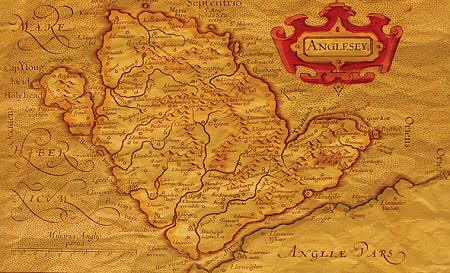

Is one of these privateers lying off Anglesey? Rico Oldfield has been beneath its waters in a bid to find out.

OUR WORK site is a bowl-shaped gully at the end of a long natural fault in the schist cliffs. Long parallel alleyways leading under water towards the cliff help to keep us orientated without constant reference to a compass.

Deep in these alleys lie the remains of what we suspect to be the bows of a vessel. And we have found that only one kind of metal detector is reliable under water – the most expensive!

But using metal-hits as datum points, we work in and out of these gullies, gradually removing and bagging portions of long-lodged concretion.

This is a shallow dive area, so we are at least aware of which way is up, no matter what the vis – which makes us feel more at home during long vigils working in a hole.

One of the welcome distractions that comes with laborious archaeological grubbing is the inevitable entourage.

From the corners of my vision, first come small wrasse and gobies, sensing food in the disturbed silt.

Satisfied that the small fry have attracted no hidden predators, the big guys such as ballan wrasse and pollack arrive.

Last, like thieves from the shadows, come the crabs, in a finale of furtive feeding. No chore is ever boring under water!

WHEN THE WEATHER RELENTS and the water clears around Anglesey, it’s easy to remember why we were first sold on diving.

Protruding as it does into the Irish Sea and its shipping lanes, it has wrecks galore, and because it lies between the Arctic and the boreal zones, its diversity of marine life can result in surprise encounters.

For sport diver and professional alike, the element of discovery is alive and well in these waters.

One of many surprising things the sea has taught me is that every shipwreck, no matter how battered by centuries of storms or plundered by generations of souvenir-hunting sport divers, retains some secrets.

Close to the popular tourist beaches of Treaddur Bay is a shipwreck that has always been known simply as the Cannon Wreck, or the Privateer.

Nothing of real value or note was ever discovered there, but the lure of eyeballing rusting cannons among rocks at the foot of the cliffs made it a popular shallow dive.

One frequent visitor early in his diving career was Jay Usher. Jay and I have been dive buddies for 30 years, and although our sport became a profession for us long ago, and has taken us to faraway locations, we often wondered about some of those early UK wreck sites – including the Privateer.

Years later, co-incidental research led us across time and distance to a surprising link between this wreck and the American War of Independence.

For the 17th century American colonists, victory in that war meant everything. For Britain, the worst that failure in battle could bring was losing a colony, but to the Americans victory meant winning a nation.

That perhaps gave them the edge that led to their ultimate triumph, but many aspects of the conflict were not in the colonists’ favour.

Britain took far more prisoners than the rebelling colonies, and detained them under conditions that caused grave concern to its enemy.

Thirteen thousand Americans are thought to have died in British prison ships, as opposed to just 4300 lost in battle.

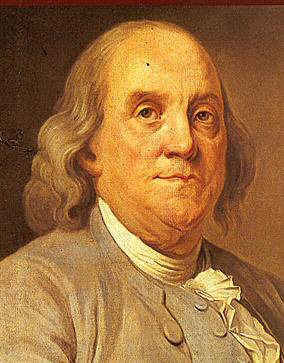

FOREMOST AMONG THE CONCERNED GODFATHERS of the American nation was Benjamin Franklin.

Popularly remembered for his amusing experiments with kites and lightning, Franklin was nonetheless a potent politician.

Faced with finding an answer to the prisoner-of-war problem, he came up with an imaginative plan.

He would commission a small fleet of privateers, one aim of which was to capture as many English seamen as possible, to be used as potential barter for American prisoners.

A tangle of politics and protocol was to frustrate this aim, but his privateer fleet would prove a worthy antagonist to the Royal Navy.

Almost all the vessels of the fleet were French-built and operated out of France. The first to be commissioned was the Black Prince, a 60-65ft sloop with between eight and 16 cannon.

It was joined by the bigger Black Princess, and the Fearnot was the last vessel to join the ranks.

Every ship was said to have had a black-painted hull, lending the small armada the notorious name of Benjamin Franklin’s Black Fleet.

Hunting in a stealthy threesome, this wolfpack proved as elusive as it was effective in harassing the British.

During the history of the conflict, the Black Fleet’s reported tally would include 76 vessels taken and ransomed, 16 brought in, 126 paroled, 11 lost or sunk and 11 retaken.

Any spoils were distributed between crew and owners. Franklin’s only share was joy at the political embarrassment his fleet inflicted on Britain.

The crews of Franklin’s privateers were not the brave American patriots you might expect. Franklin used Irish smugglers and pirates who knew our home waters as well as, if not better than, the Royal Navy.

Around 1780, records indicate that a “French privateer” raided Holyhead harbour in Anglesey and held either ships or the town itself to ransom.

The vessel was said to have fled before a storm to escape the Navy, and to have been lost just past the lighthouse known as South Stack – in the same area as our wreck.

Further research revealed records of an American privateer capturing two packet ships and holding them to ransom in Holyhead.

Overwhelming logic suggests that the two incidents are probably the same.

The datelines and storylines placed our Privateer wreck site as a convincing contender for a possible member of the infamous Black Fleet.

DEEPTREK IS AN INTERNATIONAL CONSORTIUM of professional divers from Australia, the USA and Britain.

One of my fellow-members is our chief marine archaeologist Jim Sinclair, and it was Jim, with his knowledge of American history, who unearthed this link.

It was unlikely that anything of value lay at this site, so there was no lure for investment in any kind of research project.

Our team had, however, been wanting to undertake expeditions under the heading “myths and mysteries”, to salvage not treasure but tales of adventure waiting on the seabed – and to make documentary films about them.

We felt that the Privateer site deserved top billing in a long list of hopefuls, so three years ago the team started gathering regularly in Britain to investigate the site and to test new equipment.

The work area soon earned the nickname “the Cauldron”. Tide and waves swirled insanely around the natural rocky crucible, often making diving tricky, even for experienced professional divers.

Rusting cannonballs and mangled iron combine with sand and rock over time to form the concretion divers know as “crud”.

Dissecting this unyielding layer with scientific precision took all our expertise. The extreme exposure of the wreck site meant that most artefacts found were extremely fragmented.

Nevertheless, the attention we were able to give these battered old vessel remains helped us to gather enough information to rate the Privateer as a genuine contender for the American connection.

The conclusive link to the Black Fleet has yet to emerge, but last year the National Geographic Channel saw enough substance in our research to film our diving operations for a TV production about Ben Franklin’s privateers.

Our first documentary had its US premiere in April.

THE VESSEL’S TRUE IDENTITY may yet have to be established, but a compelling clue remains.

My old friend Ken Berry lived in nearby Trefor on the Lleyn peninsula.

As well as being a fishing-boat skipper and auxiliary Coastguard, he was a diver for many years, and had extensive knowledge of local wrecks.

Ken had always referred to this wreck not as just the Privateer, but as the “Black Privateer”. Sadly, he died before this project grew wings, so what piece of information may have led him to refer to this wreck by that name died with him.

Not only do future discoveries lie unseen beneath the waves, but many an apparently well-dived wreck may still hide secrets that only the most obsessive history-detectives will uncover.