After a solid month spent under water, aquanaut Fabien Cousteau was inspired to build his own global chain of undersea habitats on a whole new scale. That was 10 years ago and his team are edging closer to completing the inaugural lab off Curaçao. STEVE WEINMAN meets the diver charged with capturing the public’s imagination for this ambitious project

Lisa Truitt was chatting to old acquaintance Fabien Cousteau at an Explorers Club meeting in New York, shortly before Covid broke. Not far away, in Times Square, the spectacular Ocean Odyssey was still drawing the crowds – Lisa had masterminded this ground-breaking immersive experience for her long-time employer National Geographic.

“Fabien, you should really think about immersive entertainment, it’s a great way to communicate with the world,” she told Cousteau.

“OK, I really want you to meet my CEO,” he replied.

Lisa and the CEO, another Lisa (Marrocchino), hit it off. “I started helping them immediately as an advisor, and became a full part of the Proteus team three years ago,” says Lisa Truitt.

Today she is bringing to bear her vast experience from the world of high-end media to her role of chief business development and creative director of Proteus Ocean Group (POG) and its much-heralded “International Space Station of the Sea”.

It had been Fabien’s grandfather Jacques who built the original three Conshelf underwater habitats in the Red Sea in the early 1960s. Since that time, more such facilities have been installed around the world than I had thought, although apart from Florida’s MarineLab it does seems to have been very much a ’60s obsession.

Most of these habitats came and went beneath the waves without leaving much trace on the public consciousness. Aquarius off Florida is the best-known surviving facility, having proved in particular its usefulness to the US space programme.

As a Cousteau, Fabien had been reared on the concept of aquanauts living and working in saturation. In 2014 he brought a team to Aquarius and they beat by one day his grandfather’s 30-day record for living under water.

They reckoned they had managed to perform three years’ worth of equivalent scientific research during their live-streamed Mission 31 adventure, and the experience prompted Fabien to concoct his own ambitious plans for an undersea lab.

“He saw how much could be accomplished both scientifically and in terms of engaging the world in the story, because they had tremendous press interest and engaged a lot of school groups through the live broadcasts,” says Lisa Truitt of Mission 31. “He thought: imagine what we could do with a better, more sophisticated system and longer stays.

“As with all great ideas, it needed time to percolate and grow, but he talked to people about it, pulled the team together and announced it in July 2020.”

This was soon after Lisa had become involved, although the first manifestation of what Cousteau hopes will become a worldwide network of modular habitats, each one four times the size of Aquarius, won’t see action before 2027.

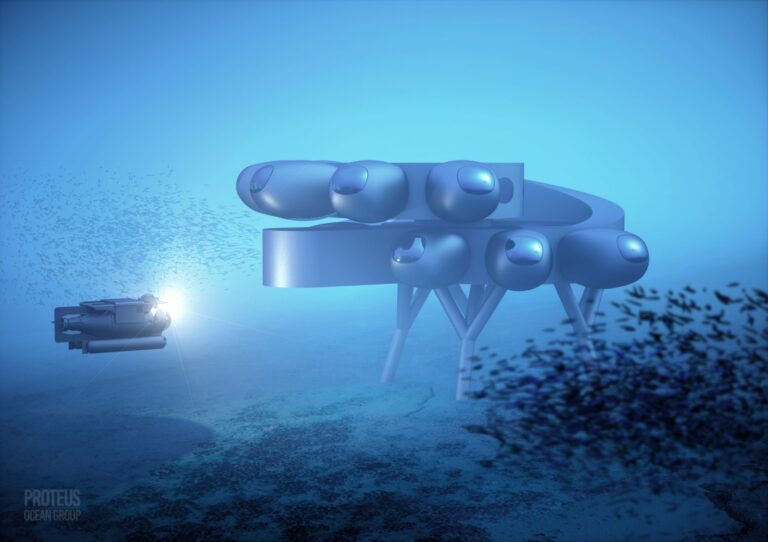

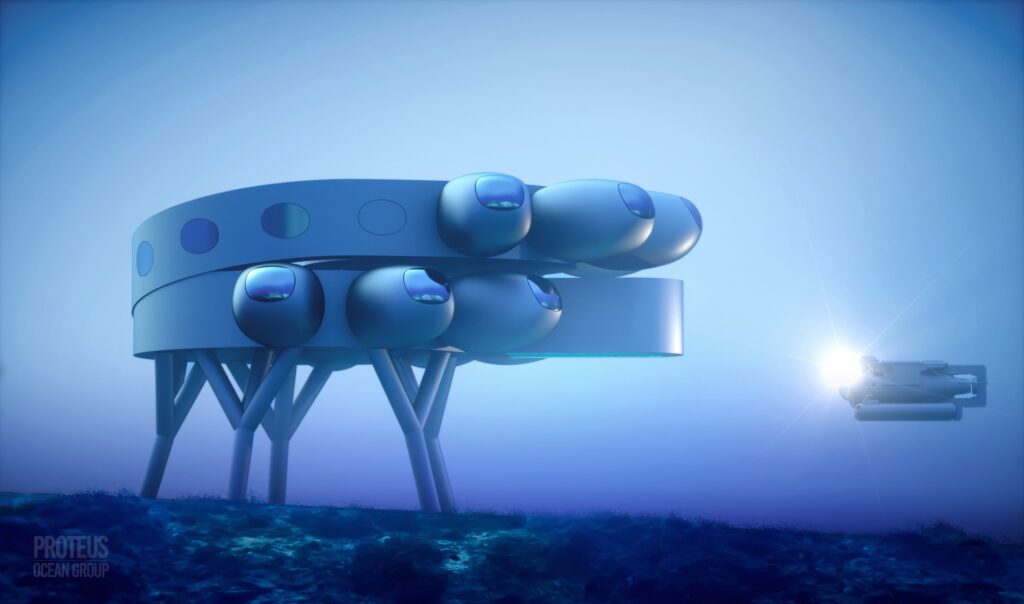

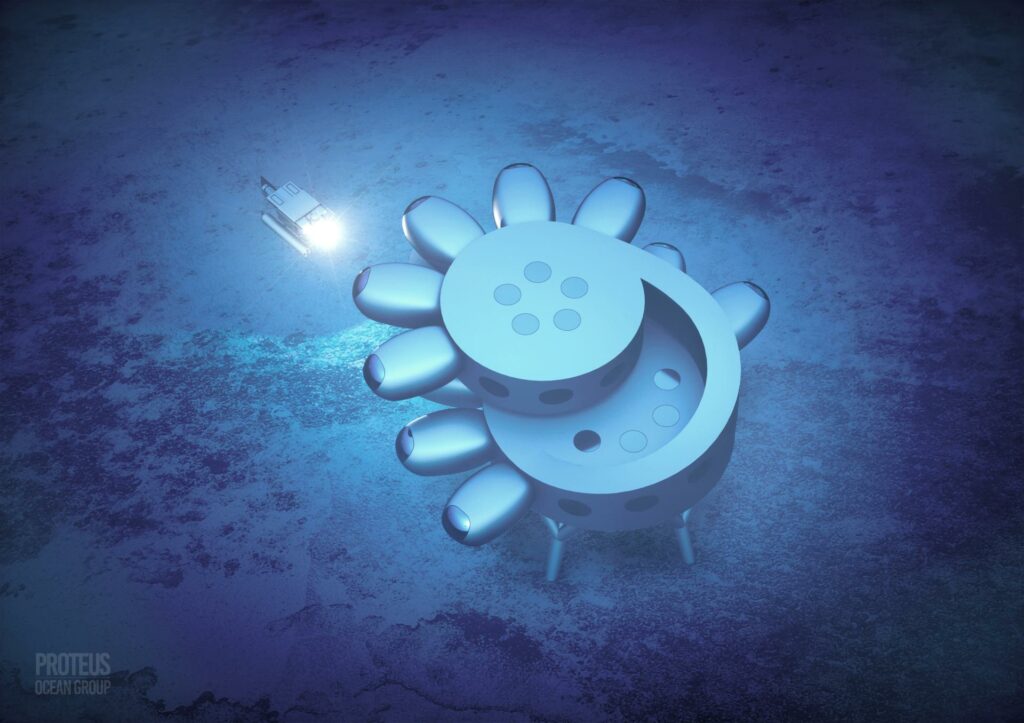

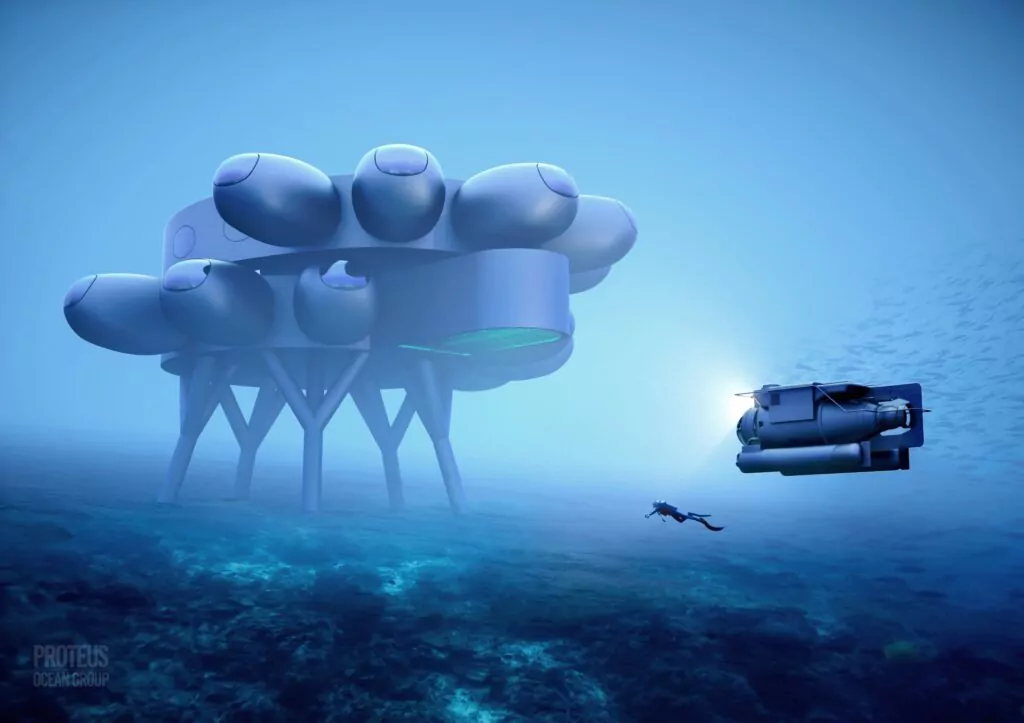

Lying 25m deep off the southern Caribbean island of Curaçao, this multi-purpose facility will have a distinctly futuristic flavour, if the original concept images are a guide, though I’m told that more up-to-date designs will be forthcoming later this year and will surpass them in terms of impact. They were too hush-hush to reveal here, sadly.

Rolex Scholarship springboard

Lisa Truitt learnt to scuba dive in cool Pacific seas off Monterey, California, and went on to become one of those envied divers who over the past 50 years have been selected as a Rolex Scholar. The prize is a dream year of paid-for dive-industry experiences around the world arranged by the society Our World-Underwater (OWU).

Her scholarship year was 1983, and while at one point working on dive-boats in the Cayman Islands she got to meet NatGeo’s star underwater photographer David Doubilet.

“So it was OWU and scuba diving that got me into my career,” she tells me. “I had been planning to go into medical school but David and his photo-editor introduced me to National Geographic – and I kinda hung on.” She would spend some three decades there.

“I did a lot of underwater stories at NatGeo, including managing the project with Jim Cameron to dive into the Marianas Trench, and got to know Sylvia Earle, Bob Ballard and a lot of the underwater greats such as Fabien.” Her own diving would take her by preference to remote locations, from beneath Arctic ice to the well-preserved 16th-century Baltic warship wreck Kronan.

From TV Lisa progressed into increasingly immersive formats with NatGeo’s IMAX unit and 3D and 4D films. That culminated in National Geographic Encounter, the 5,500sq m Times Square venue for Ocean Odyssey.

Working variously as producer, writer, director, executive producer and business exec, other spectacular results of Lisa’s work you might have seen, perhaps on a giant screen while wearing cardboard glasses, include DeepSea Challenge, reliving Cameron’s 2012 deep solo sub dive, and Sea Monsters 3D.

So now at Proteus she has to bring to bear all of her media creativity to ensure that it doesn’t end up as another of those “out of sight, out of mind” underwater projects.

As she intimated to Cousteau at the Explorer’s Club, by harnessing the latest in immersive technology Proteus could become a very public attraction – and that technology has been coming on by leaps and bound even since their discussions in 2020.

Built for comfort

“Prior habitats haven’t been designed for long-term comfortable human stays,” says Lisa. “Fabien set the record with his 31 days on Aquarius and by the end they were physically pretty uncomfortable, but there are simple engineering ways to make for a comfortable experience over much longer periods of time.”

The USA’s National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration might be expected to be a prime customer for such a sophisticated facility. “NOAA told us: we’ve been waiting for someone to come to us with a really focused business plan for a habitat for a long time,” says Lisa. “It was interested in the whole package but an important piece of that was that we had a bigger, more co-ordinated vision.”

The need for a habitat designed for the 21st century goes beyond ocean science, she contends. “That’s one really important aspect of the work that needs to be done – the missing toolbox, as Fabien says, of ocean science – but space industries, technologies, robotics, acoustics and many other industries are interested in working from this platform.”

Past projects carried out in saturation laboratories tended by necessity to be short, discrete and concentrated. “We’re looking at big, co-ordinated, long-term projects. Imagine that sort of work going on week after week, month after month, year after year and the kind of insights we can gain from that!

“Imagine Jane Goodall being able to visit the chimps in Gombe for only 45 minutes a day – we wouldn’t know much about the chimps or the ecosystems!” The long-term approach “opens the curtain on so much in the ocean that we have not seen or understood”.

Although Aquarius is relatively compact “there have been some important equipment prototypes tested and perfected and some really interesting scientific learnings that have come from that ability to be there 24/7,” says Lisa. “And, of course, it’s been the training ground for many crews of astronauts, who will tell you that it’s the best training for a space mission.”

The space industry is expected to provide a major revenue stream for Proteus. “Astronauts and folks in the industry tell us that, psychologically, if you know that if something goes wrong you can just open the door and leave, it changes everything.

“If you know you’re down there and have to solve the problems yourself, it’s very different. That’s why NASA has used Aquarius for all these years, because it really works.”

Space also brings with it many spin-offs that would be welcomed on Proteus. “Human-robotic coupling and pairing and gesture communication, life-support systems – oxygen, water, hygiene, food, waste systems, remote medicine – all the things you need to sustain life in space,” lists Lisa. “Much cheaper to test, tweak and modify them on Planet Earth before shooting them into space.

“All those things also have lots of applications for Earth. Anything you can do that improves water efficiency and energy applications could be interesting.”

The modular Proteus should offer the flexibility required to meet diverse users’ requirements. The original Proteus was, after all, a seagod with the ability not only to foretell the future but to shape-shift.

The ideal reef

So why Curaçao? “I can’t say enough about the island itself and how collaborative and co-operative the government is but, biologically, the really interesting thing about Curaçao is that it has a range of reef health,” says Lisa.

“There are only two accreting reefs in the Caribbean that are still growing – one is in Cuba, so not terribly accessible, and the other is in Curaçao.

“So we will have access not only to a relatively healthy and still growing reef but also to a whole range of degradation on the island’s reefs. Additionally, Curaçao has a fairly steep drop-off, which gives our scientists easy access to the Mesophotic Zone.”

This is the less-dived or studied layer of the Caribbean lying between 30 and 150m deep. It excites marine scientists for many reasons, not least for the potential offered by studying those mysterious areas that seem to defy climate change.

Proteus will be located less than a kilometre offshore, because of the drop-off – unlike the 11km-distant Aquarius. This should help in making it self-reliant, with what is said to be minimal need for surface support during missions.

As a recreational diver, however, don’t expect to take a week’s break in Curaçao and go wandering around the Proteus site as if it were some underwater sculpture park.

“Some of the work there will require isolation for the integrity of the science – you don’t want divers playing with your sensors! – and astronauts require a sense of isolation,” points out Lisa.

She does however expect there to be opportunities for “private aquanauts” to get to visit the habitat as part of science teams. This is the sort of approach that happens now in the private space industry and can, of course, prove quite expensive.

“We are also looking at having limited scuba or submarine excursions for non-saturation periods of time – up to 47 minutes – in which you can safely view the habitat. We do want to find ways that people can experience Proteus, whether through visiting or through virtual or augmented reality and so on.”

The Proteus concept involves rolling out a network of habitats around the world after Curaçao.

“We’re actively talking in the Middle East and in Europe, and a number of areas have reached out looking into putting one in their area,” says Lisa. “We’d like to branch out into very different eco-systems, perhaps a colder one – but initially we’re looking at warmer ones.” My money’s on Cousteau’s Proteus 2 being in the Red Sea.

On the money

Despite the welcome afforded to Proteus by bodies such as NOAA, raising the finances must have been challenging. “It’s not your typical investment, right? It doesn’t fit the mould of what investors are looking for,” agrees Lisa, clearly someone who relishes such challenges.

“We’ve had tremendous interest, and it usually comes from people who are looking to invest with purpose.” That means Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) investors, who assess a venture’s business plans in terms of sustainability and ethical standards.

“We were really successful in our early phase and now we’re moving into later phases of investment and have some exciting conversations going on – but it’s not the quick raise.”

In the 10 years since Cousteau conceived the project, and even within the four since he announced it, the world has changed hugely, the emergence of AI being an obvious example. I wonder whether such developments have compromised the original concept, but Lisa thinks the opposite.

“AI opens so many opportunities – you have to look at it as another brain you can bring down there,” she says. “We’ll have the ability to measure and study at a micro level that’s not really been done before 24/7 – and that means a fire-hose of data.

“AI is a fantastic tool to process that data and drive predictive modelling and analytics to understand what’s going on in the ocean in a new way.

“It’s a tool that makes everything we’re doing down there more effective. AI functions well only if it has great data and great inputs, and what’s missing in our oceans are the inputs – because we’re not there very much at the moment.”

Haven’t portable underwater data-gatherers such as ROVs, AUVs and manned submersibles also become more sophisticated and flexible? “Something NASA learnt in space was that it is at its most effective when it couples humans and robotics. It doesn’t send a human on a spacewalk alone and it doesn’t send a robot without a human for many things.

“There’s still an important role for humans in that data-gathering, in the interpretation. It’s only the human who knows to turn round and see what happened behind you when the data picks up an anomaly.”

Another undersea habitat venture has emerged recently in the form of The Deep in the UK. “I think it’s validation that this is an idea whose time has come, that there are others who see potential in this field,” says Lisa. “You can look on it as a competitive landscape or, as we choose to look at it, as a collaborative landscape.

“Anybody who’s working in the ocean in innovative ways is a potential collaborator to make us bigger, better, stronger, faster and that’s all in part because our real competition is against time.

“We’ve got to figure out what’s going on in the ocean and how we can protect it and keep it healthy pretty darn fast, because our lives depend on having a functioning healthy ocean.

“There’s training and technology we could share with each other, so much potential. You don’t want to be the only one doing something, because you turn round and say: wait, am I alone?”

Spreading the word

Cousteau claimed that some 330 million people had heard about his Mission 31 over the course of his month of submergence. The task with Proteus is to create another viable revenue stream by engaging the public in the habitat’s doings and keeping those people coming back for more.

Lisa Truitt, who agrees that with former undersea habitats “perhaps the storytelling could have been improved” has been working on how best to achieve that.

“It’s really important for us that people have access to Proteus – we want it to feel like an open platform, accessible to folks who can’t go down there.

“I’ve spent most of my life taking science and translating it into engaging stories designed to drive impact and to inspire. I moved into bigger and bigger playgrounds of storytelling, always with an educational component attached. That whole media landscape needs to reach different people in different ways.”

‘Edutainment’ is the buzzword. “Everything that happens on Proteus will be a potential story, a potential source of inspiration, and I think there’s room for that story on many platforms, from museums to theatres to TV sets to AR/VR and education.

“We can bring folks with different voices down to Proteus – storytellers, artists, poets, you name it, serving different audiences.

“There will certainly be live-streaming. That could get in the way on some missions and for some people, but it’s easy enough to work around that.

“Most scientists working in the oceans I talk to are really excited to raise awareness of the things they care about. It’s become a more and more important part of grant-funding that you also have a communication element.

“You have to talk about what you’re learning and doing in hopes of inspiring others. That’s what drives change.”

With technical staff resident in rotation on Proteus, there might also be an element of reality TV if they don’t mind becoming a part of the programming.

“Something unique that we bring to ocean storytelling is that human element,” says Lisa. “Proteus is a pretty spectacular project, like the ultimate sci-fi come to life, and I think that’s why we’re getting some of the interest we’re getting. It just grabs people’s imaginations.

“Proteus will give me a chance to play with new media and new environments that I haven’t used before, because media’s evolving all the time.”

Dream team

The Proteus core team currently consists of about 10 people, mostly full-time and from a variety of backgrounds, along with a wider set of advisors and partners.

“We’re in Curaçao regularly, though our scientists are there more because they’re deploying sensors and taking measurements, and our engineering team will soon need to be there more often too,” says Lisa.

Current on-site work consists of geophysical testing to design and deploy with minimal physical impact the habitat’s foundations. Then it will be time to start sinking its component parts.

Does the job allow Lisa to get under water? “I have dived in Curaçao but unfortunately in my role a lot of my time is spent in meetings. It’s all for the cause!”

The core team work remotely for the most part, connecting online from various parts of the USA’s eastern seaboard and Europe. Lisa is based outside Washington DC. “When the stars align and we meet up in Curaçao it’s like a big reunion, and super-exciting to share a drink on its shores.”

Cousteau she regards as the team’s ‘north star’. “Fabien is so inspirational, has such vision and passion for why this is important. I don’t think many of us really need to be reminded of why we care so passionately about the oceans and advancing ocean science and innovation but, if we do, he’s always there to keep us grounded, and is a great cheerleader.

“One of the guys always calls us the Ocean Science Dream Team, and I think we all feel that way. We’ve all become very close, driven by real passion and belief in what we’re doing.”

Also on Divernet: Proteus links with undersea warfare centre, Prpteus: Undersea habitat of the future, Cousteau closer to ’underwater space station’, Can underwater living turn Dr Deep Sea superhuman?, Shrunk but sleeping better, Dr Deep Sea resurfaces