We always look forward to hearing about the latest South-east Asian adventures of technical diver TIM LAWRENCE, and a recent expedition took him to the Philippines for some interesting work-up dives prior to exploring the deep-lying wreck of a Japanese ferry. But did this vessel ‘with the heart of a cruise ship’ suffer the curse of one too many name-changes?

Mariners have always been a superstitious lot. Tales of the sea get interwoven with myths to create classic stories, like those of the Mary Celeste or the Flying Dutchman.

These tales create dos and don’ts that follow mariners around like the fog on a becalmed sea. Whistling on deck? Changing a ship’s name? Such transgressions are enough to elicit notes of caution from old hands. Ignoring them could risk bringing about a vessel’s doom.

The Sunflower 2 entered service in 1974, intended for the Osaka-to-Kagoshima ferry run. Fitted with cruise-ship amenities, she also got ultra-modern fin stabilisers to help with pitch and roll in heavy seas, and adjustable water-ballast tanks to offset heavy loads, a luxury in the ‘70s.

The Sunflower 2 was at the forefront of ship design and served the people of Japan for 16 years, before rising petrol prices forced her sale back to the original shipbuilder.

The builder retrofitted and renamed the ship Sunflower Satsuma, hoping to maintain the Osaka service. However, she lasted only three more years before being sold again in 1993 to Sulpico Lines, a Philippines ferry company in need of a makeover.

Sulpico fitted a new car ramp to the starboard side, added extra cabins and changed the identity again. The newly named Princess Of The Orient was put into service on the lucrative Manila-to-Cebu passage.

The Princess was a ferry with the heart of a cruise ship. She had beautiful lines and facilities, and was enormous at 13,935 tonnes and 195m long. She quickly became the failing company’s new flagship. The 430 nautical-mile passage to Cebu took 23 hours.

The Sulpico Line needed good press. Incidents that included a catastrophic collision with the Donner Paz had placed the company squarely in the firing line, so a veteran, Captain Esrum Mahilum, was tasked with improving the line’s image.

18 September, 1998

Captain Mahilum stood on the deck of his command, carefully weighing up the odds. The company was loyal, but his relationship with it was frayed. A series of unfortunate mishaps had pushed him to the edge of his employment.

His ship had only recently collided with the bottom of Manila North Harbour and, in a separate event, had sideswiped a container ship. The most recent calamity had been a fire at the dockside, knocking out the port fin stabilisers and forcing repairs in Singapore that, despite being costly, had left the stabilisers still inoperable. He quietly hoped that lousy luck came only in threes.

But then a typhoon had sprung out of nowhere to the west of Manila Bay, and a warning was issued to all boats. Delaying the Princess’s departure allowed the worst of the storm to pass. With many cancellations, the passenger list and cargo would be much smaller than usual.

The captain ordered his water-ballast tanks filled to compensate. Flooding them would take hours, but reducing the ship’s freeboard would improve her stability. Without working fin stabilisers, she would still pitch heavily in big seas, so Captain Mahilum could only hope that the passengers would be comfortable.

The satellite images were positive. Looking out from his bridge. a 3° list to port was visible to his trained eye, a nasty keepsake from the dock fire. “Damn those fin stabilisers!” he muttered. His command felt different since the fire, almost as if the Princess Of The Orient was a different ship.

At 10pm she left her dock. The ballast tanks were filling, and there was still a full 90 minutes before she would be exposed to the typhoon’s tail.

But the crew had failed to secure the reduced cargo properly, doing no more than placing chocks on the truck wheels to prevent movement. Falsely reassured by the pitch in heavy seas on previous voyages, they were oblivious to the loss of the ship’s stabilisers.

The sea had its own ideas. Typhoon Vicky changed track and headed north-east to make land close to Dagupan. The storm was also transforming into a rare explosive deepening, pushing the swell up to 8m. The storm-centre shifted north, with the Princess heading directly towards its teeth.

Ninety minutes after leaving port, Captain Mahilum watched his ship battle the swell. Surprised by the storm’s intensity, he ordered a turn to port earlier than usual and slowed to 14 knots, intending to run for Fortune Island and shelter in its lee.

Still a little light and without the fin stabilisers, the ship’s ballast pumps struggled to get the water into place.

She pitched heavily, the full force of the waves hitting the starboard side. The cargo that had not been lashed down shifted to port, quickly increasing the list to 20°, and the captain attempted a series of manoeuvres to reduce the waves’ impact, ordering water to flood into the starboard ballast tanks.

The sea continued to pound the ship, however, and only two hours out from Manila the list had increased to 45°. With every wave, the once-proud ship was being pushed closer to Davy Jones’ Locker.

Captain Mahilum was last seen helping passengers into the lifeboats and, in true maritime tradition, went down with his ship.

Was he to blame, or was he a victim of bad luck? No fewer than 150 souls drowned, leaving the others to endure a 12-hour struggle for survival until local fishermen were able to brave the conditions to come to their aid. Captain Mahilum, no longer able to fight his corner, became the scapegoat.

22 March, 2024

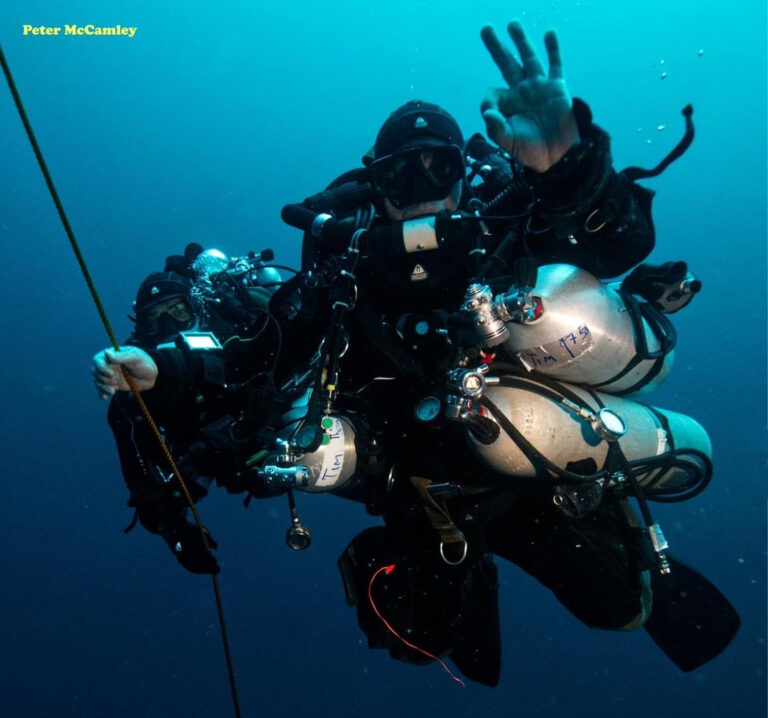

Sam Beane and I sit in the hotel lobby in Subic Bay, waiting for Peter McCamley, an internationally respected and, as it turns out, highly likeable Irish advanced technical wreck explorer with the Blarney Stone firmly in his back-pocket.

Pete bounces into the room and promptly hugs Sam and me – an unexpectedly warm welcome. We jump into his rental car and head for a meeting with Mike, aka Captain Sparrow, and his crew.

On the way we get an insight into Pete’s unusual driving technique, one that hasn’t gone unnoticed by the local constabulary. His generosity is also on display – when stopped and questioned, he immediately contributes to the local kids’ orphanage!

When we finally leave port, we’re disappointed not to see a representative from the orphanage there to see us off. The police must have been sad to see us go.

The Caribbean Tigress is a tech diver’s dream. Mike, an equally respected wreck explorer from Australia, is passionate about the sea, and it shows in his ship.

Covid delays have reduced the number of divers joining our group to three, so we get a cabin each, with our youngest member Sam getting the cheap seats next to the forecastle.

IJN Kyo Maru

We load quickly and head out for our first work-up dive on the WW2 submarine-chaser IJN Kyo Maru, lost off Sampaloc Point in Subic Bay in a US air attack on 2 March, 1942. The water is a warm 27°C, and a diurnal tide halves the current by pushing the movement over 24 hours.

The visibility is up to 20m on the 70m-deep bottom, a luxury! At 45m I can already make out half of the wreck. A 5in artillery piece lies upturned off the port side, its wheel unmistakable, and poking up through debris alongside it is a helm minus the wheel.

Although pretty broken, parts of this ship are easily identifiable even to the untrained eye. This had been a beautiful whaler before being requisitioned by the Japanese Navy.

Proximity to shore means we can shelter each night in one of the picturesque bays along this coastline. We head out to another wreck at the same depth the following day.

Coral Island

The 1,459 tonne, 73m cargo vessel Coral Island was built in Japan in 1965 and used in various ways, including transporting medical supplies to surrounding islands.

An engine-room fire while the ship was heading from Batangas to Manila caused an explosion that killed 21 of the 95 people on board. The ship had clung to the surface for three days before finally submitting to the grasp of the deep on 29 July, 1982.

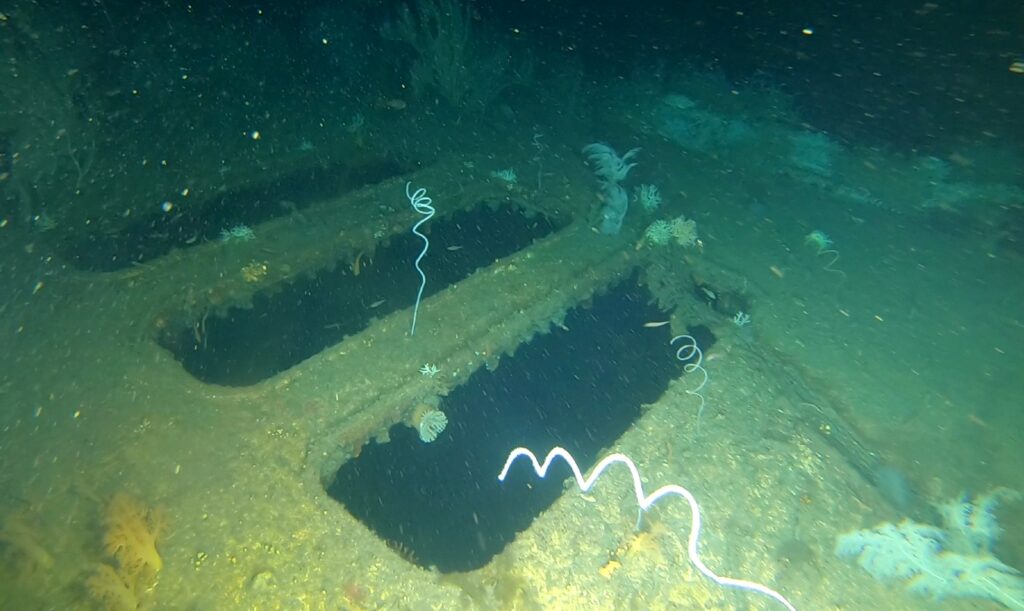

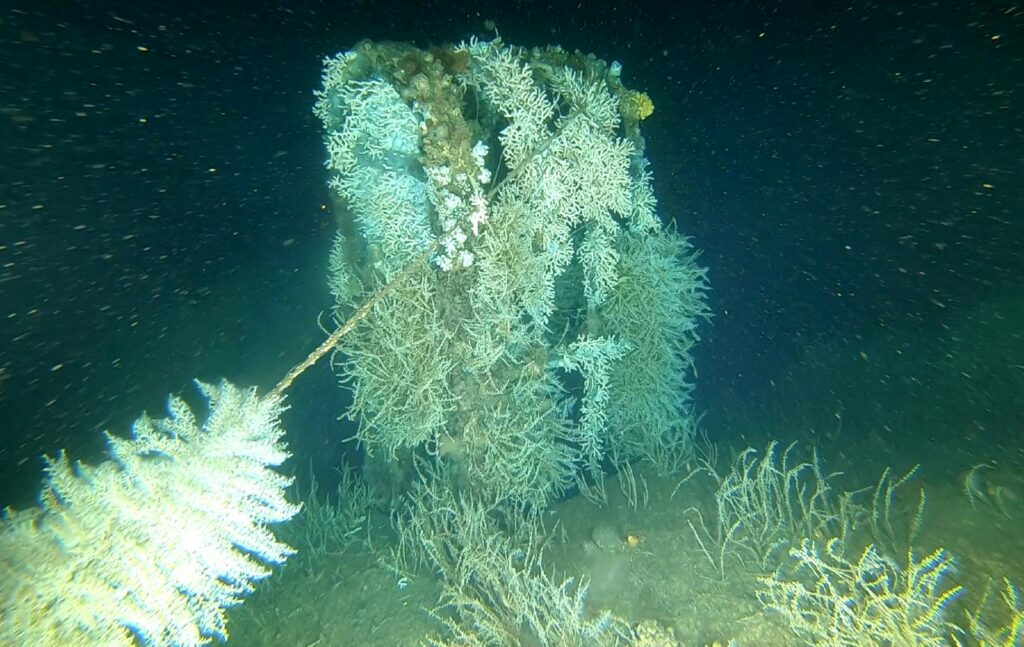

The wreck lies at a maximum depth of 68m. Mike places the shot just forward of the starboard bow, line looping across the mast that reaches towards the light. Following the mast into the deck, a vast, dark hold invites us to enter. I run a distance-line into it, looking for any signs of the ship’s last moments.

Moving between decks, we pause to look around. The weight of the superstructure has caused the deck to drop in the middle like the inverted bow of an archer – pointing out the trap, Sam and I turn, carefully retracing our path to the mast and our exit.

This epic shipwreck holds us all in wonder and, as soon as we have cleaned our gear, we make a unanimous decision to go back.

Early the next day Mike places the shot, this time at the stern. The fire must have weakened the keel aft of the bridge. The hull is twisted and broken, giving us an excellent opportunity to swim through the aft quarters.

My mind harks back to that more leisurely age of travel in which ships would carry cargo and passengers in comfort around the thousands of islands that make up the Philippines archipelago.

Keen to get an extended surface interval we leave this wreck, bristling with oddities and reminders of yesteryear.

At 3pm we jump in once again, planning only a short bottom time. The current has picked up considerably and the shot’s weight cannot hold against the drag from three heavily laden divers.

Our slow descent succeeds in pulling the weight off the mark, rewarding us with only the blue void tempting us to continue at 80m. We run a line out, but turn early when the speed of the dragging shot becomes evident from the trail in the silt.

The prime target

Time constraints force us to move on to our expedition’s primary target, so our minds collectively shift to the next dive. We save a substantial gas bill by upcycling Mike’s old bail-outs while ticking all the boxes with some creative blending, and head for the Princess Of The Orient.

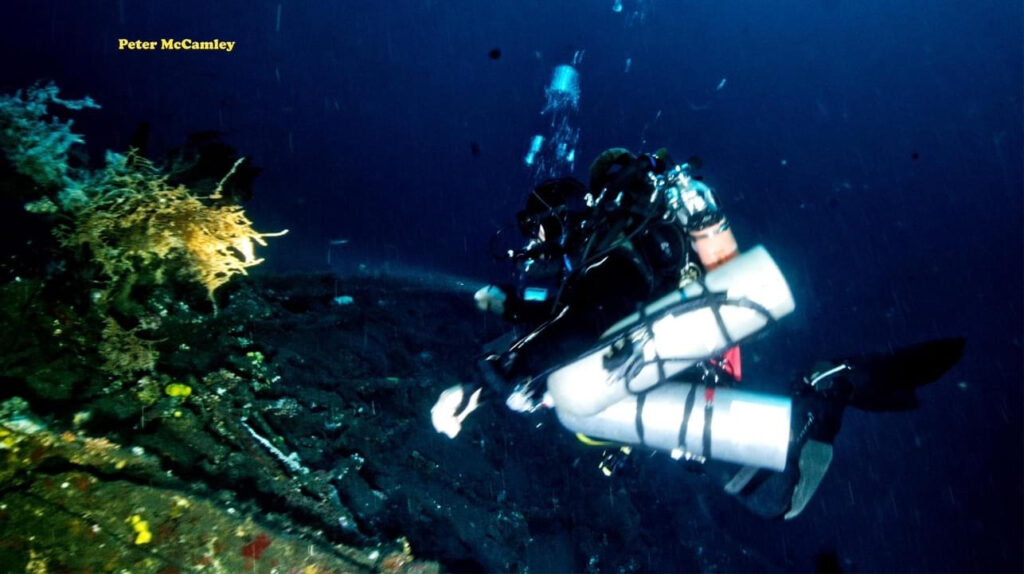

Mike places a large concrete block on the wreck, intending to use the line to station overnight. The wreck lies on its port side, with the top of the midships at 108m and the sand at 130m.

We sit on the dive-deck, waiting for the go-ahead, my mind visualising the dive. I hope the shot will be around the bridge, or at least close to the fin stabiliser on the starboard side, because I want to know if the fire caused both to be extended or retracted. It’s a small detail, but it might have affected the ship’s stability.

Shot-placement is critical to the effectiveness of a dive on a vessel of this size at such depths. Scooters help to cover ground, but there is only so much you can accomplish on a dive at 100m+.

A cold shiver runs through me in the 14° water, so I’m happy to have the drysuit, while also surprised by how little ambient light there is.

The shot has passed through the central doorway, so we enter the ship’s starboard side opposite to where the passengers would have entered it, seeing the ladders still extended and in place.

We pull ourselves along, trying to gauge our exact position, struck by the enormity of this vessel and the extreme force that would have been required to send her to the depths.

“It’s like landing in the middle of a football field,” recalls Peter later. “Fortunately the shot was spot on and close to the edge of the deck, which allowed us to drop down and view the deck.

“I recall seeing a ladder gantry and think it might have been the boarding gantry. The other thing that blew my mind was the condition of the wreck and how intact it was, with the paintwork on the side and deck looking like it was painted yesterday.”

Our 20-minute bottom time passes quickly, and Peter’s strobe guides us back to the exit, where we begin our ascent and three-hour decompression.

We dive again the next day, this time with a bit of a run and, after checking the shot for wear, our bottom time allows us only to look at the empty lifeboat-davits. I wonder which lifeboat station the captain was last on. This second dive serves only to show us how much of this big ship remains to explore.

We leave the Princess. The enormity of the wreckage and our time constraints have left us only with further unanswered questions, but they will have to wait for the next team of rebreather explorers.

Corregidor

The day before, Mike had produced two unexplored marks around Corregidor, a small island at the entrance of Manila Harbour used as a fort and, as always, the temptation to explore uncharted waters pulls us away.

That afternoon, we ride into Batangas on a bike-taxi to enjoy the local culture. I hope drinking the local whisky won’t affect my eyesight. We perform a hit-and-run through town that would have made Bonnie and Clyde proud.

A sounder survey of the two marks shows a 4m rise of about 40m in length, 56m deep. To solve the problem of drag, Mike sets a small Danforth anchor fitted with a gate-clip on the business end and enough weight to hold the shaft down. We set out to investigate the site.

Entering the water, we drift into the line. Water movement and sediment have reduced visibility in this channel to 50cm at best. I can make out depressions and voids in the silt and we run a line out, but soon realise that, whatever this is, it is sub-bottom, so end the dive.

I hope to have more luck the following day, but the soft silt at the entrance to the vast bay once again stymies our exploration.

Running a line out, we’re suddenly startled to feel, as well as hear, an explosion reverberating through our bodies! Turning quickly, recovering the line now seems to take an eternity, and then a second explosion invades our space, hastening our exit.

I signal our first stop to Sam, and we spend the next 40 minutes hoping that, if there are any more explosions, they won’t be any closer. This fish-bombing gives us a sober reminder of the challenges faced by divers willing to travel off the beaten track to explore this area of the sea that has proved, as ever, reluctant to give up her secrets.

Thanks to Snake for his valuable research into shipwrecks in the area; Peter McCamley for organising the expedition; Mike (Captain Sparrow) for his superior captain skills and unwavering enthusiasm; and Sam Beane for being my buddy.

TIM LAWRENCE owns Davy Jones’ Locker (DJL) on Koh Tao in the Gulf of Thailand, helping divers take their skills beyond recreational scuba diving. He also runs the SEA Explorers Club.

A renowned technical wreck and cave explorer, and a member of the Explorers Club New York, he is a PADI / DSAT Technical Instructor Trainer.

Also by Tim Lawrence on Divernet: Destroyer wreck dive-quest in Brunei, Wreck-dive obsession: Brothers in arms, Decoding Maritime Mysteries: A Diving Expedition in Thailand, The Ship’s Bell, ’I’d been wreck-hunting when the dive-boat sank’, Burma Maru