Why did Jacques Cousteau blank a scuba inventor reckoned to be decades ahead of his time? Who bribed divers to hand over their spearguns, only to bend them? And why did JOHN CHRISTOPHER FINE, who reflects here on some of the larger-than-life characters he has known in our sport, address freediving icon Jacques Mayol as Monsieur Rat?

“When I said to Cousteau that my name should appear on my photographs, that is when he pulled down le Rideau de Fer. It was the end of our relationship. He cut me off, simply because I wanted credit for my pictures.”

Le Rideau de Fer was “the Iron Curtain”, and these words were spoken by arguably the greatest inventor of undersea photographic technology of his era, photographer and film-maker Dimitri Rebikoff.

He was describing how Jacques-Yves Cousteau had wanted him to do the underwater photography for him, yet refused to give him credit for his photographs. “He would put his name on my work,” Rebikoff asserted. He never worked with Cousteau again after the Iron Curtain had fallen between them.

Egotism and fame can be synonymous in underwater endeavours, as it can in any sphere of invention, science, theatre or art. The greatest practitioners have been accused of double-dealing, of dishonesty in claiming inventions they never made, of taking the discoveries of others and reaching for fame over the crumpled lives of those that served them.

Behind the veil of courtesy are tales from the diving pioneers themselves, legends in their own right. They reveal minor scandals, infidelity, theft of ideas and work products; of great friendships, hardships, toil and death; of betrayal, as well as the wonderful fellowship of discovery as these divers descended into the ocean depths.

First reg & Didi Dumas

Philippe Tailliez’s early book Plongee Sans Cables told tales of going beyond the previous exploits of hardhat divers. Commercial aspects have changed since the early days of diving, when the very first men-fish fabricated their own equipment.

French Navy Commander Yves Le Prieur invented the demand regulator some time around 1937, with the tank worn in front. The device worked well, albeit uncomfortable to carry in that position.

Before the outbreak of WW2, a legend was born along France’s Mediterranean coast. Frederic Dumas, later nicknamed Didi, was powerfully built. He lived an uncommon life swimming offshore with his speargun, bringing back large grouper that astounded the people who gathered on beaches to witness his hunting prowess.

Didi’s adventures did not go unnoticed. French Navy officer Tailliez, who would watch him from the mountains overlooking the sea, took me to the very place where he first saw Dumas freediving, around an island off Toulon. Tailliez was a champion swimmer, and a man of uncommon talent for being out of step with his times.

Instead of using a boat to take him ashore from his naval vessel anchored in the Bay of Toulon, he would jump in and swim. Instead of going through the door to his lodgings, he would hide a grapnel in the bushes, throw it up onto a balcony and climb the rope to reach his room.

So Didi’s adventurous life appealed to him. Determined to meet the man-fish, Tailliez joined Dumas on his adventures along the coast – freediving, spearfishing and exploring places that fishermen saw only from the surface.

A man with a yen for photography was assigned to Tailliez’s ship. The young lieutenant saw this ensign come aboard the gangway, wan and weak. A car accident had almost cost Cousteau his arm and Tailliez, deciding that this young ensign needed exercise to restore his health, invited him to take part in their spearfishing exploits.

The Mediterranean is cold, and there was no thermal protection for divers at that time. The three men would gather on the beach after their long seawater exposure and build a fire, both to warm them and to cook their freshly caught fish.

A bond formed between them, and much later Tailliez would call them Les Trois Mousquemers – the three musketeers of the sea – and say that they had been “bonded by the salt of the sea”.

On one of those same beaches where the trio would warm themselves after diving, Tailliez and I built a little fire. It was winter and the air on the secluded Plage de la Mitre was cold. with a wind off the sea. We swam and snorkelled. Josie, his wife, made us a picnic lunch.

Eventually the three Mousquemers left us. First was Didi, who smoked unfiltered Gitanes one after another. His house in Sanary sur Mer on the outskirts of Toulon was hidden from view by an arbour that all but covered the entrance.

Once across the threshold, a warm olivewood fire greeted us with its savoury aroma. There was always coffee and fellowship among Didi’s intriguing collection of artefacts, gathered from around the world and lining his shelves.

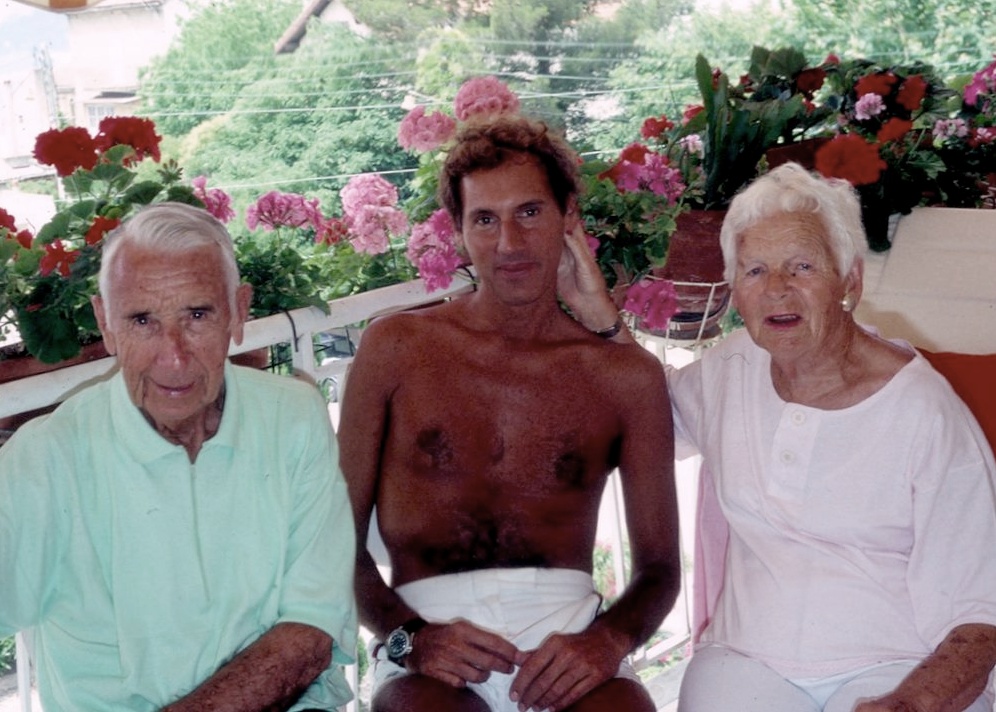

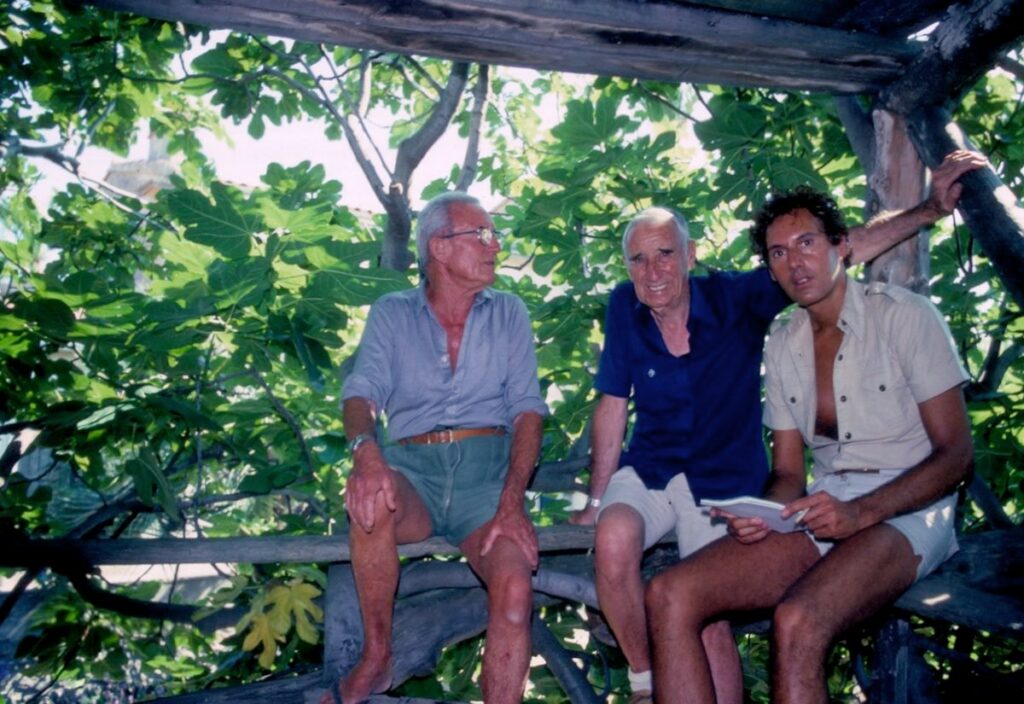

We would sit on polished logs in front of the hearth. Tailliez and Dumas would sort through stories of their lives, young men again in their minds. As often as not we would adjourn to the multi-levelled and amazingly spacious treehouse in Didi’s backyard. He had built it without damaging the tree in any way.

There we would sit and discuss projects. Didi would forever be enthralled with some new project, whether a proposed book, an exploit or a dream, and the treehouse was for dreaming. When I had had enough of his stories I would climb to the more precarious top of the treehouse, from where I could see the beach and the sea.

Les Trois Mousquemers

It was on a cold, rainy, fog-shrouded day that Tailliez came to pay his final respects to Frederic Dumas. We arrived very early and, amid dense mist, wondered whether we were in the right place. Of course we were – there was only one beach – but was it the right day, or had the weather forced cancellation of the memorial service?

Finally, in the distance, we heard music from a procession that had just reached the beach, from the plaza now named for Dumas, Sanary sur Mer’s most illustrious citizen. As Tailliez and I stood in the drizzle, the cold penetrating to our damp skins, an apparition arrived out of the mist.

“Jacques, Jacques,” Tailliez’s now-hoarse voice whispered. Cousteau had arrived to pay his final respects to the man most responsible for his fame and good fortune. The ceremony was long, yet seemed to disappear in the humility of the two remaining Mousquemers as they spoke, more to each other than to the other people assembled there.

When the ceremony was over, a friend offered the hospitality of his home on a nearby hill. It was welcome respite. He built a fire of olivewood and offered wine and food. The three of us warmed ourselves at the fire and talked. Tailliez and Cousteau were again the close friends they had been as young men.

In the distance a carnival was taking place. Organ music from a carousel echoed over the misty sea air to reach us in the hilltop house.

“Life is like that,” I remarked to Cousteau. “So many reach for the brass ring but never grasp it.”

Cousteau nodded, and thought deeply for a moment. Tailliez sipped his wine as the three of us huddled near the fire. “Yes,” Cousteau mused. “We reach for the brass ring.”

Many intimate stories passed between the two friends that afternoon. Private thoughts. Aspirations shared. Slights and misunderstandings of so long ago that Didi’s passing brought them back to the surface and revealed them to be of little importance now.

Indiscretions of many years past, of Cousteau’s mistress and infidelity to the beloved wife, Simone, who lived onboard his ship Calypso as nurse and mother to its crews. Loyalty had been paramount for Tailliez and Dumas, and disloyalty by Cousteau had resulted in years of isolation – now repaired in the rain as Didi was remembered.

The Hasses and Rebikoff

In those days, when I would make underwater documentaries and show them at film festivals around the world, I met many original pioneers of diving as friends.

Hans Hass and his wife and model Lotte were usually present at these gatherings. Hans made an early underwater movie with a housed camera he had fabricated. His German kept him somewhat aloof from the French, as the war had created a rift between their nations, if not the people. His films were milestones, although these early pioneers are no more.

Hans and Lotte’s glory continues unabated with fans who to this day celebrate their early successes. The Hasses were an alluring couple, as handsome in old age as they were in youth, still dedicated to conservation on land as much as for the oceans, though no longer diving.

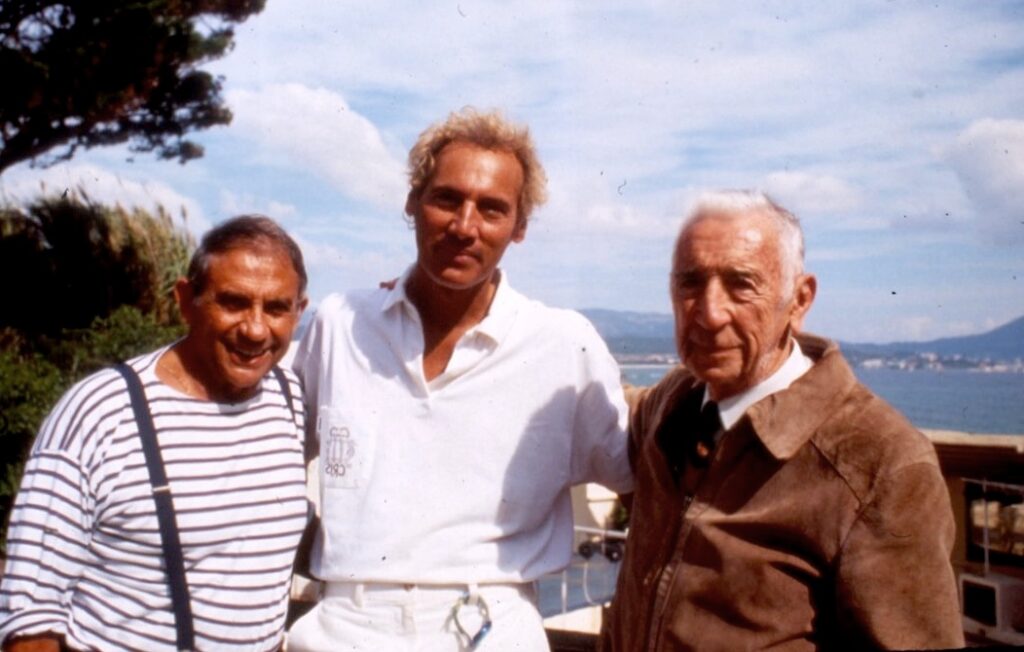

They were friends of the Parisian Dimitri Rebikoff, who had been born of Russian parents in France, so was French but also Russian. Alas, the great inventor’s ideas came 50 years to benefit him financially.

Captured by the Germans during WW2, he had been forced to use his inventive prowess to make radios for the military. After the war he resumed coming up with inventions that included the unidirectional diving bezel for underwater watches.

Dimitri met Ada Niggeler, who was German-Swiss and had a family villa just over the frontier in the Italian mountains. Ada became an accomplished diver and accompanied Dimitri on his many exploits around the world.

Dimitri and Ada would stay in a tent all summer long in a friend’s garden in Cannes. The Club Alpin Sous Marin was formed by diving enthusiasts and Rolex’s president would join the club on its outings. That’s when Dimitri proposed his bezel for the manufacturer’s watches, and the president told him that he would accept the design – but not patent it.

Dimitri’s concerns about losing out were wiped away when he was assured: “We won’t sell six of them in a year.”

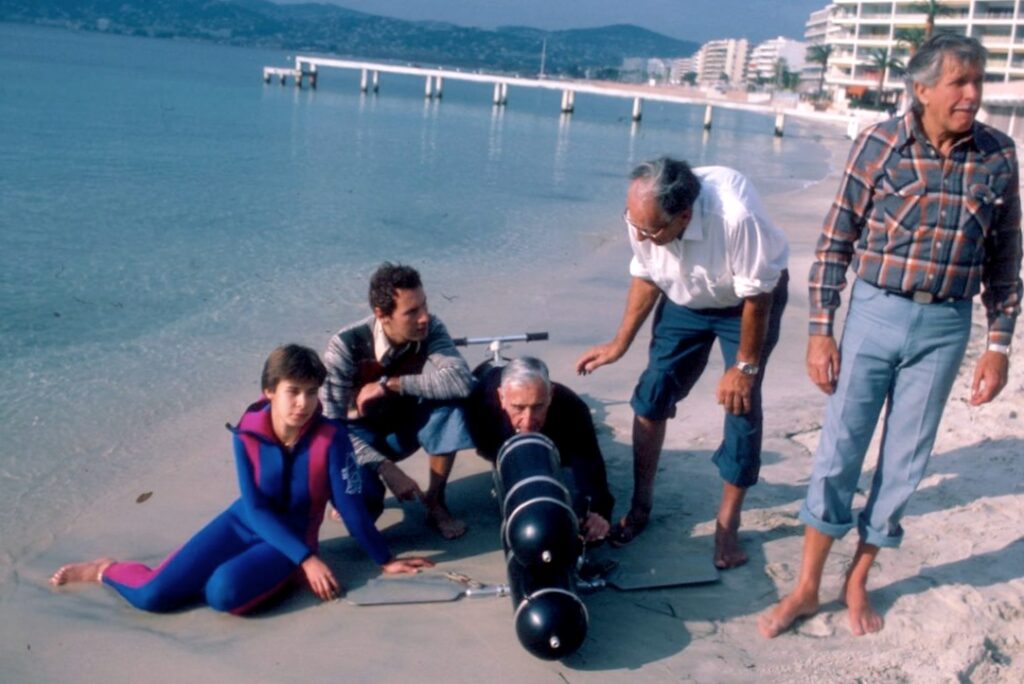

His genius also inspired the invention of the underwater electronic strobe, after he had taught ‘Papa Flash’ Edgerton to dive in the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) swimming pool, and the two men struck up a friendship.

Dimitri was first at everything, including his Pegasus DPV and the underwater cameras he fabricated from what eventually became his shop in Fort Lauderdale in Florida.

Jacques: Dumas & Mayol

Another Dumas unrelated to Didi, Jacques, was a successful Parisian lawyer. His civil practice and an inheritance allowed him to launch far-flung expeditions.

He filmed and photographed many of the shipwrecks about which he was so passionate from islands off Africa, exploring from the Malabar coast north to where Napoleon’s expeditionary fleet, sunk by Nelson, lay in Aboukir Bay, Egypt.

He was later elected president of CMAS, the World Underwater Federation. In 1985, when I organised and presided over the CMAS World Congress in Miami, the first time it had been held in the USA, he was due to meet me at the 10-day event.

I had arranged with an acquaintance at National Geographic to write an article about the exploration of Napoleon’s fleet, with Dumas providing the photography, but then the news reached me in Miami that he had died suddenly of a heart attack in Morocco.

CMAS was deprived of the dynamic leadership and legal and diplomatic skills of an experienced diver and active underwater film-maker.

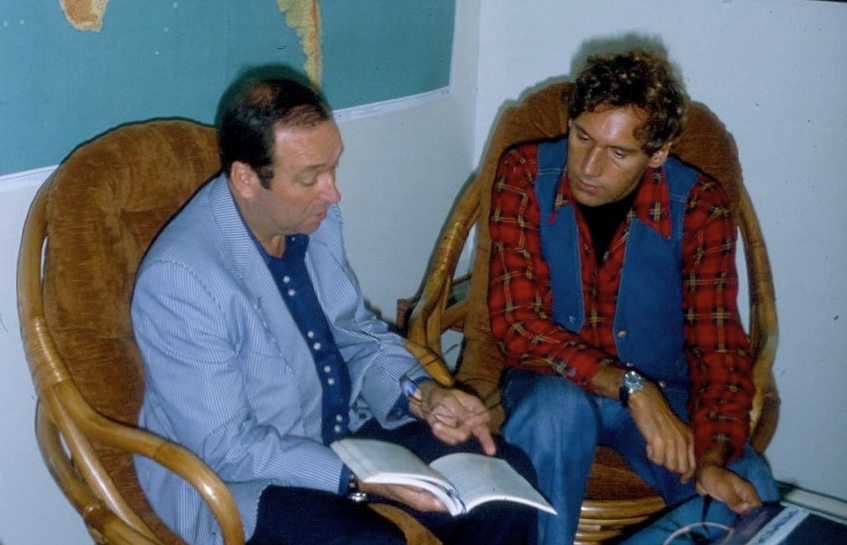

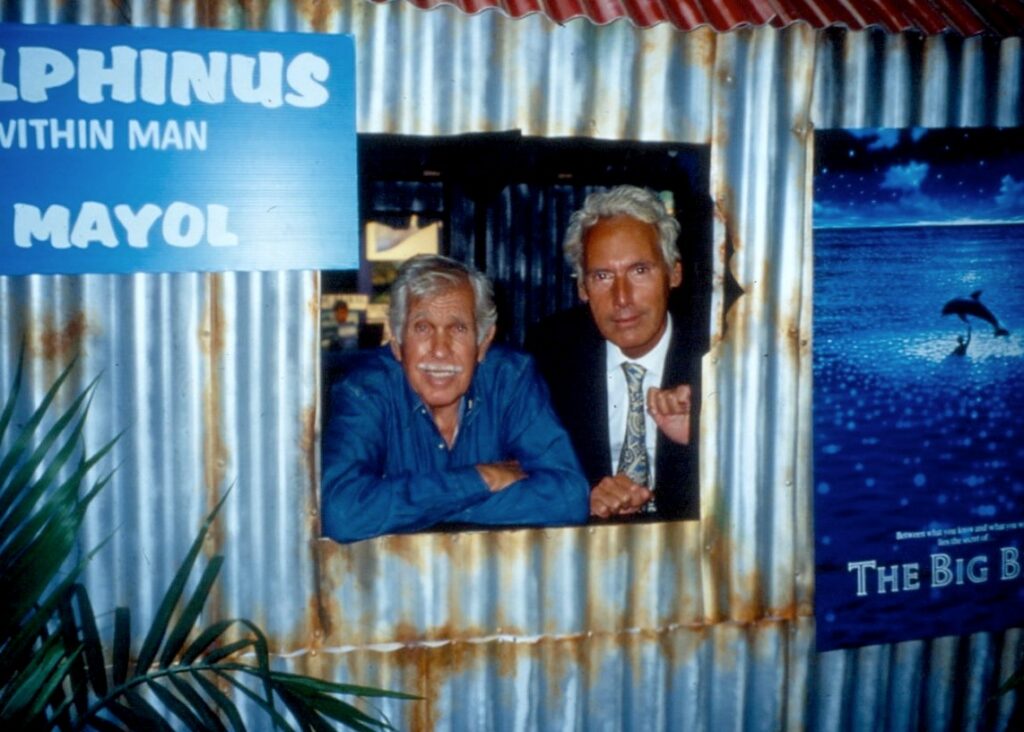

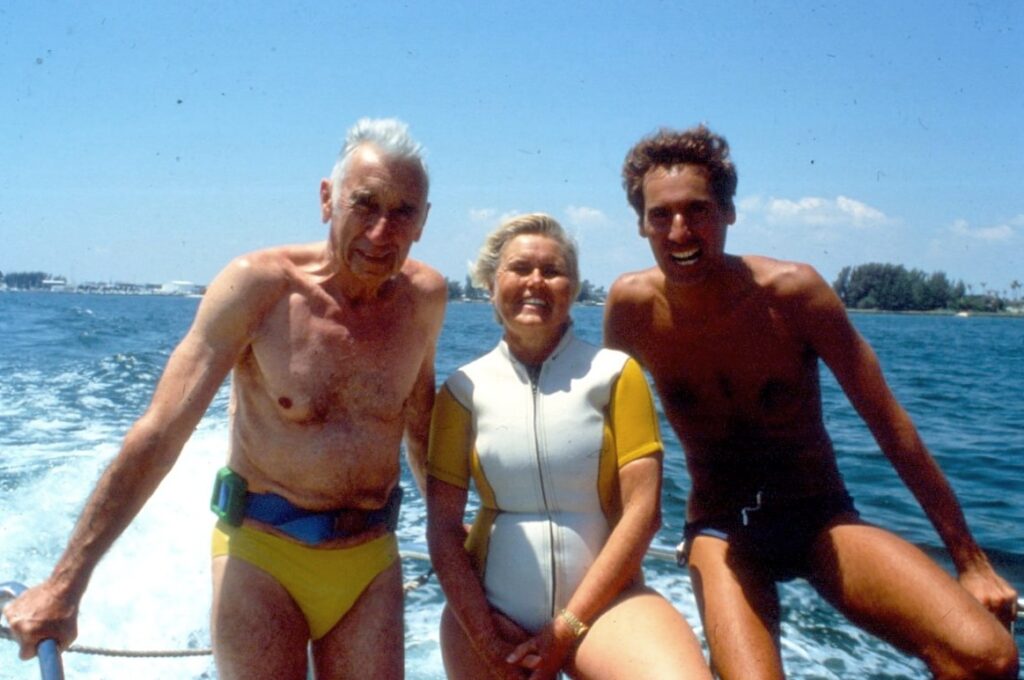

That alluring rascal Jacques Mayol was a natural under water and held the world breath-hold diving record. He was a celebrity, especially in Europe, and a character. He enjoyed the attention, but shunned the artificial. He cavorted with dolphins. I called him Monsieur Rat.

Why? Mayol had an eye for beautiful women and was rarely without one, even two, on his arm.

I had met a girl I was fond of in Juan-les-Pins in the south of France. Jacques and I had an appointment to do an interview with Radio Monte Carlo and we were driven to the station, but when we arrived Jacques opted out.

No amount of convincing by the director could persuade Mayol to do the show, so I went ahead alone, was picked up and brought back to a lunch that was already underway, where Jacques was sitting with my girl. In liquid French, I called him a rat.

Mayol didn’t get offended. He twitched his small moustache, smiled and said he didn’t mind because rats are intelligent. But: “Monsieur Rat, if you please.”

It was Monsieur Rat from then on.

The Stonemans and the gold divers

There have been many such characters in the diving world. Some are unsung heroes because they were not media hounds. They simply did their work in a craftsmanlike manner, like Ramon Bravo, Mexico’s greatest underwater cinematographer and TV personality.

Ramon started many novices on their careers, and Nick Caloyianis is one of his protégés. Ramon was justly proud of Nick’s film achievements.

John Stoneman, born in England but who moved of Canada, worked tirelessly, often through serious bouts of diabetes, to create more than 200 films for television, initially on CTV. John always sought an environmental theme or purpose for his work and would be relentless, often diving all day and into the night to complete a project.

Accompanied by his wife Sarah, John accumulated more than a million feet of documentary underwater film footage. Sadly a partner turned on him and, while John was away filming, he lost his entire archive.

While health concerns are keeping John out of the water, his protégé Adam Ravetch continues to film and explore the vast Canadian underwater northern wilderness.

Sarah Stoneman died recently, and the loss of this gracious and talented woman was a great sadness, because she was one of many who contributed to our knowledge of the world’s last frontier.

Others who have left us or, as former US Navy Commander and inveterate treasure-diver Bob ‘Frogfoot’ Weller would put it, “crossed over the bar”, include Mel Fisher, who came after Frogfoot was already exploring sunken Spanish galleons among Florida’s keys.

These were the halcyon times of discovery. “It was finders keepers in those days,” said Frogfoot. “The state didn’t really care about the shipwrecks. Not until we began bringing up treasure.”

Bert Kilbride was a living legend. He owned Saba Rock, not so much an island as a barren rock, in the British Virgin Islands. He took divers on excursions with his sons, also instructors. In fact his son Gary’s own son is the third-generation scuba instructor in the family.

Bert and I explored the 13-mile-long reef off Anegada. He had a Spanish galleon in the offing and many attempts were made to find it. There were plenty of shipwrecks but sadly no Spanish treasure.

The last time I saw Bert, he was speeding about in his electric mobility scooter. We were going to go back to Anegada and excavate his galleon. He assured me that he knew where it was – but he died with his secret intact.

Bending spearguns

Spearfishing was popular and profitable for dive operators. Although outlawed using tanks in most of Europe, US divers plied their trade on scuba off commercial dive-boats.

Norine Rouse would have none of it. She refused to take spearfishers on her dive-boats and offered a free dive-trip in exchange for a speargun, which she would promptly bent and set in a montage in the grounds of her Norine Rouse Scuba Club in Palm Beach, Florida.

It didn’t take long for divers to realise that while a dive-trip cost about $20, a speargun was only $12 – so they had a blast until Norine caught on.

Whenever British naval ships called in at the port of Palm Beach, Norine offered free dive-trips to the sailors, and always had a wide following from the UK.

She had started diving only when she was 40, having taught flyers before that and became an instructor, starting a small dive shop on Riviera Beach before organising what would become a country club for divers, including a deep tank training facility.

Norine loved marine turtles, befriended many creatures and defended the marine environment for years until a crippling decompression accident curtailed her diving. She’s gone now, but my dives with this pioneer of Palm Beach diving will always be memorable.

Bob Marx: ’Piss and punk’

We are all pioneers of a sort. Longevity means little. Discovery can be had on every dive, despite the fact that even virgin dive areas appear to be undiscovered until a beer-can looms large among the coral.

It is good to reminisce and remember those who have gone before, to tell their tales of high and low adventure.

To have laughed with the late Bob Marx, regaled by his pranks of youth when, as a young marine, he went diving only to miss his US Navy ship, and was thrown in the brig when he rejoined it on a diet of “piss and punk” – bread and water.

To voyage with the youthful Bob under water during the excavation of Port Royal, Jamaica, where a wall collapsed, pinning him under water and almost claiming his life.

Then there was Mike Portelly, a London dentist who found his passion in the sea and whose landmark film Ocean’s Daughter portrayed its beauty in a way that few before him had done. Fun to be with, jokes shared, pranks at international film festivals and always good cheer as he hosted our tiny film-crew in his London studio.

Not to be forgotten, either, the indefatigable Reg Vallintine, a bulwark of the British Sub-Aqua Club, author and grand host, who took me to dinner on a barge on the Thames after my long spell diving in Orkney, for the best meal I ever ate in England. Grand memories from long ago.

Set sail with these past divers through their books and films before embarking again on your own adventures. We are, after all, bonded in our pursuit by the salt of the sea.

Also by John Christopher Fine on Divernet: Cayman coral problems in black & white, Sea turtles on the brink, Deep Doodoo: Diver’s-eye view of a Florida problem, Coral farmers reshaping the future, Sponges: Glue of the reef, A dive pioneer turns 80 on Bonaire

What a great, in depth article.

Your readers might like to know about who invented the aqualung – the real story, on my blog here:

https://www.jeffmaynard.net/who-invented-aqualung/