in water in its area – although it remains alone among the emergency services in doing that.

‘What we do is very safe, really’

Phil was familiar with the YouTube channels of US freelance dive-teams such as Adventures With Purpose and Chaos Divers. “They’re mainly looking for cars, and we don’t really have cars go missing in the same way, because we don’t have the public boat ramps.”

He is not aware of any other amateur group doing anything similar in the UK, but it wasn’t long before he and his fellow-divers realised just how often people go missing in its waters.

They continued to volunteer at weekends, responding only to direct requests from families and funding all the costs of travel, accommodation and incidentals from their weekday jobs.

Donations started to come in, but Phil had decided that these would be used purely to fund necessary equipment.

He reckons the team has been involved in more than 30 cases in the past four years, 13 of them in 2023 alone – and the requests are accelerating.

“I thought last year was busy, but this year I’m hoping that there’s going to be a respite, because at the moment it’s non-stop,” he says.

Does that indicate that the emergency services aren’t up to the task? “I’ll never criticise the police, or anyone who searches for missing persons, because it’s a very difficult job even on land, and in water it’s especially difficult,” Phil told me.

“We can operate without the same constraints that the police have, the resources, the power, the time-frames and the hoops they have to jump through. There are so few police search-teams now, and they can’t be everywhere at once.

“Police officers can want to jump into rivers to save someone but then get into trouble afterwards. Nobody should put themselves at risk and health and safety is key – though sometimes it might seem it’s a commonsense thing, when you know it’s pretty safe.

“I’d never try to encourage anybody else to do what we do because I don’t want anybody to put themselves at risk – but we don’t take any risks. What we do is very safe, really.

“Usually we’re in 4 to 6m of water with no entanglements, and we can see any trees or obstacles using the sonar before we even get in the water. So really the only consideration is that it’s usually dark water and zero visibility.”

All the same, no-vis conditions can mean that sharp scrap metal, branches, fishing-line and hooks and deep silt are all capable of providing nasty surprises.

The relatives’ view

Thomas Stoddart, a cousin of the missing Scottish angler Grieg, was less diplomatic about the role of the emergency services when he spoke to Divernet. However, for family-members like him, getting closure for the loss of a relative is always going to be a raw topic.

“It’s not about glory, it’s not about getting a medal, it’s just about bringing back loved ones for their families,” he says. “Police Scotland have told me they’re not allowed to call in outside help in case anything goes wrong.”

But, he asks, where no criminality is suspected, why can’t the police at least pass on to families a list of other people who might be able to help?

“We need to make changes. The police dive-team were looking for three weeks for my brother, but they’re only contracted for eight hours a day from Monday to Friday, so by the time they’d travelled from Greenock to Gartmorn Dam every day they were only getting a maximum of an hour and a half in the water,” says Thomas. “They’re restricted by funding and also by politics.”

The search for Greig Stoddart was plagued by bad weather and lack of a suitable police boat, he says, claiming that what diving took place was generally within 10m of the shore.

“I was up there all day and every day. It became a routine – we’d come up every morning, sometimes 20 of us, with waders on, stand side by side and walk out as far as we could, in case Greig had been washed in towards the side. I told the police there was no point diving so close in, because we’ve already swept this area.”

He then took to spending hours dredging the water using a 6m pole with hooks attached. “The frustrating thing was that there were no major rivers coming in, no major outlets, no undercurrent whatsoever. It’s just a pond. It should have been like a real-life training exercise for the police.”

Growing desperate, Thomas took to social media and local press to argue that the police searches were unacceptable – and that led him to reach out to Phil Jones, who offered to come straight up with his team. That meant a 4am start on a day on which the police divers would not be working: New Year’s Day.

The police could not allow anyone else to dive in the area – standard practice before they could rule the site out as a possible crime scene – but there was nothing to stop Phil taking out the boat and sonar.

“We got a really good hit, which looked like a boat to me,” says Thomas. “There’s not going to be many boats or boat-shaped objects in Gartmorn Dam, because it was drained in 2018 and everything taken out.”

Phil watched the police divers continue their work on 2 and 3 January which, according to Thomas, involved a diver on a rope being drawn along by a boat in zero visibility. Phil told the police that although he couldn’t dive he would be happy to go out with them with his sonar, but the offer was turned down.

Undeterred, Phil and the team made the journey again the following weekend. This time they did dive, the police having indicated that there was no longer any reason to stop them.

They carried out arc line searches from the shore, in an area that a dog-search team had indicated, but found nothing.

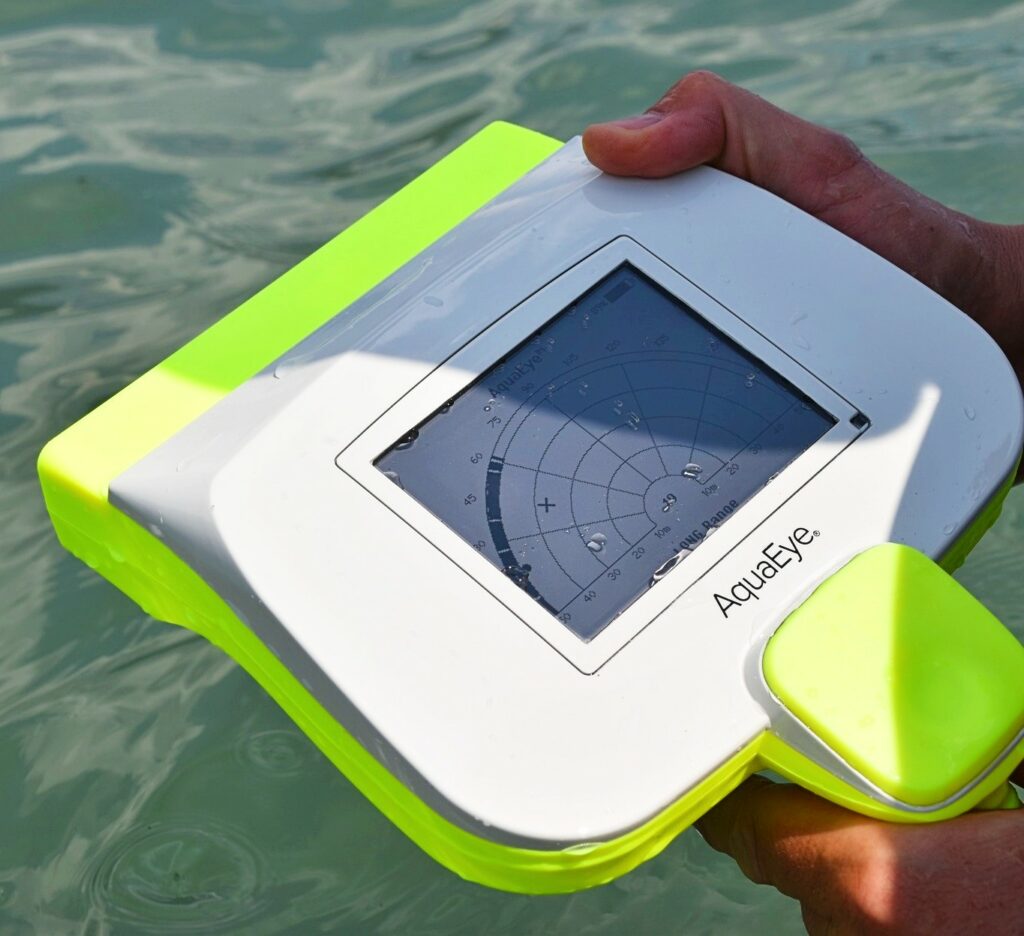

The dog searchers had been using a VodaSafe AquaEye handheld sonar unit, as widely used by North American SAR teams, and the BTS divers were interested to try it out. The next day further searches were stymied because the lake had frozen over.

The police spent another fruitless week at the site, and Beneath The Surface came up for a third time on 13 January. That’s when their own Garmin sonar finally succeeded in pinpointing the submerged boat, lying the right way up – and two hours later they had found Greig Stoddart’s body, at a depth of just over 3m.

“The minute the team came out of the water and told us they had found Greig was the biggest weight off everyone’s shoulders,” says his brother.

They will never know for sure what happened to the two anglers but “we reckon that the weather conditions had opened up the petrol outboard and just swamped it, and the back went under. They never wore lifejackets.”

New technology

The gratitude of families helped by BTS is clear when you read the comments on its Facebook page. Thomas Stoddard was so impressed by the team’s dedication and persistence that he started a crowdfunding page to raise money to get the team their own AquaEye: “I became like a dog with a bone about it,” he says.

His campaign, not only online but as a result of reaching out to the Canadian company that makes device, has now borne fruit. VodaSafe is not only about to donate a £6,000 AquaEye to Beneath The Surface but has appointed the team its UK ambassador. The handover take place at Gartmorn Dam on 16 March, with a training day to follow.

“Because we’re travelling everywhere and can show the AquaEye to police forces, it’s a good way for them to get it out there,” says Phil. “It’ll be interesting to see how it works. It’s had a lot of good reviews from the USA and Canada, where it’s quite widely used in fire and rescue.

“If it works how it’s supposed to, it takes a lot of time off traditional sonar-scanning and possible human error in reading the sonar, because it’ll scan out 50m on a 180° radius and detect any kind of objects in the water. It uses AI to figure out what is a potential person.

“If there’s anything it thinks is a possible and needs checking out, it’ll give us a zero. If it thinks it’s a person it’ll give an X, so that we can go out to check straight away.

“VodaSafe want it to be not just a recovery but a rescue tool, with as many out there as possible for use by people like lifeguards. If they’re readily available and can be used quickly it could be a lifesaving tool, which is what it was primarily designed for.”

Donations have now also equipped the divers with four full-face masks with communications systems plus a surface comms unit, allowing them to stay warmer and safer from contaminants, while reducing the risk of losing a regulator mouthpiece.

They can now keep in touch with each other under water while also receiving directions and instructions from the surface.

In late 2023 the team also managed to secure through donations a Gladius mini underwater camera drone. “It cost £1,000 but it can go down to 100m, so it’s safer than putting a diver in. We haven’t used it much yet because we’ve been working quite shallow and in dark water, when it’s often easier just to put a diver in to identify objects.”

Talking to the police

In February Phil and the team were back in Scotland 50 miles from Gartmorn Dam to conduct sonar searches of Musselburgh Lagoons at the request of the family of Daniel Fraser.

The 35-year-old Edinburgh man had gone missing in freezing conditions on 7 January. The divers found him, unusually in clear water, and informed Police Scotland so that it could recover the body.

“It’s getting to the point now, especially in Scotland, where the police do speak to us,” insists Phil. “The families contact us and the police do tend to get in touch with me. Although they can’t task us for liability reasons, they don’t restrict us from going in, and they’re quite co-operative with us.

“As we’re voluntary they can say: well, we can’t stop you going in. Sometimes they even say: this is the kind of information we can give you.

“With Daniel Fraser the chief inspector rang me and I explained our protocols. If we do find something, we do not disturb or touch it, but if we locate it on our sonar we do dive to identify it, and if it’s not too public an area we’ll mark the location with a buoy.

“If it’s a busy area, we’ll try not to attract attention. As soon as we’ve identified, we get out of the water and call the police and they come in and do their job.

“Making recoveries has only happened once or twice, under police supervision, and it’s usually if the person has been missing for quite a while and there’s not going to be much chance of evidence.”

BTS has yet to turn down any reasonable request for help. “It might take us a few weeks to respond but we try not to say no to people – because they’re people in need, aren’t they?”

“If we responded to everything we get tagged into we’d be all over the place, so we do need the direct family to ask us. They can give us the necessary information, which is always better.”

The requests seem to be coming mostly from Scotland at present, though the team has been to Wales and Yorkshire recently. “Three-hour journeys are not too bad, but we’ve been up to Aberdeen and Inverness, which are seven-hour journeys for us, and that is a long way,” says Phil.

“I’ve managed to give the lads one weekend off but I’m the one that operates the sonar and I’ve not had a day off since we headed off to Alloa on New Year’s Day!”

Being self-employed does make it easier to get away, he says. He isn’t in a relationship at the moment, either, so it’s only his dog he has to think about when travelling.

Some of the others in the Beneath The Surface crew have families and young children, so it comes down to four fairly permanent divers and two or three others who help out whenever they can.

Calling for diving recruits

Would Phil welcome further volunteers? “Definitely! We are looking for divers to possibly join the team, but we’ll want people to be properly trained before we put them into areas where they could see something, and ease them in.

“We need them to be experienced and comfortable in the water, and to be at minimum PADI Rescue Diver-qualified or the equivalent.”

Beneath The Surface has worked with dive-club members before now. “In Aberdeen we were looking for someone who had been missing for a year, so the remains were going to be skeletal, or clothing, so we’re a bit more comfortable with volunteers going in to help.

“But Greig in Alloa had been missing three weeks, Daniel in Musselburgh five weeks and Dane in Dumfries [Dane Mcgill, found on 28 January] had been missing five months, so we wouldn’t put someone inexperienced in to look in cases like that.”

“For me, the most difficult part of all this is telling families that I can’t find someone, rather than actually finding them. But it is tough obviously when we do find them, so we work with counsellors, and every time we find somebody we go and have a check-up.

“We do look after each other, make sure that people have regular breaks and everyone’s OK, because it can hit people differently at different times.”

Phil is also considering the possibility of launching a second team. “A couple of the other guys are getting good on the sonar, so it might be that we could have a Scotland- and an England-based team, and could cover two missing-person searches in one weekend, because it’s getting so busy.

“We also work with water-safety campaigners, because we’d much rather stop people going missing than having to find them.”

Presumably all thoughts of recreational diving have gone out the window? “I think I got one weekend in last year when I went up to Oban and had a bit of loch diving. I wasn’t used to being able to see what I was doing!

“We’ve had nearly four years of struggles, but we are starting to become a bit more recognised. The police will never be able to task us, but I prefer it for the families to get in touch and to be able to work with them, help them and have the freedom that offers.”

Anyone interested in joining Beneath The Surface should contact the team via their Facebook page, while donations can be made directly or through Thomas Stoddart’s appeal.

Also on Divernet: Private dive-team joins Bulley river search, Reeds not our remit, says Bulley dive volunteer, Divers find teenager’s body police had missed, Divers solve two more cold-case mysteries, Body-recovery divers crack 20th cold case

Back in the 60’s before the police had their own diving teams, they often used to ask local clubs to do search and recovery work. This was mainly dumped cars to see if there was anyone in them but occasionally body searches. The most fun was when the air/sea rescue helicopter asked us to investigate an upturned yacht when we were on a coastal dive trip. Jumped from the chopper and picked up by the lifeboat.

Then elf ‘n safety appeared on the scene and that was the end of that.