WRECK DIVER

In the final part of a series of wreck-based articles that has spanned the past five years, JOHN LIDDIARD considers the continued diving legacy of the Great War after the Armistice

The German fleet

With the end of WW1, German warships were interned by Britain and France. The story behind the wrecks at Scapa Flow is well-known, so I won’t go into detail here.

The German officers and crews became tired of waiting for their fate to be agreed, concerned that peace talks would fail and that the Royal Navy would gain use of their ships. So on 21 June, 52 ships were scuttled. Many were subsequently salvaged, and now only seven remain, four cruisers and three battleships, at a perfect location for divers.

You can read more about these wrecks in Scapa Flow 100, Mike Ward’s feature in the June issue of diver.

While the best-known, Scapa Flow is not the only location where you can dive German warships sunk after the war. Scapa divers might have dived the turrets of the battleship SMS Bayern, the rest of the vessel having been salvaged for scrap, and Bayern ’s sister-ship was SMS Baden, scuttling of which was prevented by British sailors boarding and beaching her.

The Baden was subsequently refloated and in 1921 used as a target through two rounds of gun trials, testing new ammunition for the RN guns. After the second round, she was scuttled in Hurd Deep, a 180m-deep scour north of the Channel Islands. To my knowledge, the wreck has been dived only once.

For a more accessible wreck-dive, the light cruiser SMS Nurnberg was also saved from scuttling in Scapa Flow. Nurnberg was a light cruiser of the same Konigsberg class as the Karlsruhe in Scapa Flow.

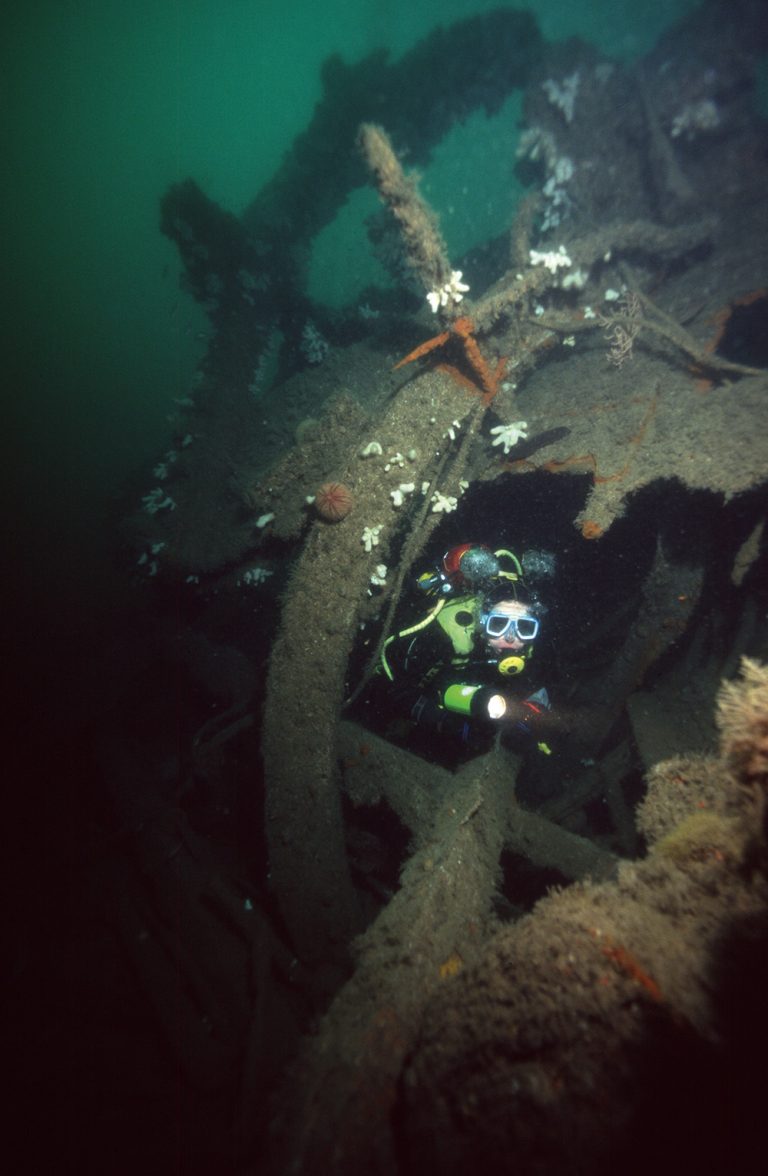

In 1922 she followed the Baden to be used for gunnery tests off the Isle of Wight. Fortunately for divers the wreck stands 10m clear of a 63m seabed, so is only just into trimix range.

It can be found mid-Channel between the Isle of Wight and Cherbourg.

U-boat disposal

It wasn’t only the fate of the German surface fleet that had to be decided.

Some 100 U-boats survived the war to be appropriated and shared out between the Allies. Many were simply sold for scrap; others were used in various trials before being scrapped.

Submarines are remarkably unstable to tow, and there are many stories of them breaking tow and washing ashore. Both U-118 and UB-131 washed ashore at Hastings, and U-118 became a summer tourist attraction. YouTube carries an old Pathé News clip from 1919.

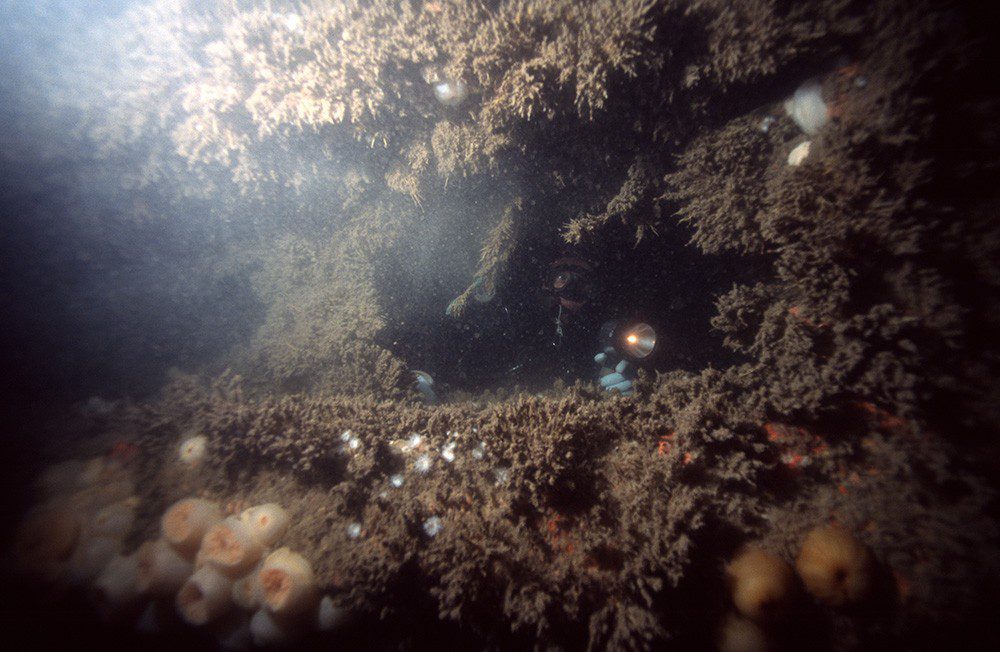

For those wanting to dive a sub, UB-130 sank in 1921 while under tow off Beachy Head. The wreck lies broken in 38m.

UB-122 suffered a similar fate while under tow up the River Medway in Kent but, at a tricky location on the mudflats, was never salvaged. Remains can be seen at low tide, but it’s not the sort of wreck-site you would want to dive.

A small flotilla of seven U-boats was taken to Falmouth to be evaluated. After various trials these were hauled ashore to check for damage. The wrecks were subsequently salvaged for scrap, leaving

a scattering of debris from the lower parts of the hulls in shallow water among the rocks. Mark Milburn provided the detailed history in diver, August 2018.

Much of the German U-boat knowledge and strategy in WW2 originated in the earlier conflict, and former U-boat commanders went on to play major roles.

Commander of the German Navy Admiral Karl Doenitz had commanded a WW1 U-boat, as had the head of the Abwehr, German military intelligence, Admiral Wilhelm Canaris.

M-class submarines

Having begun WW1 sceptical about the value of submarines, by the middle of the war Britain was developing new concepts in their design and tactics. One such innovation was the M-class, a large sub armed with a 12in battleship gun. The operational role was to pop up with only the gun showing close to a battleship, and put a shell through its side.

Four were ordered, but only M1 was completed before the Armistice, and saw no action. M-class was not a success.

The cumbersome gun armament was a liability, and improvements in torpedo technology made the gun obsolete.

M1 was lost in a collision with the Vidar off Start Point in 1925 as the steamship ran across the gun-turret, tearing it from its mounts and flooding the submarine. The wreck is diveable in 73m.

In 1925 the M2 was converted to carry a seaplane, with a hangar replacing the gun-turret.

On 26 January, 1932, M2 sank during a training accident, diving when the hangar doors were not fully closed. The wreck is now a popular dive in Lyme Bay, rising 10m from a 35m seabed.

M3 was converted to a mine-layer in 1927, then scrapped in 1932. M4 was broken up before completion.

Trains & train ferries

Getting supplies from Britain to the trenches was a complicated process. Freight trains would carry them to the docks; dockers would shift the supplies into the holds of cargo-ships; then, on the other side of the Channel, the process would be reversed for onward shipment by train.

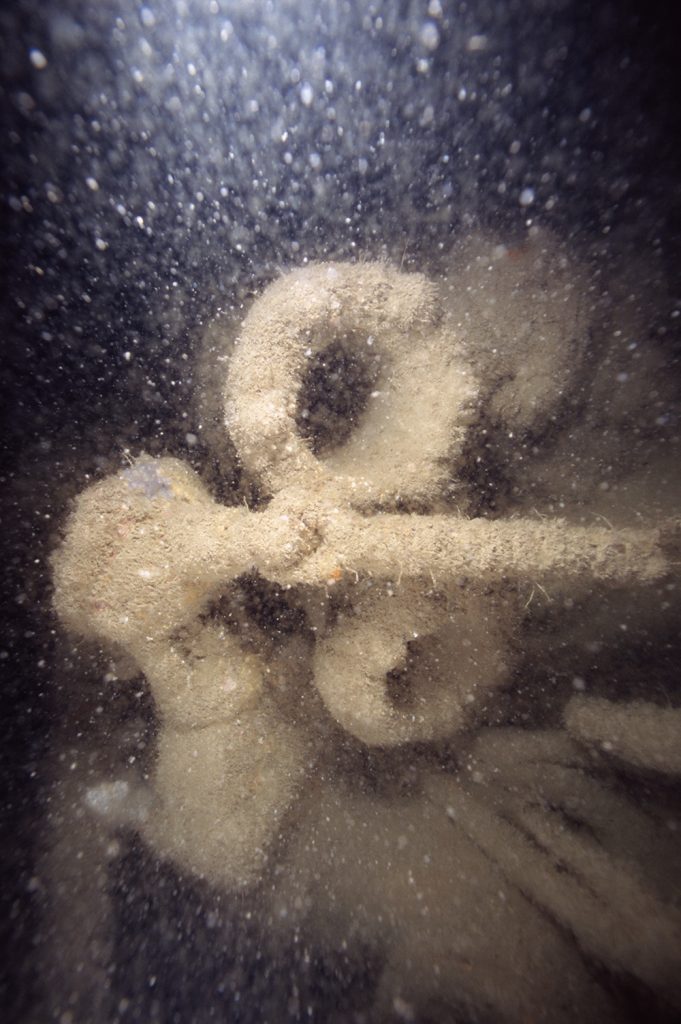

All that loading and unloading formed a bottleneck in getting supplies to the front. The concept of the shipping container did not exist. One way to speed the process was to unhitch freight wagons from the locomotives, roll them onto ferries, then hitch them up to form a new train on the other side.

With this in mind, the British Army ordered three train ferries: TF1, TF2 and TF3. All saw service in 1918 carrying freight wagons from Southampton and Richborough. After the war, they were sold to civilian ferry companies and ran cross-Channel services.

TF2 was lost off Normandy in 1940 during the evacuation of France, struck by onshore German artillery.

TF1 and TF3 were requisitioned back into military service and renamed respectively HMS Iris and HMS Daffodil. Both were converted to carry landing craft and supported the Normandy landings of June 1944.

Once ports were captured, Iris and Daffodil reverted to their original role to carry freight wagons across to France. TF3 struck a mine off Dieppe in March 1945, and TF1 survived the war.

TF2 and TF3 can both be dived in less than 20m off the French coast.

Standard ships on the slipway

From the opening of the U-boat campaign in 1914 the British Government started ordering new merchant ships from yards in the UK, Canada and neutral USA.

From 1916 these orders were for a few standard designs, predecessors of WW2’s Liberty ships.

When America entered the war in 1917, political obstacles to increased shipbuilding were quickly overcome, and massive new yards were established purely to build standard ships.

Ships already under construction were now requisitioned by Uncle Sam.

The largest of these shipyards was Hog Island on the Delaware river, a few miles from Philadelphia.

Among dodgy land deals, profiteering and alleged Mafia involvement, the first standard ship was launched at Hog Island on 5 August, 1918, but fitting-out was not completed until 11 November, the day the war ended.

With other ships under construction and orders too far along to cancel, 122 “Hog Islanders” were completed, with the yard being closed in 1921. Philadelphia International Airport now occupies the site.

Between Hog Island and other shipyards in the USA, Canada and the UK, 695 standard ships were completed. Only 14 were lost during the war, including the War Knight on the back of the Isle of Wight and War Monarch off Sussex.

But these are beyond the scope of this article, so it’s wrecks from among the other 681 that we seek. Standard ships were by far the greatest single type of ship for the first few years of WW2, and there were many losses in the depths of the Atlantic.

Fortunately for divers, some were also lost closer inshore. Only a wreck geek is likely to recognise the name War Buffalo, launched in Newcastle in 1918. Most divers will know this South Devon wreck better as the Persier, torpedoed by U-1017 on 11 February, 1945.

In February, 1944, off Haugesund in Norway, the Anne Sofie, originally the War Cove, ran aground and sank while carrying iron ore from Narvik to Emden.

As with many shipping “accidents” that occurred with Norwegian ships carrying German cargo, there were rumours of deliberate sabotage. The wreck lies on a slope from 37 to 52m.

For a real “Hog Islander” wreck, you need to go a little further, to Bali, where the Liberty Glo rests just off the beach at Tulamben. She was torpedoed by Japanese submarine I-166 on 11 January, 1942, while underway from Australia to the Philippines.

The damaged ship was towed to Bali and beached, where she was partially salvaged until a volcanic eruption in 1963 tipped her off the shore to rest just short of 30m.

While British standard ships were originally named War-something, names were changed as surplus ships were sold further afield. Sold to Japan, the War Lemur became Hokutai Maru and sank with the Japanese supply fleet at Palau during Operation Desecrate in 1944.

Following the D-Day landings of 1944, many old and worn standard ships served their last mission as Gooseberry blockships for the Mulberry harbours.

New owners for overseas territories

Before WW1, Germany was an imperial power with colonial possessions in Africa and the Pacific. For those who have dived the Pacific islands, the preponderance of coconut palms can be attributed to German colonial plantations.

From 1914 Japan seized German Pacific colonies and, following the Versailles Treaty, these were shared out between the winning colonial powers, the Mariana, Caroline and Marshall Islands being awarded to Japan. So at the time of the Pearl Harbour attack on 6 December, 1941, many of these former German colonies were now part of the Japanese supply chain.

For divers, the most significant are Chuuk (Truk) and Palau. In February 1944 a US carrier air attack destroyed a Japanese supply fleet at anchor in Truk Lagoon.

The following month, a similar air-strike at Palau sank a further supply fleet. Both are now major wreck-diving destinations.

Lesser-known Japanese WW2 wrecks are scattered through the former German colonies, locations that Japan controlled only as a consequence WW1.

Capital ships on the slip

It wasn’t only merchant ships that were ordered between 1914 and 1918. Many warships ranging from corvettes to battleships were laid down through the war, survived, and then became casualties of WW2 or later. Thus begins the story of the world’s biggest diveable warship wreck.

Construction of a pair of battle-cruisers was started in the USA in 1916, but then put on hold when the nation entered the war and resources were redirected to fast construction of smaller convoy-escort ships.

After the war, construction was resumed. Lessons learned about thicker armour and anti-torpedo bulges were incorporated into the design, only to be suspended again in 1922 before the Washington Naval Conference.

By 1919, most countries were pretty strapped for cash. To preserve the existing balance of naval power without starting an arms race, representatives of the UK, USA, France, Italy and Japan met in Washington and negotiated a treaty that limited the quantity, size and armament of ships each country could have over the next 10 years. The Washington Treaty was signed in 1923.

There wasn’t room in the US allowance for the two part-completed battle-cruisers. Construction of the two hulls resumed with a repurposing and major design change.

In 1927 the USS Lexington and USS Saratoga entered service as the biggest aircraft-carriers so far.

Even then, it took some dubious wrangling of the treaty rules on maximum size of carrier for them to be allowed. At 36,000 tons each, they were 9000 tons over the agreed limit – most aircraft-carriers were smaller, or only lightly armoured.

Lexington and Saratoga were as big as battleships and almost as well-armoured. It gave them a big edge in survival during the Pacific campaign. In the Battle of the Coral Sea, Lexington absorbed a tremendous number of bomb and torpedo hits before being scuttled to prevent capture on 8 May, 1942.

Through many battles Saratoga was hit and then repaired. Many times reported sunk by Japanese propaganda, she survived the war.

The heavy battle-cruiser armour made her so much tougher than other carriers.

In 1946 Saratoga was pensioned off as a target for the atomic bomb tests at Bikini Atoll – and still survived the first air-blast of the Able bomb.

It was the second underwater blast from the Baker bomb that sealed her fate, squashing and cracking the hull.

As well as being the world’s largest warship wreck, Saratoga is also one of the most exclusive. A dive-centre was established at Bikini in 1996 and ran successfully for 10 years, but the business had to close in 2007 when the supply chain became untenable.

Diving is currently possible for a couple of months of the year, through liveaboard trips from Kwajalein.

Also among the Bikini wrecks is the Japanese battleship Nagato, the flagship during the attack on Pearl Harbour.

Laid down in 1917 and completed in 1922, she was the only Japanese battleship to survive WW2, and another target in the atomic bomb tests.

Before WW1 Bikini was a German territory. Japan then took over and in WW2 the atoll was largely unused.

The six soldiers of the garrison committed suicide rather than be captured by the American island-hopping advance of 1944.

The USA wasn’t the only nation to repurpose capital ships as aircraft-carriers. In Britain, a battleship under construction for Chile was requisitioned in 1918 and completed as the aircraft-carrier HMS Eagle. She was sunk by torpedoes from U-73 in August 1942, while escorting a Malta convoy.

The Japanese Akagi was laid down as a battle-cruiser in 1920, but completed as an aircraft-carrier in response to the Washington Treaty limits.

Like Nagato, Akagi participated in the Pearl Harbour attack, then in April 1942 contributed to sinking the British carrier HMS Hermes off Sri Lanka.

Hermes was herself a Great War legacy, ordered in 1917 specifically as an aircraft-carrier. Construction was slow through many design changes until she was eventually commissioned in 1924. The wreck lies in 54m and can be dived from Sri Lanka.

A few months later Akagi was sunk in the depths of the Pacific at the Battle of Midway.

Treaty cruisers & sharks

It wasn’t only battleships and aircraft-carriers limited by the Washington Treaty. The USS Indianapolis was a cruiser built in 1930 to treaty limitations.

In 1945 the Indianapolis was used to transport the Little Boy atomic bomb to Tinian from where the B29 Enola Gay subsequently dropped it on Hiroshima. From Tinian, the Indianapolis went to Guam, and was then dispatched unaccompanied to Okinawa.

Just after midnight on 15 July, 1945, the cruiser was torpedoed by Japanese submarine I-58, sinking in 12 minutes.

With no escort and no distress call received, survivors were adrift for four days before being spotted by a patrol aircraft, most of them in the water.

Of the crew of 1200, only 317 were eventually rescued. Of the fatalities, about 300 went down with the ship and the rest died in the water awaiting rescue.

The deaths were mostly due to dehydration, exposure and drowning, with direct shark attack being a minority cause. Sharks, oceanic whitetips with a few tigers, largely fed on the bodies of those already dead. But the Indianapolis story was to fuel decades of frenzy against sharks.

In August 2017, the late Paul Allen, retired founder of Microsoft, located the wreck of the Indianapolis and filmed it from an ROV.

Combat swimmers

Looking back to 1 November, 1918, two Italian swimmers rode one of the first human torpedoes into the Austro-Hungarian naval base of Pola and sank the battleship Viribus Unitis with magnetic limpet mines.

Through the inter-war years the Italian Navy continued to develop human torpedoes, created the first diving watch and contributed to the development of rebreathers and other diving equipment.

By the start of WW2 the Italian Navy had become a specialist in this form of combat, attacking British ships in Alexandria and Gibraltar.

It was during the defence of Gibraltar that Lionel Crabb became famous as a clearance-diver, searching ship’s hulls for limpet-mines.

Initially Crabb used British equipment, but later used kit captured from the Italians. The remains of an Italian human torpedo can be dived in Gibraltar harbour, although there isn’t much left.

In response, Britain developed the Chariot, a slightly larger vehicle used in similar operations, principally in the Mediterranean.

Following the surrender of Italy in 1944, Italian frogmen worked on a joint operation with British charioteers to sink the Italian cruiser Bolzano, trapped in the German-held port of La Spezia.

The legacy of such commitment has led to many of our leading diving brands originating in Italy.

SO ENDS OUR ANNUAL REVIEW of the Great War from a diver’s perspective. Much of our diving results from this war’s conduct and consequences, and let us never forget those lost crews, as their legacy to divers rusts beneath the sea. The next time we run a series of features like this, it will be 2039…