When fish see scuba divers, can they work out exactly how many of you there are – and adjust their calculation if more divers join or leave the group?

Sting rays and cichlids are capable of mental arithmetic, researchers at the University of Bonn in Germany have just discovered. In a new study, the fish proved able to perform simple addition and subtraction in the number range of one to five – though what the scientists have yet to understand is how this mathematical ability would help them in the wild.

Animals were already known to be able to detect small quantities of items in the same way that humans can calculate a small number of coins at a glance, and sting rays and cichlids have been trained to reliably distinguish quantities of three from quantities of four – but what’s new is the discovery that the fish can also carry out calculations.

“We trained the animals to perform simple additions and subtractions,” said Prof Dr Vera Schluessel from the university’s Institute of Zoology. “In doing so, they had to increase or decrease an initial value by one.”

The experiments involved freshwater peacock-eye sting rays (Potamotrygon motoro) and zebra mbuna cichlids (Pseudotropheus zebra) and adopted a method employed previously to determine whether bees could calculate.

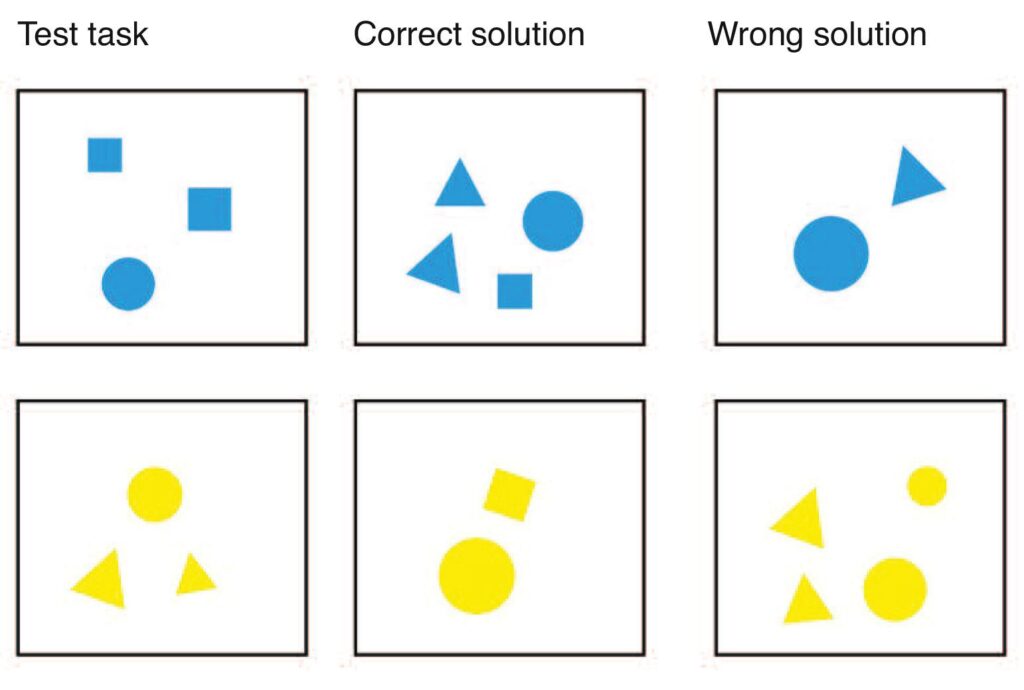

The fish were shown gates marked with a collection of geometric shapes, such as four squares. If the shapes were blue it meant “add one”, if yellow “subtract one”.

The fish were then shown a second gate in the form of two new pictures – one with five and one with three squares. If they swam to the correct picture (such as to the five squares in the “blue” arithmetic task) they were rewarded with food, but they went away unfed if they gave the wrong answer.

Deliberately omitted

Over time, the fish learnt to associate blue with an increase of one in the amount shown at the beginning, and yellow with a decrease – but the question was then whether they had internalised the mathematical rule behind the colour so that they could apply it to new tasks.

“To check this, we deliberately omitted some calculations during training, namely 3+1 and 3-1,” said Prof Schluessel. “After the learning phase, the animals got to see these two tasks for the first time. But even in those tests, they significantly often chose the correct answer.”

This was true even when they had to decide between choosing four or five objects after being shown a blue 3 – two outcomes both greater than the initial value. The fish chose four over five, indicating that they had learned the rule “always add or subtract one” rather than “choose the largest (or smallest) amount presented”.

This achievement surprised the researchers, especially considering that they had complicated the tasks by using combinations of different shapes such as variously sized circles, squares and triangles.

“So the animals had to recognise the number of objects depicted and at the same time infer the calculation rule from their colour,” said Prof Schluessel. “They had to keep both in working memory when the original picture was exchanged for the two result pictures. And they had to decide on the correct result afterwards. Overall, it’s a feat that requires complex thinking skills.”

The knack

Not every individual fish was good at maths (3 out of 8 sting rays, and 6 out of 8 cichlids were) but those rays that had the knack were correct 94% of the time for addition and 89% for subtraction.

Both species found addition easier to learn than subtraction, and generally the cichlids were faster learners, though this might have been because they had participated in previous cognition experiments.

Fish lack a cerebral cortex, that part of a mammal’s brain responsible for complex cognitive tasks, and neither rays nor cichlids are known to require good numerical abilities in the wild, but the scientists see the experiments as further evidence that humans tend to underestimate other species, especially non-mammals.

“They are quite far down in our favour – and of little concern when dying in the brutal practices of the commercial fishing industry,” said Prof Schluessel. The study is published in Scientific Reports.