On behalf of Divernet, historian DR KOSTAS GIANNAKOS and author ROSS J ROBERTSON sit down for an exclusive interview with diver extraordinaire KOSTAS THOCTARIDES, who discovered this long-lost submarine

Renowned Greek diver and researcher Kostas Thoctarides achieved the Holy Grail of wreck-hunting in June this year. After an arduous search spanning 25 years, he and his small team announced the discovery of the long-lost British WW2 submarine HMS Triumph, as reported at the time on Divernet.

The enigmatic vessel had vanished without trace, along with its entire crew of 64 brave souls, leaving behind a veil of mystery spanning 81 years.

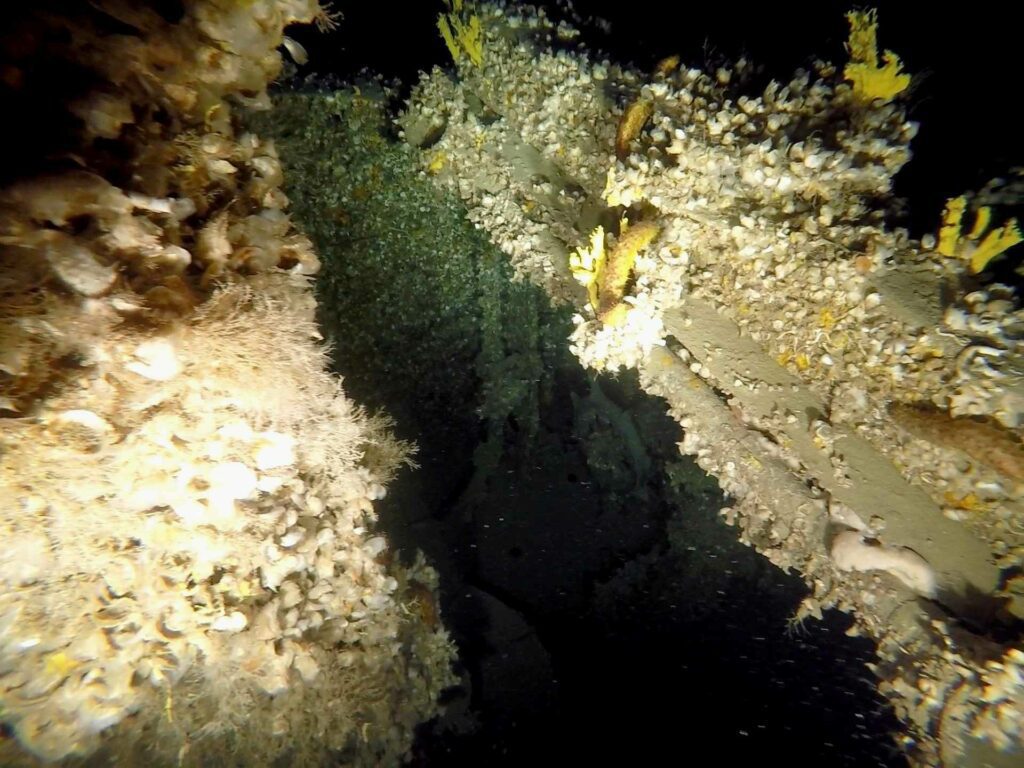

The wreckage lies virtually intact on the seabed at 203m in the Aegean Sea, several kilometres off Cape Sounion on mainland Greece. On the cab-bridge conning tower – a distinguishing feature of T-class submarines – the barnacled remains of a wooden helm and compass stand. Slightly lower is the 4in Mk XII deck-gun.

Tantalising clues to Triumph’s final moments are also evident. The periscopes are retracted and all hatches closed, suggesting a deep dive, while the rudders indicate a steady course. The door to the rear-facing starboard external torpedo-tube amidships is open, with a Mk VIII torpedo partially protruding.

The bow section has suffered catastrophic damage – but whether the cause was a shipping mine or one of Triumph’s own torpedoes is a curious matter yet to be resolved by the experts.

History of HMS Triumph

Having completed 20 war patrols, HMS Triumph was to return home to England under the command of Lt John S Huddart for a refit and some well-deserved R&R for its crew. At the last moment, however, it was diverted for a special mission.

Departing from Alexandria on 26 December, 1941, notable among those on board were Special Operations Executive (SOE) operative Lt George Atkinson; Greek secret service officer and former merchant navy wireless operator Diamantes Arvanitopoulos; and New Zealand MI9 liaison officer Lt Jim Craig.

Along with 5 tons of supplies, they were to be landed on the small Greek island of Antiparos. This was a rendezvous point previously set up by MI9 to evacuate British and Commonwealth evaders or prison escapees who had been left in Greece after the German invasion in April 1941.

Under the mission codename ISINGLASS, Atkinson was to proceed to Athens by caique. There, he would covertly meet leaders of two Greek resistance cells, collect additional evaders, grease the wheels with cash and gold sovereigns, deliver two all-important radio transmitter / receivers, and then return to Antiparos with the new evaders for evacuation.

On the night of 29 December Triumph reached its destination and unloaded the SOE / MI9 team and supplies. As many as 30 evaders, who had been on the run for months and waiting on the island for three weeks, expected immediate evacuation.

However, they could not be taken onboard because the Triumph was to embark on a patrol in the area first. Huddart promised to retrieve them on 9-10 January in the New Year. However, the submarine never returned.

The last communication was when Triumph signalled the completion of the first stage of its mission. It subsequently went on to execute its patrol. Records of a torpedo attack on 9 January, 1942 at 11.45am against the freighter Rea place it a few kilometres off Cape Sounion.

This is later followed by an Italian aircraft reporting a submarine sighting about 4 nautical miles south-east of Sounion. But neither of these facts was known to the Allies at the time.

As days turned into weeks, hope gradually waned. On 23 January the Admiralty reluctantly declared HMS Triumph lost, its unfortunate crew permanently consigned to the unknown depths.

Tragedy also befell ISINGLASS when members of SOE / MI9 operations, including Atkinson, were apprehended on Antiparos. Despite standard operational procedures, Atkinson had his written orders with him – and they contained vital intelligence concerning the Greek resistance, which subsequently fell into enemy hands.

The consequences were dire. With their cover blown and Britain’s reputation in espionage in tatters locally, many resistance fighters in Athens were rounded up. Most were condemned to the horrors of internment camps. Atkinson himself was put on trial and executed as a spy.

The interview

Incredibly, this is the fifth submarine Kostas Thoctarides has discovered in his career. In an exclusive interview, we asked him about his latest find.

What first got you involved with HMS Triumph, way back in 1998?

KT: “Shortly after I had discovered the sub HMS Perseus, I was invited to the British Embassy in Athens, where a well-informed naval attaché by the name of Benbow casually asked if I had heard of the Triumph. It was almost a passing comment, but enough to engage my curiosity. So I began to look into it. Naively, I thought it might take only a year or two – I was a little wrong about that!”

There were other attempts to find the submarine. Why do you think you succeeded where others failed?

KT: “It’s a combination of factors, including experience often gained the hard way. Access to primary sources, such as those at the National Archives at Kew, is crucially important. And for practical reasons, so too is easy access to the search area. Over-arching all this, however, is perseverance. The moment you decide to quit, then failure is 100% guaranteed.”

What were the worst challenges or obstacles in the process of discovering the submarine? How did you address them?

KT: “You have to understand that submarines are stealth weapons and are designed not to be discovered. So it’s virtually impossible when they go missing! But seriously… Although vital, the archival research was endless, not least as it involved thousands of files from British, German, Italian and Greek sources.

“Moreover, the Aegean Sea is a very big place and Triumph could potentially have been almost anywhere. So any snippet of information or possible clue had to be followed up to try to determine the sub’s last known location. Even so, the search area we had to physically cover was vast.”

Were there any breakthrough moments?

KT: “A torpedo attack on the Italian freighter Rea, which was being towed at the time, was reported to have taken place on 9 January, 1942. We searched the area and found three Mk VIII torpedoes. They hadn’t struck a target, and their propulsion ran out and sank.

How was the search funded? Privately, or was there government assistance from either the British or the Greeks?

KT: “It was funded entirely by me and my passion for exploration! That’s sometimes not easy, I admit. Fuel costs in particular have become crippling. Boats are inherently expensive and wreck-finding equipment is also a major expense although, if you are judicious, there are ways of staying within a budget.”

How so?

KT: “A lot of high-end specialist equipment is available these days. Most is very good, but prohibitive in cost. I have a side-scan sonar, but it’s only useful at comparatively shallow depths. So I principally use a far cheaper fish-finder sonar.

“Normally, serial numbers should be checked, but that’s extraordinarily dangerous as such torpedoes still contain explosives. However, we understood they were the exact same type as those used on Triumph. That’s when I knew we were getting close.

“It has been tweaked a little to help find metal, but it’s pretty much the same used by fisherfolk. It has proven good enough to find Triumph and many other wrecks.

Marine archaeologists and academics are the professionals in the field of maritime history, yet it’s often left to private individuals and enthusiasts – so-called wreck-hunters like yourself – to discover wrecks at their own expense. What’s your view on that?

KT: “Offhand, I would say that it’s a missed opportunity. Although dives and research is undertaken by such experts, more could undoubtedly be done. That would mean more funding, and that’s only possible with a bigger vision. Marine archaeology is part of a shared cultural heritage – it belongs to each and every one of us. It should be publicly funded accordingly.”

Can you describe the moment of discovery?

KT: “There had been quite a few close calls in the past, but somehow I found this one exciting. We’d sent down the ROV and were transfixed on the monitor. Sonar had told us there was something quite large down there, but what was it exactly?

“Then, the moment of truth – the ROV lights caught something in the pitch darkness. After a little careful manoeuvring by my daughter Agapi – she is Greece’s first certified ROV operator, by the way – it became increasingly obvious that we were looking at some kind of shipwreck.

“First we saw the stern then, amidships, the unmistakable conning tower of a submarine appeared. An awe-inspiring sight, I can tell you!

“But I must also say that the instant I saw a closed hatch, I was struck by the thought of those who had been trapped inside so many years ago. So, extreme excitement that our quest was finally over, but it was also something of a bittersweet moment because of the meaning of what we’d found.”

There are quite a few sub wrecks in the Aegean, U-133 is not that far away and the Greek submarine Katsonis was discovered quite recently at 250m near Skiathos. How did you determine that it was HMS Triumph?

KT: “Obviously, we knew from the archives what we were looking for. So it was a matter of matching features with those of a T-class generally and Triumph in particular. Repairs after striking a mine on 26 December, 1939 in the North Sea meant that she had a truncated bow and did not have external bow torpedo-tubes, nor did she have aft torpedo-tubes, so these were major identifiers.”

What happens to the wreck now?

KT: “Under UNESCO and Underwater Cultural Heritage rules, the submarine is automatically designated a war grave and assigned the status of a site of archeological importance. Additionally, its depth does not make it easily accessible, ensuring its preservation.”

Is your work done with the Triumph?

KT: “Not exactly. We continue to work in collaboration with submarine and torpedo experts, especially regarding the powerful bow explosion. The reaction to the discovery has been tremendous.

“Perhaps ironically, it has elicited many questions from the families of the crew on board. However, now that it has been found, I’m very confident that the last secrets of HMS Triumph will be unravelled, and closure can finally be achieved.”

The singular efforts made by Kosta and his small entourage over so many long years bear testament to the fact that perseverance is a key ingredient in wreck-hunting. Without such dedication, what transpired all those years ago would still remain lost in the mists of time.

Indeed, the wreck stands as a poignant reminder of WW2, evoking both reverence and awe. It instils within us a profound appreciation for the valour of those who served in the submerged shadows of a war beneath the waves.

Also on Divernet: Views of the Volos, The O2 Rebreather Miracle, Greek wreck-hunter solves 1959 mystery, First freedivers visit ‘Great Escape’ sub, Tech divers untangle Perseus sub

I admire the work done to find HMS Triumph. The closed escape hatch sadly speaks volumes,