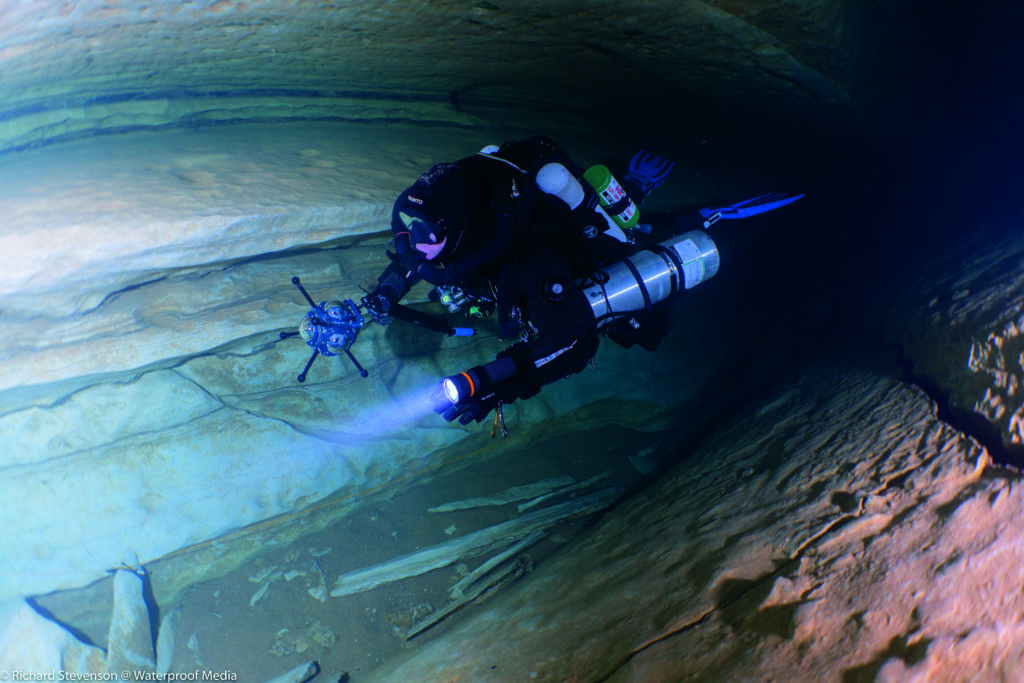

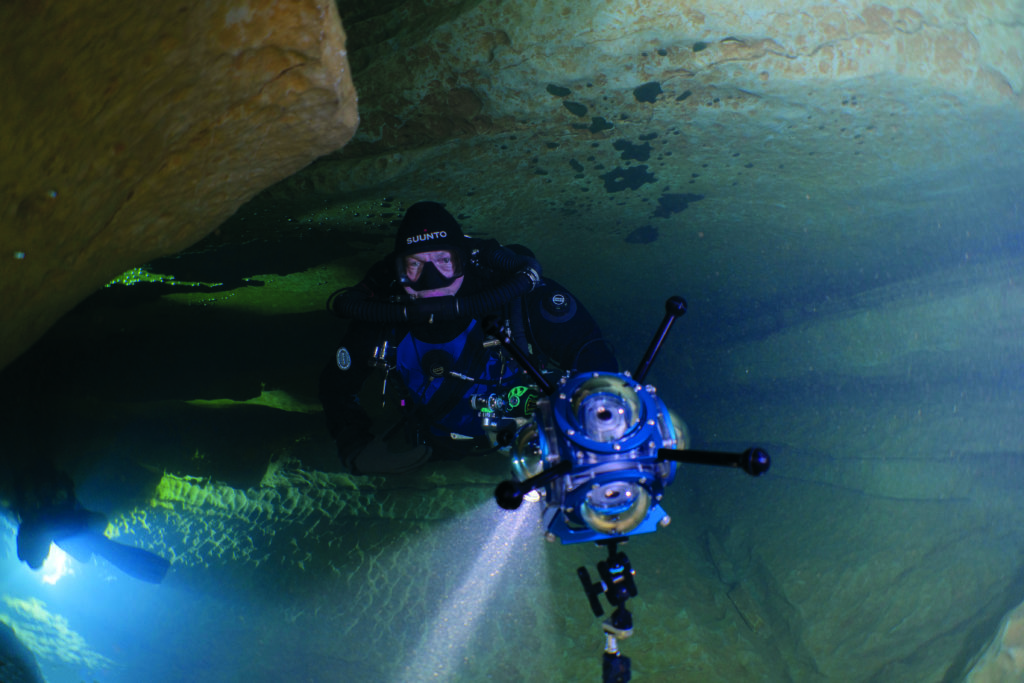

ANDY TORBET loves a challenge, so when Suunto threw down the gauntlet for him to produce a 360° VR short film he decided to try something different, and headed off underground in France with his crack team of cave-diving specialists. Photos by RICH STEVENSON

One of the biggest problems we face in film-making involving technical diving is light. Whether you’re 100m deep in the English Channel or only 100m inside an underwater cave or flooded mine, light is in short supply. And it’s essential when the camera rolls.

Also read: Dive Odyssey: Behind the Scenes

This problem is difficult enough to deal with when shooting conventionally, filming with a single camera in a single direction and the camera-operator can see what they’re filming. But suddenly none of this applies when you go 360, and it’s not the only problem you face when trying to shoot in all directions at once… while under water and under ground.

Tech diving for film-making

I had been tasked by Suunto to produce a film for people to view, either on their smartphone or using VR goggles such as the Oculus Go. This wasn’t aimed at divers so much as at the general public, to promote and inspire people about the possibilities and spectacle of the submerged realm. I believe the virtue of 360 is to transport someone to a place they could never otherwise experience.

I had seen previous underwater 360 film-making produced by divers on tropical reefs or surrounded by sharks in shallow waters off a Caribbean island. These are brilliant… but… you can see these things with the most-basic diving qualification, or even just using a snorkel.

They are also relatively easy to film, because the natural light that filters into the first few metres of clear blue sea illuminate everything equally well.

But at the time no one had taken on the challenges of trying to create a film to transport the viewer into a world very few people, even divers, get to see – I decided to take the camera cave-diving.

I expected to need a great deal of experimentation to work out how to light each scene and decide on camera positions and how the divers would move through frame. Going somewhere unknown would have added to the burden.

The caves of the Lot region of France are well known to British cave-divers, are easy to reach from home and have enough choice to offer something in good condition, regardless of recent weather.

I brought in Rich Stevenson, my friend and the cameraman I use most often on technical-dive shoots. He knows the caves of France well, has experience filming 360, is always up for the challenge of solving new underwater filming problems, and we’ve shot a lot together in some very dark places across the world.

We also needed a third diver to wield equipment, to help light the scenes and act as the third “star” of our film. Phil Short knows the French caves even better than Rich, and had been involved in filming operations in recent years. And the fact that we could all spend four days travelling and seven days living together without killing each other was a factor that should never be overlooked when putting a team together.

Setting up the camera rig

The camera rig would be set up on dry land and then sealed in its housing. This meant that we wouldn’t have the option to adjust any settings such as aperture or ISO that you would normally have control over with a conventional underwater filming camera. All we could do was press Record and Stop.

So Rich’s main task was less being a cameraman as a lightman. The influence over what was visible and what was not, whether it was under-lit or over-exposed and how each scene would look would all have to be controlled by the number, power and placement of the underwater filming lights – and where the divers shone their torches and moved through frame.

The type of specialist rig also meant that we couldn’t view, either live or in playback, what had been shot until we were clear of the water and had dismantled the housing and cameras.

It’s difficult for a director and, even more so, a cameraman to work when they can’t see what’s being shot. But I could describe in detail how I wanted the overall film to look and feel and then describe each scene, using storyboards, to match the film I had pre-edited in my head.

The mechanics of the problems that come with shooting 360 in a pitch-dark cave was not my, the director’s, problem. Under water, it would be Rich’s job to makes these difficult shots work.

After some recces and dives at other sites, we chose to concentrate on Emergence du Ressel. It is arguably the most popular and bwat-known cave-dive in France and was in the best condition of any site at the time.

It’s unusual in that you dive into a river to find the entrance/exit in the riverbed. There are a number of roomy passages, which gave us the working space we needed, along with large chambers and some vertical drops. The film needed to be only about five minutes long, but we needed enough variety to keep people interested and show them the real wonder of diving in a cave like this.

We had two methods for filming – hand-holding the rig while swimming, or having it stationary on a weighted tripod. The first full day was treated as a trial day. We would experiment with as many lighting configurations in as many different areas as possible. Without the ability to see what we were filming, we would have to make educated guesses, then check the results during the surface interval.

I had expected to write off the first two days at least in figuring out roughly the best way to set up each shot. Once we knew this, we would go back and film each scene using slight variations on these solutions, to give us a spread of options from which to choose.

As it was, Rich got pretty close to perfect on the first day. His time away from filming documentaries, instead working on dramas, commercials and feature films in underwater studios where “stage lighting” is part of the set-up, was coming in very useful.

Diving for each shot

We did up to three dives a day, most of them about two hours long, because we were restricted by the battery-life of the camera-rig and lights. We also didn’t want to shoot too much without reviewing the footage, so that we could apply any successes to other scenes, or limit the effect of any mistakes.

Between dives we would recharge the kit, review the footage as best we could (we couldn’t view it in full 360 on site), eat, drink and debrief. Then we’d plan and brief the next dive in detail and get back in.

Each scene had to be planned to ensure that, although the action would always be where the divers were, there was still something to see and discover wherever you looked.

This meant choosing parts where passageways met, making sure that we spread out in the larger chambers, or moved in a line with the camera hand-held by the middle diver. Even the distance between divers and the speed at which we swam had to be considered in order to show the scale, shape and orientation of the distinctive tunnels, shafts and rooms.

The editing process was also more involved than with a conventional film. First, all the clips had to be stitched together and their alignment corrected. Then, as with a normal edit, I’d go through all the clips and choose the ones I needed. I also tested some shots on divers and non-divers to see which ones had the most impact.

A surprising comment thrown up by some non-divers was that the sequences in which the rig was hand-held made them feel a little disorientated, and long sequences like this, or too many of them, would make them feel a bit sick.

After having viewed everything in 360, I would sent back the list of which parts or which clips I wanted in which order, and the editor assembled the final film. After a confirmatory viewing, to make sure that everything flowed well, he did the final polishing (adjusting levels, colours, contrast and adding music and titles) and the film was done.

Working in adventure and underwater media can look like an awful lot of fun from the outside. However, this isn’t always the case. There can be highs, but also many lows.

But with the interest created by having to overcome new technical challenges, a great product emerging in the end, the chance to work in one of Europe’s finest dive-sites and the chance to do it all with your friends… well, this job was exactly as much fun as it looks from the outside. In fact, more.

So whether you’re a cave-diver who wants to take a look at the famous Ressel, a diver who is thinking of venturing into cave-diving, or a diver or non-diver who just wants a glimpse into this alien realm from the comfort of your home, go to the Suunto Diving UK Vimeo Page and find the Suunto 360 Cave Video. You can watch it with any smartphone, preferably in the dark.

Also on Divernet: Do You Need To Be Fit To Dive?