Three very different but compelling dives – a D-Day tank & bulldozer wreck-site, a big WW1 mule-carrier and an ancient man-made island in a Scottish loch – indicate the range of archaeological adventures that keep DUNCAN ROSS so busy

Scratch the surface a little, and the diversity of historical underwater sites in Great Britain is quite surprising. The most obvious are the shipwrecks lying within our coastal and, to a lesser extent, inland waters. Spanning at least two millennia, these alone provide a bounty of diving and research opportunities.

Beyond shipwrecks, there are aircraft sites, submarines, riverine sites, submerged forests, submerged towns, prehistoric landscapes, crannogs and much more. These sites are often scientifically and culturally important, so visits might require permission and, of course, due respect.

Through official archaeology projects and my own endeavours, I have had the privilege of visiting a wonderful variety of sites around the country, and they have altered my view of what British underwater archaeology is.

I have also made many new friends, increased my confidence and skills, and travelled to areas I would not have considered visiting before. Let me take you on just a few country-wide underwater adventures…

- 1) Operation Neptune Tanks & Bulldozers

- 2) 10km south of Selsey Bill, West Sussex, England, 2019

- 3) The background

- 4) The diving

- 5) ss Leysian

- 6) Abercastle Bay, Pembrokeshire, Wales, 2018

- 7) The background

- 8) The diving

- 9) Loch Achilty Crannog

- 10) Ross & Cromarty, Highlands, Scotland, 2022

- 11) The background

- 12) The diving

- 13) Getting involved

Operation Neptune Tanks & Bulldozers

10km south of Selsey Bill, West Sussex, England, 2019

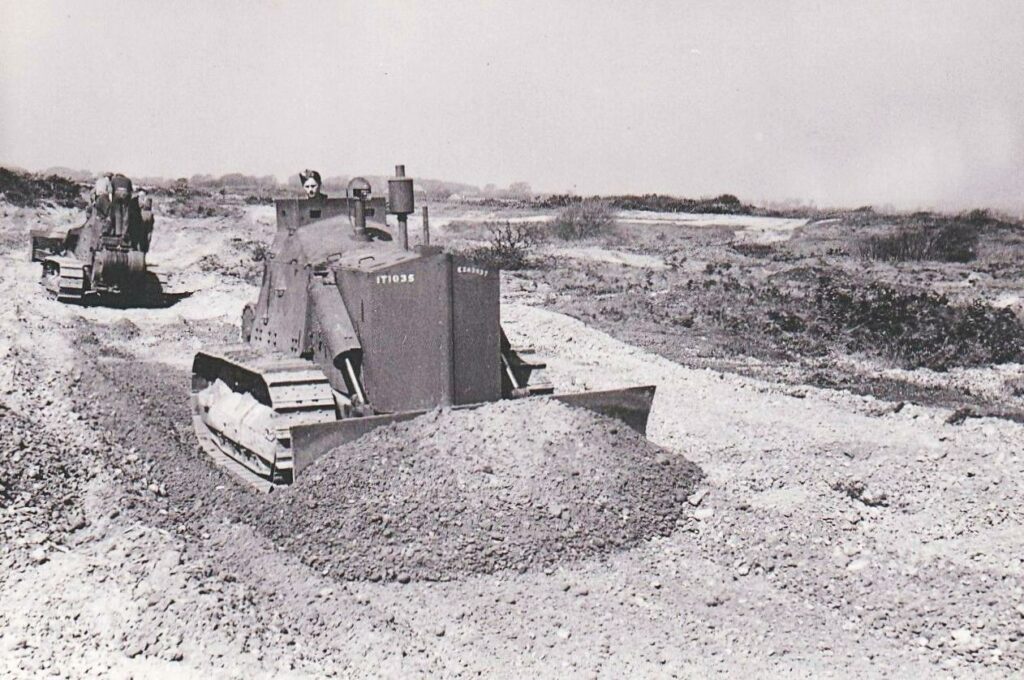

This site, covering an area of around 30 x 20m, contains not only tanks and bulldozers but many other bits and pieces that tumbled off Landing Craft Tank (Armoured) 2428 on the morning of 6 June, 1944 – D-Day. Divers can also visit the wreck-site of the landing craft itself, 6km further east.

LCT (A) 2428’s loading manifest included two Centaur Mk IV Close Support tanks with 10 crew from the 2nd Royal Marine Armoured Support Regiment, towing Porpoise Mk II ammunition-loaded sleds. Space was allocated for 50 rounds of extra ammunition stowed loose.

Also on board were two D7 armoured bulldozers with four men from the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division, and a Jeep with three crew from the 18th Canadian Field Company.

The background

The day before D-Day, LCT (A) 2428 was one of the 7,000 vessels of all types heading to the 10km stretch of the French coast code-named Juno Beach. At around 4pm the landing craft broke down, sprang a leak and was forced to turn back. By 9pm, now anchored near Nab Tower, it was listing to starboard.

The crew spent many frightening hours jettisoning gear and trying to plug the leak, but it was only at 9 the next morning, with fighting having raged on the Normandy beaches for about an hour, that the tug HM Jaunty was able to come to their assistance.

An attempt was made to tow LCT (A) 2428 but it capsized, spilling the rest of its payload onto the seabed. The landing craft floated upside-down for some time before Jaunty sank it with gunfire, to avoid it becoming a hazard to Allied shipping.

The diving

Dive-buddy Sara Hasan and skipper Mark Beattie-Edwards, both from the Nautical Archaeology Society (NAS), and I launched the RIB Honour from Eastney slipway in Portsmouth and sped out to our location.

It was a calm June morning, nearly 75 years to the day of the incident that had created the Tanks & Bulldozers site. With only the three of us heading out, we didn’t have to suffer the usual squeeze and shuffle of a full RIB.

Bouncing over the waves, I let my imagination drift, visualising black and white archive footage and famous war films such as Spielberg’s Saving Private Ryan depicting the Normandy Landings.

Our route would have been very similar to that of the armada of craft heading for the French beaches but, unlike the soldiers from 75 years ago, we were safe in the knowledge that we would be back from the site for our sausage rolls and sandwiches in about an hour.

Following the shotline, Sara and I descended through some 20m of green gloom. After lots of equalising and adding air to our jackets, familiar forms came into view – sharp angles, wheels, tank tracks, a turret, a bulldozer bucket.

Later that evening, watching my GoPro footage, I heard that I had let out an audible “whoa!” as all this amazing stuff materialised in front of me. A military vehicle museum on land is quite special but, under water, it’s something else altogether.

Staring up through the gaps between the tank tracks and wheels rewarded me with a spooky vista in which their ghostly silhouettes were etched into the dim light above.

The crusted metal of the vehicles, in some places rotted away after so many years on the seabed, demonstrated the ravages of seawater over time. One day, only piles of rust will remain.

Occasionally while Sara was exploring the other side of the vehicles her torchlight would dramatically backlight them, providing brilliant footage opportunities.

The upturned gun-turrets of the tanks were squashed into the stone and shingle of the seabed. The 95mm Howitzers had been specially fitted to provide extra firepower on the run-in to the beach.

Originally the tanks had not been meant to play any further part in the invasion but, during the following weeks, they had proved very useful.

The Howitzers – perhaps their most iconic features – were now bent and useless after sinking 20m and crashing to the seabed. They were intended to fire high-explosive rounds at German strong-points, such as pillboxes.

Many men had been onboard LCT (A) 2428 but nobody had died when it sank. As I drifted between the overturned vehicles, gawped at by monster-sized conger eels that had made the relics their homes, I thought about the many soldiers on the beaches who might have been protected by covering fire from the two tanks, and the obstacles that could have been cleared by the two bulldozers.

Surely, on the “day of days”, every item of equipment would have offered an advantage – or would it? Would a direct hit from one of these Centaurs have knocked out a German pill-box and destroyed a machine-gun post? Or would the beach have become even more clogged up with the addition of these four machines, hampering the advance further? Several accounts refer to vehicles jammed up on the beach.

Other things occurred to me, such as the intervention of fate for everyone on the landing craft. The sinking, although harrowing, potentially saved their lives by keeping them from the initial onslaught. They were, after all, part of the first wave at H-Hour.

What effect would the sinking have had on the psyche of the men on other landing craft as they passed the stricken LCT (A) 2428? They were in similar vessels, perilously overloaded in rough seas. Was there fear, a touch of envy even? What if their craft had broken down in the middle of the Channel, where rescue would have been even less likely?

Although meticulously planned, an invasion on such a scale was destined to falter at some level, and all military plans have an accepted casualty percentage.

The 105th flotilla of Assault Group J1 Support Squadron, of which LCT (A) 2428 was the original leader, was later cut in half and separated by a passing convoy of ships.

However well-trained and ready they were, the accumulation of problems would surely have added up to a general feeling of doubt and uncertainty for anyone in the 105th – not the ideal prelude to storming the beaches. War diaries state that wireless communication, vital to the landings, was onboard LCT (A) 2428 when it was lost.

Of the 306 landing craft destined for Juno Beach, 90 were damaged or destroyed.

Before we knew it, I was at about 100 bar and it was time to say goodbye to the magnificent tanks and bulldozers. Back on the RIB, I remember declaring it the best dive I had ever done, and it’s still right up there. I encourage anyone qualified to make the trip out to experience it for themselves.

As a result of my thoughts while diving, I set myself a research task. I wanted to find any stories from men who had made it across the Channel to operate D7A bulldozers and Centaur Mk IV (CS) tanks in the first waves to hit Juno Beach.

The D-Day landings are very well documented and interviews with veterans and first-hand accounts are fairly easy to find, and usually make sobering reading.

Most of the work and research at the Tanks & Bulldozers site has been carried out by Southsea SAC and the Maritime Archaeology Trust (MAT). Classed as a Scheduled Monument, it is regularly monitored to gauge its rate of decay and ensure that no interference has occurred.

ss Leysian

Abercastle Bay, Pembrokeshire, Wales, 2018

To mark the centenary of WW1, the Royal Commission on the Ancient & Historic Monuments of Wales devised the project Commemorating The Forgotten U-Boat War Around The Welsh Coast 1914-1918.

In conjunction with Malvern Archaeological Diving Unit and the NAS, a 10-day field school was run in Abercastle, and it focused on the wreck of the mule transport Leysian.

The background

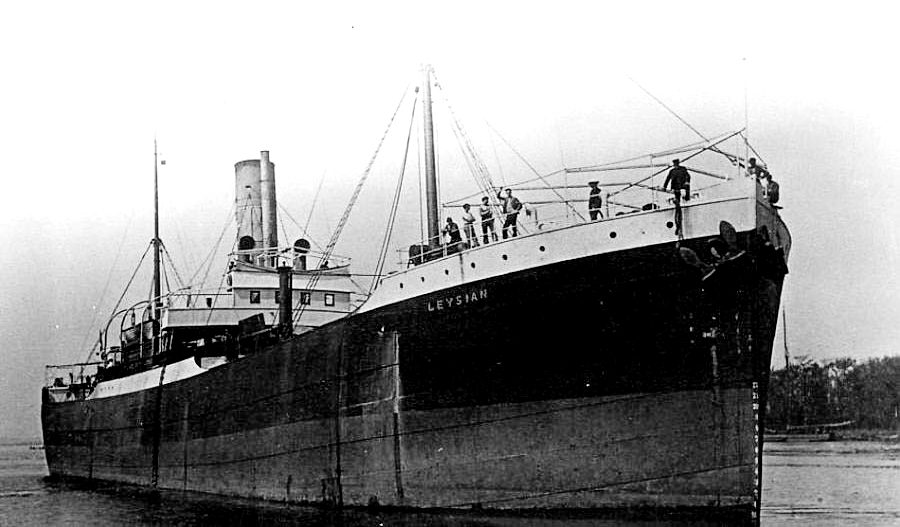

The Leysian started life as the Serak, built in Newcastle upon Tyne by Armstrong & Whitworth for the German Deutsche Dampfschifffahrts-Gesellschaft (DDG) Kosmos shipping line in 1906.

The steel Serak had two decks plus shelter deck and six bulkheads and, with dimensions of 122m with a 16m beam, was just under half the length of RMS Titanic – that is, substantial.

With three boilers, and driven by a 478hp three-cylinder triple-expansion engine through a single propshaft and screw, the Serak spent almost eight years transporting goods between Europe and the Americas before being seized by the British government at the outbreak of WW1.

Renamed Leysian, she was put into service as a horse and mule transport vessel. She ran aground in February 1917 at Abercastle while in ballast, with no loss of life.

The diving

Getting up close to a piece of history, half-frozen and half-erased by time, is a thrill that only seems to grow more fascinating as I forge ahead with my underwater-archaeology journey. After a year of intensive research into ss Leysian, to finally lay eyes on its remains in stunning visibility was a humbling treat tinged with emotion.

I whispered a fond hello as I descended to the remnants of a vessel the mysteries of which I had spent so many hours endeavouring to unpick.

Marking the central bow-to-stern line of the site, the enormous intact propeller-shaft lay exposed, flanked on either side by the flattened plates of the Leysian’s hull. The pock-marks of rusted windowless portholes were a ghostly indicator of the ship’s former life.

Time has not been kind to this vessel but it still possesses the otherworldly beauty that only sunken ships can.

To think that this jumble of jagged metal had once made the enormous transatlantic journeys I had read about, and carried all the people whose names had become so common in my day-to-day research – to the point at which I felt I knew the characters a little, and wondered about their lives – was quite special.

It was good to see that the Leysian was still serving a purpose; now as a busy marine habitat. Sea-life was healthy and abundant, and a few divers with sore fingers reported on how aggressively crabs were defending their little world.

My underwater archaeological task was to sketch anything that could add details to the as-then blank picture we had of the wreck-site.

Drifting back and forth over a section of the Leysian with my drawing-board, permatrace and pencil, I took in as much as I could of the site, but it was so vast that it was possible only to sketch a small portion of detail.

Quite baffling, it became obvious that many more visits would be required to complete such a gargantuan task. Around me other divers worked, some measuring distances between air-filled plastic milk-bottles tied to detail points.

The up-ended bottles waved gently in the current, a reference number written on each one in black for identification purposes. Each accurate measurement, in conjunction with others, would go towards refining the site-plan bit by bit.

Above, an ROV pilot navigated his expensive drone through the water, collecting video footage and sonar data. Among us below the waves, a professional videographer captured the dives in magnificent quality.

The experience was thrilling. I was part of a large team, one of a crew made up of amateurs, enthusiasts and professionals brought together by their shared passion for underwater archaeology.

Britain being Britain, the weather changed dramatically and I was able to take part only in that one dive – but what a dive! After all the research challenges, it was quite fitting that visiting the Leysian would not be a straightforward affair for me. To be continued…

Loch Achilty Crannog

Ross & Cromarty, Highlands, Scotland, 2022

In the summer of 2022, diver Richard Guest of the North of Scotland Archaeology Society (NOSAS) kindly invited me to take part in the Crannogs Project. The crannog in Loch Achilty had never been investigated in any kind of detail before our visit.

The background

A crannog is an artificial or semi-artificial island made of rocks, boulders, timber and mud that would at one point have been inhabited or used in some way by people. There is plenty of proof that some were lived on but, with so many variations in size, location, environment (wetland, bog, loch, estuarine), construction, age and assumed usage, the scope for interpretation and classification is vast.

For example, an entire wetland settlement was discovered at Black Loch, Myrton, whereas the Loch Achilty crannog (like many others) is relatively small, with space for no more than two buildings or structures.

A causeway path from the nearby shore to the island is generally thought to be a defining feature of crannogs but, again, many do not possess this, or else all traces have vanished over time. Some crannogs are also far from shore, making the existence of a causeway unlikely or impossible.

Classification issues are clear when searching for sites online. Enter the terms “crannog”, ”lake dwelling” or “artificial island” on Canmore (Scotland’s national record of the historic environment), and each one returns different results.

Various sources list the number of crannogs in Scotland as anywhere from 400 to 600, so there is still room for clarity. Brochs (stone roundhouses) and duns (a type of fort) also share many similarities and crossovers.

The Highland Historic Environment Record offers an age range for the Loch Achilty crannog spanning the Iron Age date of 550 BC up to 560 AD, but on what evidence is unclear.

Recent carbon-dating of associated timbers has returned dates relating to the mediaeval period, but that does not necessarily date the initial construction of the crannog. The official records will be updated in due course.

The diving

As I wound my way around the beautifully remote loch I knew I was in for a very special couple of days. It is surrounded by trees, hills and hardly any houses, and is not on the regular tourist trail.

Richard and the topside NOSAS team were not at the parking spot when I arrived so, after taking in some of the spectacular scenery, I put myself to work picking up any litter I could find. There wasn’t a huge amount, but it felt like an appropriate act of respect and repayment for the gift of being in such a tranquil haven.

Streams and run-off water both feed Loch Achilty, though strangely any water outlet has yet to be found. The loch’s level remains constant, so the crannog looks as it has done for centuries.

Richard and the team arrived, and we muddled a plan together that involved us being ferried out to the crannog one by one with our heavy gear in a very cute, if unstable-looking, vessel named Haggis.

Capsizing at some point seemed a given but, thankfully, it didn’t happen – good old Haggis. After 10 journeys to and from the crannog, however, it finally gave up and sprang a leak. From then on we relied on a super-fast canoe that shifted our efforts up a gear and more than met health & safety requirements.

One of our first “finds” on the crannog was, rather disappointingly, what a visiting dog had left for us. How it got to the island is another mystery to be added to the long list. Our thoughts were that it wasn’t from the Iron Age.

Entering the water from the crannog was going to be tricky, and the best we could manage was shuffling on our backsides down the slope before rolling sideways into the water. Ungainly, but we managed it without injury or causing any site disturbance.

We had no idea how deep the base of the crannog was, though 10m had been hypothesised, but after descending the north-facing slope into the depths, we realised that it had been constructed on the edge of a drop-off.

This gave us an initial false sense of scale, with the crannog seeming to go on forever. With a revised understanding of the layout, however, our diving became very easy – because we found the crannog to be only 2-3m deep.

At this depth, air clearly lasts a very long time, so we were able to explore the area at a leisurely pace. Crannogs built on precipices in deep water have been found in many other lochs, the reasons for this unclear.

The flattened cone of rocks was neat, with a definite circumference edge where it met the silted bottom. Many large pieces of timber surrounded the crannog, some embedded deeply in the loch-bed, some loose and some jutting out from within the rocks that could be imagined as forming part of the construction.

Do these pieces of wood hold special meaning, or were they once perhaps part of objects such as log-boats or land structures? Reusing building materials is a common factor with many structures.

Getting close to the rocks and timbers of an ancient crannog was a privileged experience, because nobody was likely ever to have seen before what we were looking at. Even the individuals who built the crannog wouldn’t have been able to view their work in this way. They would have been placing rocks fairly blindly, though with some obvious idea of their method.

Loch waters are known for being quite dark and peaty but visibility was more than adequate, allowing us to gauge scale, size and layout and to take clear photographs and film.

Curious baby pike spied on us from within the loch-bed foliage, indicating that there was definitely something bigger out there. Mummy or daddy were probably watching nearby.

The second day saw the topside team surveying and measuring the exposed above-water area of the crannog, while Richard and I further examined the timbers below the surface (dated as of August 2023 to the mediaeval period) that had stoked our curiosity the day before.

We briefly looked for the remains of a causeway but found nothing to suggest that one had been present. The bottom was heavily silted, so remains of piles could be buried deeper down. There was certainly nothing to indicate a drawbridge!

After we had recorded more useful video and photos, we surveyed the circumference of the crannog’s base by inserting canes into the loch-bed and taking measurements from the surface.

The first real Crannogs Project expedition, including underwater and topside surveys and a collaboration of organisations, went excellently. Richard’s team gave me a wonderfully warm welcome, and both days were full of humour, discovery and people enjoying their passion.

We enjoyed both good underwater visibility and temperate weather. Access was unproblematic, and it was a very positive budding of what will, I hope, bloom into a landmark project. My visit also provided publishing opportunities in the form of a Nautical Archaeology Society Sub-Aqua Club (NASAC) blog, later added to the NOSAS website.

Getting involved

Contacting any of the above-mentioned organisations is an excellent way to expand your own underwater archaeology experiences. The NAS, in particular, offers a huge variety of training and fieldwork opportunities around Great Britain and abroad. The three dives covered in this article are part of a bigger personal project that Duncan Ross is undertaking. Find out more about his Underwater Archaeology Tour on his Facebook or YouTube channel.

PADI Rescue Diver and underwater archaeology enthusiast DUNCAN ROSS has logged 330 dives over the past decade. A member of Chester SAC and NASAC, he is undertaking further BSAC training and has attained the highest NAS qualification, the Award in Maritime Archaeology. He has published many online articles about his underwater archaeology experiences.

Also on Divernet: Volunteer wreck-divers ‘unsung heroes’ – but new blood needed, Dunkirk wrecks project sets up 2024 dives, Get diving: ‘rescue archaeologists’ needed in Kent, Divers’ ancient finds confound experts

Great article, it definitely shows how much there is to explore on our own isles that we don’t know about!