Stories are often told of great shipwreck discoveries from the depths, but what of the wrecks that are most reluctant to reveal their whereabouts?

Leigh Bishop travels deep into the Arctic Circle in search of the one that really did get away – or did it?

THIS IS NOT X5. I REPEAT, THIS IS NOT X5.” A moment of silence passed before Carl responded:

“I can see that!”

The wreck appeared to be that of a small vessel with wooden teak decking, no more than perhaps 15m long. Small mooring cleats could be made out and then, as we reached one end, a rudder.

I keyed the microphone attached to my full-face mask: “That’s a small counter-stern. This is definitely not X5.”

Carl looked daggers at me, and I took the hint that it would be wise to say no more. We surfaced to see a sorry-looking TV crew.

They were no longer bothering to take the weight of their cameras on their shoulders. They had heard the bad news through the surface comms box.

After examining some 50 miles’ worth of data, we had travelled back to Norway in the belief that this small wooden sailing ship, which had collapsed down to seabed level with its mast at right angles, was our quarry – the midget submarine X5 for which we had been searching for the past few years.

It was a huge setback. The side-scan sonar image we had found hidden among all the data brought back from a previous expedition looked exactly as we would expect a fatally wounded midget submarine to look some 60 years after its sinking.

But instead of a small periscope mast, we had discovered a sailing vessel’s mast. The dimensions of this wreck, even down to what appeared to be saddle charges, had looked just like those of our target.

The whereabouts of X5 was one of the biggest mysteries of World War Two.

As we silently slipped out of our rebreathers and headed for the snow-laden shores of Kaafjord, every team-member knew that we had to get back to the drawing-board. X5‘s location remained a mystery.

OPERATION SOURCE was one of the most incredible of the war, the attack by Royal Navy X-craft on the German battleship Tirpitz.

The Admiralty hatched a daring plan to use the midget submarines to plant high-explosive mines beneath the battleship’s keel.

On 22 September, 1943, six X-craft set out from Scotland to sink her at her anchorage in Norway.

Three of the subs never reached the Norwegian fjords, and X5, commanded by Lt Henty-Creer, was presumed sunk by the Germans. Only X6 and X7 made the attack.

Both Lt Donald Cameron in X6 and Lt Godfrey Place in X7 placed their charges successfully, but were forced to surrender.

Both were awarded the Victoria Cross. Although Tirpitz was not sunk, she was put out of action until April 1944.

Lt Henty-Creer, the commander of X5, and his crew were never seen again. Neither he nor any of his crew received posthumous gallantry awards.

Did X5 actually penetrate the anti-submarine defences around Tirpitz and lay its explosive charges beneath the battleship?

If it did, then Lt Henty-Creer and his crew deserve to be honoured for their bravery. Could we locate X5 and possibly re-write history?

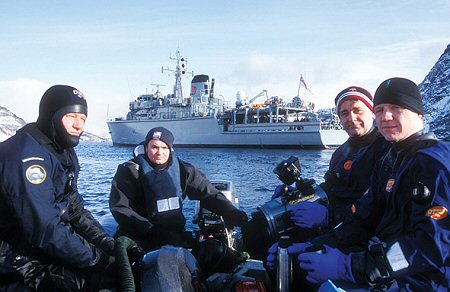

I was part of a British expedition to locate and vide- document the missing midget sub.

X5 was seen to have been depth-charged just 500m from where Tirpitz was anchored in Kaafjord, so the search was to concentrate on diving targets in Kaafjord itself, but could be expanded to adjacent Altenfjord.

There would be a side-scan and magnetometer survey team and a closed-circuit dive team.

Both had worked together on several projects, including the location and recovery of World Water Speed Record-holder Donald Campbell and his jet hydroplane Bluebird-K7, and a search for the minefield that sank the Britannic in Greece.

Our dive team didn’t need to be large. This was not a deepwater diving project, although it did come with its own technical challenges, in the shape of poor visibility, underwater search and location techniques, grid-mapping and, with surface temperatures below freezing, equipment issues.

Well-known divers marine engineer Kevin Gurr and boat captain Alan Wright would join Carl Spencer and me as the team chosen to rediscover the lost submarine.

Would it lead to a visit to Buckingham Palace and a belated VC for the families of the lost crew?

I made a visual check of Kevin’s Ouroboros CCR and ancillary equipment as he fitted his mask, then he and Alan went over the side of the boat kindly lent to us by Alta Diving Club.

Little is known of the movements of X5, other than that it must have penetrated Kaafjord, because shortly after 8.30am a third X-craft was sighted from the Tirpitz, about 500m outside the nets.

She was engaged and hit by the crew of the battleship, which claimed to have sunk the submarine.

Destroyers also dropped depth-charges in the position where X5 disappeared.

But had the craft only been wounded, and struggled back in the direction of its attackers? Our vessel was anchored up almost where Tirpitz would have been that day in 1943, as Carl and I awaited word from Kevin and Alan below.

Using their compasses, they searched the bottom at around 40m. Then Kevin’s voice came from the comms box: “Saddle charge, I repeat, saddle charge.”

They had located and ruled out an amount of unknown wreckage and then, only a few metres away, had come across one of the four saddle charges laid by X6 or X7, the only one that failed to go off.

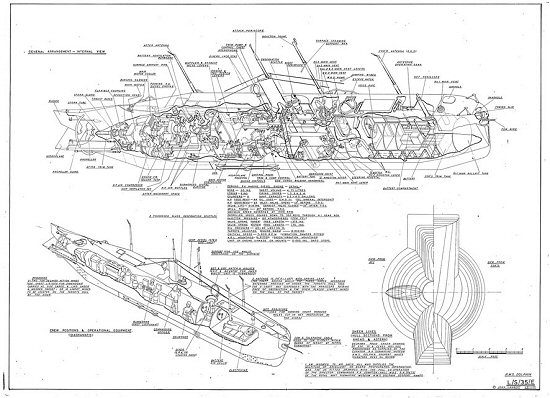

Each X-craft had two huge saddle charges bolted either side of the pressure hull, and once the detonation timer had been set these were to be dropped on the seabed beneath Tirpitz’s hull.

The three that did detonate effectively blew Tirpitz several feet out of the water, breaking her back. It was disappointing for the captured British submariners that she remained afloat, but she undertook no more operational duties during the war.

Six decades later, Bill Smith and his sonar team had collected a list of targets thought likely to be X5. All we had to do was dive and examine as many as we could in the time we had available.

BY NOW WE WERE IN our third year of diving. The sonar team were still finding anomalies on the seabed, but our targets were becoming ever-smaller.

Our first expedition had operated from aboard two Royal Naval warships, HMS Quorn and HMS Blythe.

After much correspondence with the Ministry of Defence, not only had permission been granted to search for X5 but, because of the significance of the search in terms of military history, the two warships had been assigned to assist us.

This was the first time Hunt-class destroyers had crossed into the Arctic Circle – some 400 miles inside it.

In fact the MoD and the Treasury had relocated an entire Royal Navy mine-clearance exercise from one area of Norway 400 miles further north to coincide with our activities. It was looking good!

PAP remote-controlled mine-disposal vehicles were launched from HMS Quorn to inspect targets, while the mine-disposal divers worked with the dive team to examine others.

Both methods would save valuable time.

Meanwhile HMS Blythe would, with millions of pounds worth of technology aboard, search the deeper adjacent Altenfjord.

We had made new Scandinavian friends who in turn had been bitten by the bug to find this midget submarine.

With quite a few kilos of explosives sitting somewhere at the bottom of the fjord, the project was also in the interests of the Norwegian Navy, which soon joined in the search.

DESPITE ALL THIS IMPRESSIVE TECHNOLOGY, we left the Arctic that year without a sniff of the missing X-craft.

A commemorative service aboard HMS Quorn was held for its lost crew, then we had returned to England to sift through the tons of data we had accumulated.

The following year we would continue our search, from the cold winter months when the warships had broken through the ice for us, to the summer.

We experienced 24 hours of daylight and sometimes dived under the Northern Lights, but still we found nothing! We started to doubt whether we would ever find X5.

I should mention that this venture could be regarded as a bit of a hand-me-down project.

Back in 1974, members of the British Sub Aqua Club under the leadership of one Peter Cornish had descended on Kaafjord in force to search for X5.

This was a milestone expedition for BSAC, one that located and, in 1976, recovered a section of X7, now on display at the IWM Duxford.

The story was covered extensively in DIVER’s predecessor magazine Triton.

The wetsuit-clad divers with their single cylinders and ABLJs had returned in vain year after year, just as we were turning up now with our closed-circuit rebreathers and drysuits.

Stuart Usher and John Harris, two members of those original expeditions who could not let go of the quest, returned to Norway with our team.

They were no longer diving, but brought with them valuable information gleaned from their extensive research all those years ago.

With their help we spent two weeks on site searching areas of the fjord and dive anomalies discovered by the Royal Navy and Bill Smith the year before.

Still nothing. Carl and I dived sections of German freighters sunk during British air raids, as well as unidentifiable objects dumped by the Germans during the war.

Once again time was against us, and we returned home at our wit’s end.

A NUMBER OF MONTHS PASSED, and my mobile indicated that Carl was calling me. “We’ve found X5,” he said. There was a pause before I replied: “What do you mean, we’ve found X5?”

“Bill’s found her on the northern side of Kaafjord.” An email followed with a side-scan sonar attachment showing wreckage on the seabed that looked very much like a submarine. How could everyone have missed this until now?

Not being a sonar expert I was still dubious about the image, but when the guys pointed out the various key points, the obvious saddle charges, periscope and typical bow section, I began to see what they were seeing.

With a TV crew looking to provide the perfect ending to a wartime documentary, tons of equipment was once again loaded onto our trucks, and we headed back deep into the Arctic Circle.

As the surface cameras focused on Carl and I, we checked our comms, switched on our HD underwater videos, completed our pre-breaths on our rebreathers and received a “good luck” from Bill Smith.

Then we descended to see for ourselves the original of the side-scan image we had been gazing at for the past few months.

The next words Carl heard from me were: “This is not X5, I repeat, this is not X5.”

The location of the missing midget submarine remains a mystery.

We have returned to Norway since examining that wooden-decked vessel and searched fruitlessly the final corners of Kaafjord. Where is X5?

Our avenues for exploration are now almost totally exhausted. We have one last location to search, and if that fails we can only conclude that X5 was hit so hard by the Tirpitz’s guns that the remains of the vessel have degraded and now lie sunk deep beneath the mud of Kaafjord.

If this is the case, this is where the X-craft will remain, as a war grave and forever untouched.

This article is written in memory of Carl Spencer who, before he lost his life diving Britannic in 2009, had made it his mission to find X5.