UK DIVER

NUDI GB

When you get your eye in you realise that colourful sea-slugs are not confined to the tropics – south-eastern Scotland, for example, can also be a happy hunting-ground for macro enthusiasts. RICHARD ASPINALL drops into the Scottish Nudibranch Festival

Flabellina pedata, the violet sea-slug.

WHAT AN AMAZING SITE! ‘Why did you bother with that one? It’s just seaweed and nothing to see!’

I sat back on the bench and released my BC straps, eager to have a look at the back of my camera to see if I’d captured anything of value.

In and among the usual out-of-focus images in the viewfinder, there were a few that made me happy. Jim Anderson had been right – this was one of the best nudibranch sites in Scotland.

We had left Eyemouth that morning, past the grey seals that spend their days posing for the tourists, and out onto the wonderfully calm sea.

We had headed north, up the coast to St Abb’s Head, that massive bulwark of rock that, as it falls away into the North Sea, becomes a complicated series of pinnacles and gullies.

As I was deleting images, a few more divers were returning. “Did you see how many Acanthodoris pilosa there were?” asked one. Within minutes of taking off their gear, the experts were comparing notes, and I was lost.

I’d have been disappointed if it had been any other way. We were halfway through a series of dives as part of the Scottish Nudibranch Festival, and I would be learning a great deal.

While I was at the happy-to-see-a-colourful-one stage, I was glad there were folk around who could tell me exactly what it was that I was photographing.

I’m a long way from being a nudibranch obsessive, but I can see why they are such a source of interest.

Appeared in DIVER August 2017

NUDIBRANCHS ARE AMONG the most colourful animals in the oceans. There is nothing quite like them, apart from flatworms perhaps, which confuse many of us eager-to-learn nudi newbies.

Maybe it’s their rhinophores, the sensory organs at the “head end” that lend them a cuteness factor, as well as their slow-moving, easy-to-photograph nature. Maybe it’s simply that they are so different to animals on land, reminding us of just how remarkable the underwater world is compared to our mundane lives above the surface.

I’m not sure, but I can entirely understand how, with a macro lens fitted to a camera, a dive that some might find dull (not a hint of a wreck, and only to 10m) can become special.

For me, there is something magical about my torch-light falling across a beautifully coloured gem amid the murk and cold of typical UK dive-sites.

On the face of it, the waters off Scotland’s south-east coast might not be the first place you’d think of to host a nudibranch festival. Tropical destinations come more easily to mind, Anilao and Lembeh being just two.

You’d be wrong, however, because UK seas teem with life and with nudibranchs. You just might not have noticed them.

Over a coffee and some home-baked cake, we enjoyed the summer sun and the almost flat-calm seas. I have done only a handful of dive-trips in this part of the world, and each time I’ve found myself thinking back to conversations with folk on liveaboards who swore that they wouldn’t dive “back home”.

A small pod of dolphins swam past, heading south, and the skies were full of seabirds: fulmars, guillemots and kittiwakes. So much life. Admittedly,a summer storm can ruin your plans, but when the conditions are good this is world-class diving on the doorstep.

We were diving from Marine Quest’s two boats, Silver Sea and Jacob George, and the team was treating us exceptionally well.

A history of fishing locally and salvage-diving (in the days of hand-cranked surface-air supplies and brass hats) suited the family firm’s shift to the dive industry.

OUR SURFACE INTERVAL was over, and Jim gave us a quick briefing on the best way to explore the wall and swim-throughs. As we descended, my computer registered 13°C and, as I added a little gas to my drysuit, I could see for at least 15m! This was excellent visibility.

Around us, the rocks that had tumbled from the cliffs above were capped with luxuriant growths of seaweed – from fine fronds to huge growths of kelp, each massive, leaf-like blade anchored to the rock by a thick stem and sturdy holdfast.

In this underwater forest crabs scuttled and, on the kelp itself, cowries and blue-rayed limpets grazed.

I could see nudibranchs as well. In fact there were hundreds of them. I was straining a little to see the really small ones, not many millimetres long.

Taking a few photographs and viewing them on the camera’s screen revealed them to be the common Polycera quadrilineata, an ideal beginner’s nudibranch and one I had seen before. They’re common and attractive, with yellow detailing on their gills and rhinophores. Four yellow stripes on the body explain their scientific name.

I wondered how often I had passed these little characters by on previous dives? How many times had I ignored the seaweed-rich shallows to get to the depths, ignoring entirely this leafy world?

Among the kelp holdfasts, the seaweeds turned from green to a rich burgundy under my camera’s spotting light and there, reflecting pure white, was a large nudibranch with a definite “fluffy” appearance. This was Acanthodoris pilosa (I’d learn later), also going by the common name of hairy spiny doris.

You can understand why scientific names are preferred by the experts. The large rhinophores they use to “smell” the world around them, give a fluffy-bunny appearance.

Dropping deeper and exploring the sides of the boulders which, in some cases, form swim-throughs metres high, brought us to another seascape entirely.

The rocks were covered with pure white growths of deadmen’s fingers and large patches of colourful anemones, rivalling anything from the tropics for colour and sheer numbers.

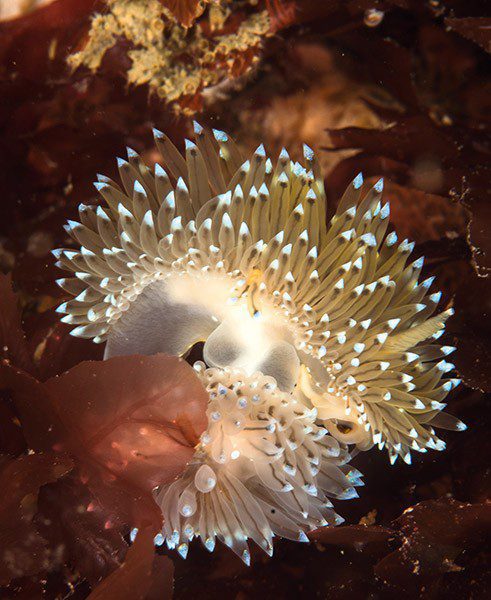

I caught a glimpse of something bright, and made out a nudibranch with the apt name of crystal tips. These are common and easily seen nudibranchs that appear to glow under torch-light.

The projections on their bodies, which serve as gills as well as containing thin threads of digestive tract, are tipped with bright white and blue.

I WAS DOING WELL at spotting the larger nudibranchs, but there was far more to come. Heading back to port on the boat, I got chatting to Jim Anderson, the festival’s organiser and lead author (with Bernard Picton) of the ebook Scottish Nudibranchs.

Jim seems reluctant to be called an expert, though he knows more about the 107 species of nudibranch and other sea-slugs so far identified around the Scottish coast than anyone I have ever met.

I could recognise around five species, and their scientific names were slowly sinking into my grey matter, but I suspect that I was the least knowledgeable person on the boat.

Jim was introduced to nudibranchs in the Seychelles in 1987, by a divemaster who was compiling a list of local species and using guests to help find specimens.

“This captured my imagination,” he told me. “There were so many species of an animal that hitherto I’d had no idea existed, and that were so colourful.”

Jim’s ebook is, he says, currently the only guide to UK nudibranchs available. A Field Guide to the Nudibranchs of the British Isles by Picton and Morrow is now out of print, though perhaps it will return in digital format so that it can be updated as our knowledge increases.

This is where divers can assist. Bodies such as Seasearch help divers to record their marine-life sightings and recordings, and records are then added to national databases of species’ distribution.

Looking at the maps for many marine species, including nudibranchs, will show apparent hotspots. This may simply be a reflection of the number of dives being made in particular places, however.

Whole stretches of coastline could be amazing habitats for nudibranchs and other species, and it’s just that nobody has recorded any yet.

The following day was another scorcher and, as we left the harbour, the ice-cream sellers were rubbing their hands with glee. Heading north once more, we explored some wonderfully named sites: Conger Reef, Craig and, our final destination, Skelly Hole. I think the best had been saved for last.

I was determined to photograph some of the smaller nudibranchs. I’d done OK with the larger specimens but was aware that some fellow-divers were finding tiny ones that, for those with good eyesight, are as pretty as their larger cousins.

“This might be my chance,” I thought, as Jim manoeuvred the boat carefully between the long sections of rock that ran out seawards. Not a site to be dived with swell, I imagine, as the local geology meant a narrow entrance to a sheltered spot, surrounded by tall cliffs hosting thousands of noisy seabirds.

As we descended to around the 15m mark, the seabed of rounded pebbles gave way to seaweed-covered rocks. A small octopus seemed eager to avoid me.

I was puzzled for a moment by the rounded rocks that all seemed to be the same size, before realising that these were the empty shells of guillemot eggs from the colonies above.

Perhaps it was the fertiliser from above, but the seaweed here seemed even more luxuriant, like some sort of a prehistoric forest. The light and clarity of the water was excellent, and without a current I could once again focus on the kelp.

Straining my aged eyes, I could make out something that might have been a nudibranch. I fired off plenty of shots and there it was, a creature 4 or 5mm long, feeding on the hydroids that grew on the kelp fronds. It was properly visible to me only as I enlarged its image on my LCD screen. I was going to need some better contact lenses.

CHUCKLING TO MYSELF and aware that there were far more nudibranchs around me than I had ever imagined, my buddy and I headed a little further out.

I could see her flashing her torch at something and, as I finned over and strained my eyes once more, there was a streak of violet pink; I had a Flabellina pedata to shoot.

Then, not many centimetres away, a tiny brown blob revealed itself to be a gorgeous little creature with tiny blue spots on its flanks. Aegires punctilucens is one of those names that means nothing until you learn, as I did, that punctilucens means “spotted with lights”, or something approximating that translation.

Adding two more species to my list was a great way to finish the dive. We had reached about 50 minutes, and it was getting a little chilly. I had more than 100 bar left in my 15-litre cylinder and a memory card with around 20 nudis on it.

My buddy was also happy to return to the surface, despite our remaining gas, so I sent up my DSMB.

As I looked up, I could see something in the water – something flew past.

There were scores of guillemots, doing passable penguin impressions as they “flew” under water all round us. I have enjoyed safety stops with oceanic whitetips and with dolphins, but never with birds. It was the perfect end to a great weekend.

- The Scottish Nudibranch Festival 2018 is expected to run in the middle of June, with exact dates to be set. Check Marine Quest’s website, marinequest.co.uk