A US submarine is lost during the Pacific war, depth-charged by a renowned Japanese convoy escort vessel. Tech divers find that sub 19 years later, but TIM LAWRENCE remains intrigued by the escort, IJN Hatsutaka, and by a colourful account of its vengeance sinking by another US sub commander. Prepare to be taken back to 1945 – and then forward to a remarkable shipwreck discovery in Malaysian waters

Captain JW Travis takes comfort in the melodic purr produced by his Pratt & Whitney engines – unlike his look-outs, who are trying to resist the temptation to sleep as the hypnotic hum seduces their senses.

Also read: Dive trip temptations: Philippines & Malaysia

Their PB4Y-1 Liberator aircraft provides few comforts, and overcoming fatigue is critical on long-range scouting missions. They are close to turning for home, but for now Luzon in the Philippines remains more than 10 hours away. A flask of coffee helps to jog the look-outs back into the moment.

A foam trail zig-zags its way across the window. It’s a small convoy of surface ships – a tanker, an auxiliary and their escort, easily visible against the blue backdrop.

2 May, 1945

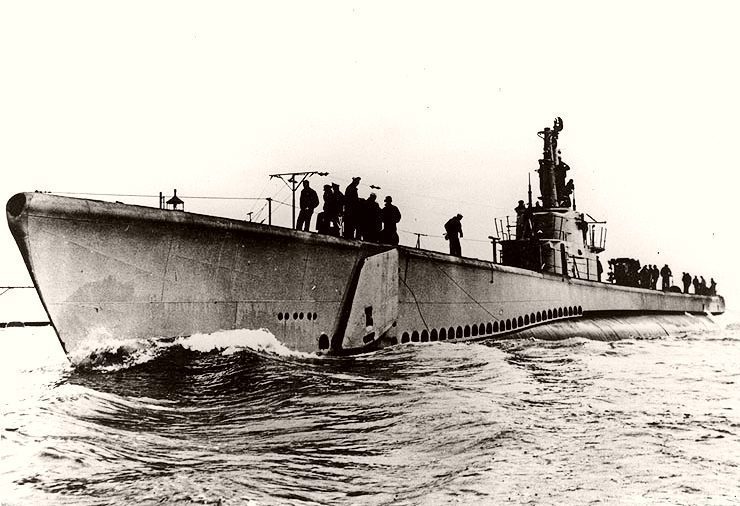

1500 Captain Travis radios a contact report. Ten thousand feet below, Cdr Jarvis on the submarine USS Baya receives it and parallels the coast to intercept. Twenty knots at the surface – Balao-class subs are fast.

2155 USS Baya makes radar contact. Unfortunately the full moon is rising, so there will be little from cover of darkness. Cdr Jarvis rolls the dice.

2210 Cdr Jarvis sends a contact report to Cdr Latta aboard another sub, USS Lagarto. Latta is a submarine service veteran at 36, with nine successful patrols behind him. This patrol is only his second aboard Lagarto but the charismatic commander is already gaining a reputation. The wreckage of the Japanese submarine RO49 bears testament to the effectiveness of his new crew, earning them the nickname “Latta’s Lancers”.

Cdr Latta has been peering at the dismantled Harley-Davidson motorcycle stored, against regulations, in corners of his bridge. His second-in-command, Lt Mendenhall, brings him back to the present, and Lagarto changes course.

2245 Cdr Latta confirms contact and responds, reporting the convoy to be on a base course of 310°, true speed 9 knots. Both the escort vessels appear to be equipped with radar. Cdr Jarvis aboard USS Baya positions his sub starboard of the convoy, unfortunately placing the light of the moon at its back.

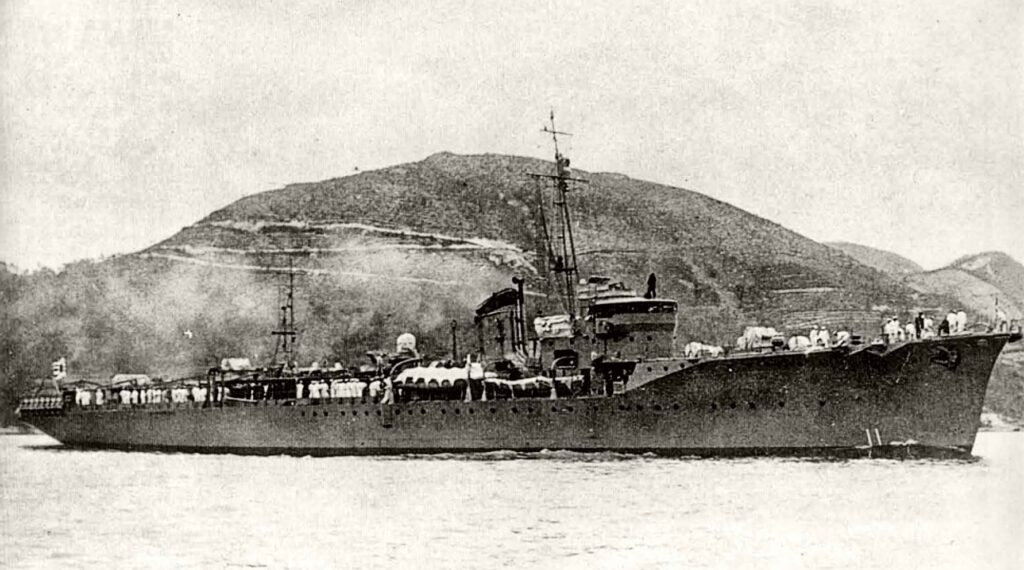

2305 On Baya, Cdr Jarvis gives the order for two torpedoes to be run out at a range of 1,500yd. Aboard the convoy escort vessel IJN Hatsutaka, 60-year-old veteran Lt-Cdr Ozaki Takashi takes the bridge. The seven months of his command have made Hatsutaka an efficient ship and earnt him a grudging reputation among US submariners. The ship was a minelayer converted for convoy escort duties by upgrading the sonar and fitting depth-charges.

Alerted by the sound of aircraft engines, Hatsutaka’s look-outs warn their captain of foam trails closing in. He turns his ship into their bearing and, narrowly, they pass along the length of his vessel. Increasing speed, Takashi charges the aggressor, opening fire with small arms and a 25mm cannon. The intense barrage passes over the top of the low-lying Baya.

2320 Both escort ships illuminate USS Baya in their searchlights. Cdr Jarvis turns the sub around, increasing speed and hoping to escape the oncoming vessels. Defiantly he fires three torpedoes towards Hatsutaka, but once more they run the length of the escort.

Again, Baya seeks to escape. Cdr Jarvis unleashes more of the Type 24 torpedoes before crash-diving, changing course as soon as the sea swamps his conning-tower – the first move in a deadly game of cat and mouse.

The margin for error is small. Everything is stopped. The men on Baya stand in silence, broken only by the sonar pings, evidence of the frantic search above. They wait for the onslaught that is sure to follow.

Some minutes pass before an eruption breaks the silence. The submarine rocks violently, and the crew force themselves to hold their nerves as the vibration sweeps through their bones. The six depth-charges 10 seconds apart push the men to breaking point.

2333 Mercifully, the sounder pings lose intensity. The escorts turn away and the crew of USS Baya breathe a sigh of relief. The contact has lasted 28 minutes.

Cdr Jarvis later reports: “It’s nothing short of a miracle that we came through so much gunfire without a scratch.”

Baya makes a rendezvous with USS Lagarto early on 3 May and the two commanders form a plan. Lagarto is to make contact at 1400, then dive on the convoy’s wake. Baya will wait 10 to 15 miles farther along the track. If there is no further contact between the two submarines, Baya will intercept the convoy at 2000.

Baya makes no further contact with Lagarto, despite numerous attempts. So Baya attacks alone, but again is driven off by the escorts and returns to Freemantle. The convoy and its escort continue unscathed.

Vengeance for Lagarto

Cdr Francis Scanlan of another Balao-class submarine, USS Hawkbill, gave the following account of the sinking of IJN Hatsutaka on the day USS Lagarto was declared overdue, on 4 May, 1945:

“[This] story begins the day following our sinking the small convoy when on the evening Fox schedule from Pearl Harbor we heard a message from COMSUBPAC announcing the loss of Lagarto in the Gulf of Siam when depth-charged by the destroyer Hatsutaka.

“The skipper of Lagarto (a sister-boat of ours built at Manitowoc) was a wonderful friend of mine named Frank Latta.

“When I received the news of his loss, I immediately went to the charts and concluded that Hatsutaka must have been escorting a convoy from Singapore to Saigon. Most likely, she would have to return to Singapore for another convoy and thus provide Hawkbill with an opportunity to avenge the loss of Lagarto.

“So we sent a message requesting permission to deviate from patrol orders long enough to take on Hatsutaka, which was approved by COMSUBPAC.

“Taking up position a mile or so off Pulo Tengol, an island located approximately at the south-eastern corner of the Gulf of Siam, we would likely intercept Hatsutaka, whichever way she returned to Singapore. I wrote in the captain’s night order book to maintain a sharp look-out and to use the emergency call-bell at the head of my bunk if we made contact of any kind.

“It was a rainy night, and we were near the Equator (on the surface charging batteries, of course). I stripped down to the buff and fell asleep on my bunk. The next noise I heard was the five buzzes on the emergency buzzer from the bridge, telling me in no uncertain terms: ‘Captain to the bridge, on the double!’

“I hit the deck running and was halfway up the ladder between the control-room and the conning-tower when I realised that, in the excitement, I had neglected to put on some clothes! Finally I arrived in the conning-tower, and was told that the target was within torpedo range, and that we had a firing set-up on the torpedo data computer (TDC), where Lou Fockele was busy twirling knobs and urging me to hurry.

“Reaching the bridge, I grabbed the target-bearing transmitter. With the bearing acknowledged by the fire-control party in the conning-tower, I gave the order to launch three torpedoes in a spread at our target, which was still standing southward down the Gulf Coast, just as we had guessed she would.

“Our stopwatch counted one minute from the torpedoes launched. On the bridge, we got rewarded with the sight of a large explosion. Lou reported that the target had ‘come to a stop’. Then she sighted us, or her radar picked us up, as we found ourselves coming under fire from several ships’ medium-calibre guns.

“We turned away and sought safety by opening the range between our victim and us and, about this time, some kind shipmate quietly reminded me that I was still quite naked!

“During the remainder of the night, our target remained stationary and we, on the surface, both awaiting dawn to assess the situation. We recognised that we were in very unfriendly waters. The Gulf of Siam averages about 15 fathoms [27m] throughout, and our keel was only 26ft [8m] from the bottom when submerged.

“Besides that problem, there lay between us and the drifting enemy (by daylight confirmed as Hatsutaka) a large US-laid minefield, which I was reluctant to enter. An enemy floatplane was circling lazily around the destroyer.

“Eventually, a sea-going tug appeared with the obvious purpose of stealing our victory from us. By this time (perhaps 0900), we were submerged, and a range with our radar-equipped periscope showed us to be out 5,000 yards from Hatsutaka.

“Our torpedoes had two options in speed, 30 knots and 45 knots, with corresponding ranges of 5,000 yards at slow speed and about 3,000 yards at high speed, as I recall. In any case, were we to fire a fish at the enemy as a last-ditch effort to avert her escape, we would have to be very lucky.

“As every man aboard Hawkbill was the best in his field, I had full confidence in our torpedo gang to give us a “hot, straight and normal” run. I ordered a forward tube to be readied for firing, the torpedo set at maximum range slow speed and, because of the minefield, zero running depth.

“With heartfelt prayer and wish for all the luck we could muster, I ordered that torpedo fired from a tube in the forward torpedo-room. With the periscope raised, I watched every foot of that baby run for five eternally long minutes as she left a trail of blue lube-oil smoke in her wake.

“I can give you my word that the sight of that fish coming inexorably at them had the crew of the Hatsutaka firing every gun they had at it, to no avail. As I watched, the luckiest torpedo in US submarine history struck the target squarely between the smokestacks and blew her into two quickly sinking pieces. Lagarto was avenged!”

Relocating IJN Hatsutaka

In 2005 a team on the Trident, a technical-diving liveaboard vessel owned and run by Jamie McCloud, located the wreckage of USS Lagarto. The diving community took notice. Intrigued, I began researching this ship’s history and, in particular, the fate of IJN Hatsutaka, its formidable foe.

Armed with the war-record report and plenty of enthusiasm, I travelled to Dugun in Malaysia and the small fishing villages along the coast there. After some nights spent in small bed & breakfasts, I happened on a fisherman willing to take us to a place that regularly left him with old metal debris in his nets.

The location was five nautical miles from the war record report and some 200 from where Lagarto had been discovered. I arranged to charter the man’s boat, and returned home to Thailand to assemble a team.

A week later, we loaded the night-boat to Chumporn. There we hired a minivan to take us and our equipment to the Malaysian border. Twenty-four hours later, after a sleepless night bouncing around in the back of a van, we arrived.

Luckily we had planned to lubricate our journey with whisky and, as good tech divers, we stuck to the plan. So crossing the border early after some last-minute lubrication for the customs official (non-alcoholic offerings) we made the short hop to Dugun.

We had loaded the fishing-boat by 11am and headed to the mark. The fishing-boat bore all the signs of a struggling industry, and I hoped that the sea would be kind!

Three hours later our group was huddled around a makeshift echo-sounder, with cable tied to a wooden pole lashed to the most robust rigid strut available. A lump soon appeared at the bottom of our screen. Surprised by the speed of events, we scrambled to prepare the shot-line, positioning it at the shallowest point of the wreckage.

We had planned for two dives, and with only 35m showing on the echo-sounder, we knew that we could make the dives long ones. Top that with 20m visibility!

Apprehensively, however, we awaited the downside, and didn’t have to wait long – it was that the current was strong enough to pull a winkle out of its shell. A hastily positioned line helped to offset some of the effort needed to overcome it. At last we entered the water, pulling ourselves slowly to the descent into Davy Jones’ locker.

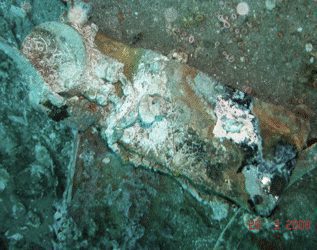

A gun-barrel came into view, defiantly pointing towards the surface, and at that moment; a hawksbill turtle swam effortlessly past, the symbolism not escaping us.

We hid behind a large piece of twisted metal plate, evidence of the intense explosion that had sent this ship to its grave. Then, after catching our breath, we began to pull ourselves towards what we imagined would be the bow area, assuming that our information was correct. Along the way we passed 25mm shell-casings strewn around gun-mounts.

Instinctively we began rummaging around, and a circular object caught my attention. Covered in bland white coral growth, a type I knew to grow on brass, I started to dig it out.

After 10 minutes I was able to free the object. Pulling myself towards the ascent-line, I quickly connected the brass loop to a lift-bag via a leash and blew it to the surface.

Quick resolution

We ended the dive flagpoling up the line. Our decompression was mercifully short on the last stop. I peered towards our find just in time to see it break free and head once more to the bottom.

Finding nautical instrumentation with a maker’s plate can help to identify a wreck, and losing it on a lift is tragic. Manny, the dive team B leader, promised a quick resolution.

Sure enough, the lift-bag reappeared only 15 minutes after he had left the surface. I jumped in, pulling myself across towards the metal object. Once on the boat, we began to clean the instrument, and 70 years of growth quickly fell away. What it revealed was a gyroscopic prism compass, complete with maker’s plate (see intro shot) – jackpot!

Finding a gyroscopic prism compass on a trawler is admittedly improbable, but on the next dive we recovered a 25mm cannon shell, leaving the other pieces that were scattered around the ship in place. And our research revealed that the first item recovered had indeed been the Hatsutaka‘s ship’s compass.

Japanese records show that the Hatsutaka had engaged with depth-charges and was presumed to have sunk an American submarine on the late evening of 3 May, 1945. On 10 August, 1944, USS Lagarto was stricken from US Navy records.

This article is in memory of the supreme sacrifice made by the 86 men of USS Lagarto, now on eternal patrol.

TIM LAWRENCE owns Davy Jones’ Locker (DJL) on Koh Tao in the Gulf of Thailand, helping divers take their skills beyond recreational scuba diving, and is affiliated with pro-level dive-school Scuba Dive Online.

He also runs the SEA Explorers Club. A renowned technical wreck and cave explorer, and a member of the Explorers Club New York, he is a PADI / DSAT Technical Instructor Trainer. (Photo: Mikko Paasi)

Also on Divernet: The Ship’s Bell, ‘I’d Been Wreck-Hunting When The Dive-Boat Sank‘