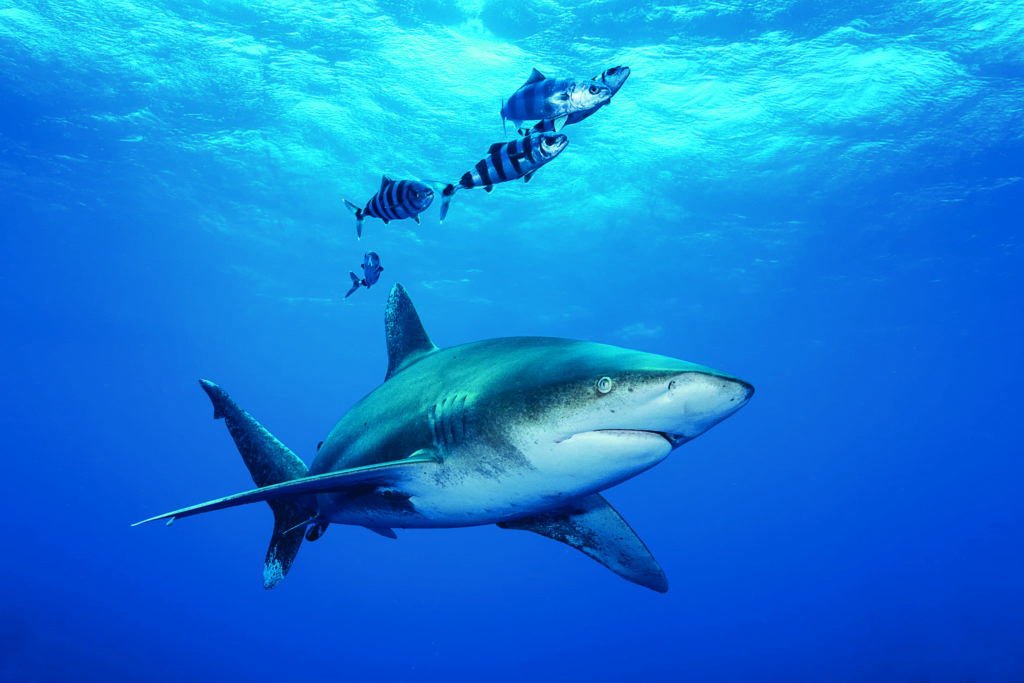

- 1) Roaming free

- 2) Oceanic whitetips as bycatch

- 3) Hope springs eternal

- 4) Underwater encounters

- 5) Cat Island

- 6) Pregnant females

- 7) How it works

- 8) Great hammerhead sharks

- 9) South Bimini: Great Hammerhead Central

- 10) Why South Bimini?

- 11) Face to face

- 12) Feeding time

- 13) After Dark

- 14) The ethics of it all

- 15) Shark ambassadors

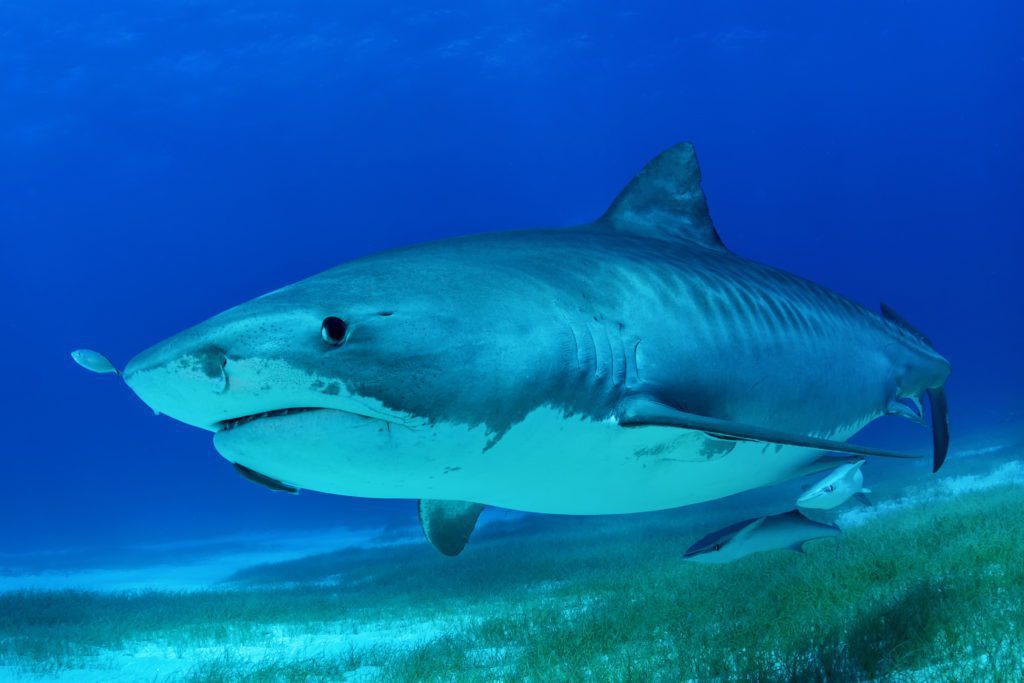

- 16) Tiger sharks

- 17) Tiger Beach isn’t a beach

- 18) Understanding Tiger Beach

- 19) Eye of the Tiger

- 20) Petting zoo…

- 21) …or real deal?

DON SILCOCK heads to the Bahamas to dive with three of the world’s most spectacular sharks: the magnificent oceanic whitetip, the awe-inspiring great hammerhead and the majestic tiger. But which encounters does he regard as 2D, and which 3D?

It seems almost unbelievable that as recently as the mid-1960s, the oceanic whitetip shark (Carcharhinus longimanus) was widely considered to be one of the world’s most abundant large animals.

Also read: Why hammerhead sharks dive on breath-hold

Nowadays these sharks are on the IUCN Red List as Critically Endangered. This is in large part because a diminutive, but incredibly resilient, former general seized control of the Middle Kingdom and unleashed economic reforms that lifted hundreds of millions of people out of abject poverty.

In the process a burgeoning middle class was created, looking for ways to show off its new wealth – one of which is the thick, fibrous and expensive concoction called shark-fin soup.

While there is much to admire about Deng Xiaoping and the incredible economic growth he enabled, the darker side of releasing the Chinese entrepreneurial genie from its bottle was rampant corruption and terrible pollution. Less obvious has beens the appalling impact that the conspicuous consumption of the Chinese middle class continues to have on the world’s oceans.

While we hear about the shark-fin trade and periodically see the hideous images of row on row of fins drying on the roofs of Hong Kong warehouses, as divers we know first-hand the impact – we have been seeing fewer sharks under water…

Roaming free

In so many ways, the oceanic whitetip personifies this hidden impact. An open-water pelagic near the top of the marine food-chain, it has evolved superbly to wander the upper water column of the world’s oceans.

Found in all tropical and sub-tropical waters across the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans but rarely seen in coastal waters, oceanics roamed free in their never-ending search for food and, with few predators and limited industrial-scale fishing, the bounty of the oceans allowed them to become a populous species.

But as the market for shark fin expanded almost exponentially in China, so did the demand for large, open-ocean fish such as tuna, mackerel, mahi mahi and swordfish, leading to the development of the deadly fishing methodology referred to as long-lining.

Despite the innocuous-sounding name, long-lining is designed to catch those apex open-ocean fish and does so with devastating efficiency, using a thick main line that is laid out and suspended from buoys every 100m or so.

Connected to these main lines are many shorter lines with baited hooks attached. A single long-line can be up to 50km long and carry more than 12,000 baited hooks!

While the ethics of long-line fishing can be debated, with proponents arguing that it is simply meeting a demand for a highly prized fish, what cannot be defended is its devastating by-catch – those cratures caught by accident.

Oceanic whitetips as bycatch

Oceanics spend the vast majority of their time roaming in what scientists call the “surface mixed layer” of the water column, which means from the surface down to about 150m.

In their domain they are the apex predator, travelling slowly but efficiently over great distances with their large, almost-winglike pectoral fins – longimanus translates as “long hands”. In that mixed layer are the tuna, barracuda, swordfish and white marlin that are oceanics’ principal source of food. It is also where the long-lining fishing-boats concentrate much of their effort.

Because they are such opportunistic feeders, oceanics are drawn onto the line of death in astonishing numbers, with clear indications that this has caused population declines of 70–80% or more in all three ocean basins.

Oceanic whitetips might not be specifically targeted by the long-liners but they provide a lucrative sideline, with those big, distinctive fins highly prized in the international fin trade.

Size matters to the status-conscious Chinese consumer, and the fact that the key ingredient in the trophy soup served at banquets and weddings comes from an apex predator carries a special cachet.

The worst aspect of oceanic shark bycatch, however, is that because their meat is considered of low value, the sharks are usually separated from their prized appendages before being thrown back into the water to drown!

This hideous practice has gone on for many years, and while there are signs it is now changing in regulated areas such as the US North-west Atlantic, there is little doubt that it continues unabated in less-controlled areas.

Hope springs eternal

When WildAid began its campaign against this practice in 2006, its research showed that 75% of Chinese people surveyed were unaware that shark-fin soup involved sharks. That’s because the Mandarin translation is “fish wing soup”. Furthermore, about 19% of those surveyed believed that the fins grew back again!

Celebrity-backed campaigns in recent years have had a big impact in China, to the point at which eating shark-fin soup became almost shameful for many younger middle-class people. However, in a country of 1.4 billion people and a middle-class of more than 700 million, there is a long way to go.

More significantly, perhaps, has been the way in which the Chinese government has got behind certain aspects of conservation, including the shark fin campaign. Whether that is because it cares or regards it as good PR is difficult to know.

But shark-fin speciality restaurants have been closed in major cities such as Shanghai and Beijing, and consuming the soup has been outlawed at official banquets.

Studies of the global shark-fin trade indicate that the market is declining, so while much remains to do, perhaps the lowest point may be behind us.

Underwater encounters

At one time the Red Sea was considered as the best place to see and photograph oceanic whitetip sharks – typically in remote locations such as the Brother Islands and Elphinstone in Egypt, or the isolated reefs of southern Sudan.

Significantly, however, these sightings are generally of lone individuals or very small groups, and little is known about the overall population of oceanics in the Red Sea, or their migration patterns.

Oceanic whitetips are formidable animals that can reach almost 4m in length when mature, and they have a reputation to match their size. Jacques Cousteau once described them as “the most dangerous of all sharks“.

When encountered under water they have an intimidating presence and are very inquisitive, seeming to have no fear whatsoever – a combination that can come over as naked aggression when first experienced.

They will come in very close and even bump you – often repeatedly, which is obviously quite disconcerting to the uninitiated… but it seems that this is simply their way of checking you out.

Cat Island

Once a common sight in the deep offshore waters around the Bahamas, from around the early 1980s oceanic whitetips became increasingly rare. It was generally assumed that they had been cleared out completely by long-lining.

Although it seemed much too late for the oceanic sharks, as part of the Bahamian government’s overall conservation programme it banned long-lining in the early 1990s.

Then, around 2005, the fishers at Cat Island started to complain about sharks stealing their catches – behaviour for which oceanics are renowned – but it was another year before it became clear that something quite special was happening.

Cat Island is a long, thin island in the middle of the Bahamian archipelago, on the eastern boundary of the main limestone carbonate platform called the Great Bahama Bank.

Its eastern and southern shores sit right on the edge of that bank, and just offshore are the deep blue waters of the western Atlantic Ocean Basin and the rich Antilles Current that sweeps up the coast as it heads north.

It is a perfect location to fish for large ocean-open pelagic fish like marlin and tuna, which is why the fishermen were there – but it was also the perfect spot for oceanic whitetips to reappear again after their enforced absence.

Quite who made the discovery is not clear, because it seems that both a BBC film-crew and National Geographic photographer Brian Skerry were there at about the same time, both following up on the same lead.

The significance of the revelation was incredibly important, however, because there on the south-eastern tip of Cat Island was what appeared to be a healthy population of oceanic whitetips. This was almost the complete opposite of what was happening elsewhere in the world, where declines of 80-90% had become the norm.

It also provided the first opportunity for scientists to tag whitetips and track their movement patterns to try and understand why they were recovering – lessons that could be applied elsewhere. Serious research began in 2010, since which time many oceanics have been tagged with satellite-trackers.

Pregnant females

Several important results have come to light, starting with the fact that while the tagged sharks roamed far and wide in the Atlantic – in some cases up to 2,000km away from Cat Island – overall, they spent most of the year in the protected waters of the Bahamas.

Probably the two most-significant results were, firstly, that over time it became apparent that the overall population of oceanic whitetips at Cat Island might be as low as 300. Secondly, while many of the sharks were pregnant females, there were no indications that they gave birth at Cat Island, leaving the challenge of finding the birthing grounds to establish a full cycle of protection.

There were indications that the north coast of Cuba might hold the secret, because government scientists there had reported significant numbers of juvenile oceanic whitetips off the small village of Cojimar.

The Bahamas has firmly established itself as a shark-diving hotspot, largely because of the tiger and lemon shark encounters at Tiger Beach on Grand Bahama, and those with the great hammerheads at Bimini.

Those encounters are what I would describe as a two-dimensional experience, where you are typically kneeling on a sandy area in shallow water and the sharks usually approach you from the front. They are reasonably predictable experiences, and it is relatively easy for support divers literally to watch your back.

Cat Island, however, offers very much a three-dimensional experience, because you are in blue water and your only point of reference is the whitebait crate suspended at about 10m.

The oceanics are attracted by the bait but are not actually fed. The mere scent seems to be enough to keep them engaged – and engaged they truly are, exhibiting no apparent fear and approaching extremely close – often to the point of bumping your domeport!

They also sneak up from behind, above and below, often coming so close that they touch you with those long fins. As exciting as all that is, I have never felt in any real danger, because it all seems part of the sharks’ pattern of testing to see whether you are the weakest link and worthy of further investigation.

How it works

Options to dive with the oceanic whitetips at Cat Island are somewhat limited because the season is short, from the end of March to mid-June, and the island lacks much of the tourism infrastructure of more popular Bahamas locations.

I booked my trip with Andy Murch of Big Fish Expeditions and he worked with Epic Diving, which is based with its boat Thresher at Cat Island during the oceanic season. Run by husband-and-wife team Vincent & Debra Canabal, Epic’s story is worth telling, because both put their professional careers on hold to pursue their passion for sharks, shark diving and shark conservation.

In Vinnie’s case, that career was as an emergency-room doctor in New Jersey, something he still does in the off-season, while Debra, a biomedical scientist, worked as an animal nutritionist.

The Bahamas was one of the first countries to understand the importance of sharks to its seas and fish stocks, and interest in shark tourism has demonstrated that live animals are far more valuable than the dead and de-finned variety!

The establishment of the Bahamas National Trust in 1959 to manage the world’s first marine protected area – the 45,600-hectare Exuma Cays Land & Sea Park – can now be viewed as an incredible piece of foresight.

The Bahamas has since added another 26 national parks, covering more than 404,700 hectares of land and sea. In 2011 the government went one step further and became the fourth country in the world to establish a shark sanctuary, by formally protecting all sharks in Bahamian waters.

It seems clear that the reappearance of a small, but healthy population of oceanic whitetips at Cat Island would never have happened if the government had not taken those measures. Nature can produce astonishing things if we humans can only give it the chance to do so.

Great hammerhead sharks

Like fashion models up on the catwalk, great hammerheads sashay into your field of vision and, if they were human, you would probably say they have just “made an entrance”.

That strange mallet-like head, robust body girth and tall sickle-shaped dorsal fin makes these sharks instantly recognisable, and most other sharks in the area spot that too, and give them a wide berth.

Great hammerheads have a unique and distinguished presence in the water, cautious but confident and seemingly in control of the environment. As they approach, their distinctive head sweeps from side to side, causing the rest of their body to move in an almost snake-like manner.

My first close encounter with a great hammerhead shark was in the Solomon Islands. Although it was fleeting, it left me thinking of how a mate of mine used to walk into the pub back in England – dressed in his best suit, cigar in hand and scanning the room in search of a date for the evening!

But like all sharks, these magnificent animals have been affected dramatically by that instaiable demand for shark-fin soup. That large dorsal fin is highly prized in the Hong Kong markets.

So encounters with great hammerhead sharks have become rare – everywhere, that is, except in South Bimini where, come winter, a sizeable number of these elusive sharks aggregate in the island’s waters.

South Bimini: Great Hammerhead Central

The islands of North and South Bimini lie on the western edge of the Bahamas archipelago, just 53 miles east of Florida, making them very popular with well-heeled owners of big boats from America’s Sunshine State.

Bimini was a favourite haunt of writer Ernest Hemingway and it was also from there that a great deal of rum was smuggled over to Florida during Prohibition in the 1920s. But perhaps it is most renowned for its sport fishing, sometimes referred to as the “big-game fishing capital of the world“.

Less well known is that South Bimini is the location of Dr Samuel Gruber’s Shark Lab. Significant research has for decades been conducted there into the sharks and rays of this part of the Bahamas.

Doc Gruber passed away in April 2019, a few weeks before his 82 birthday, after a 50-plus year career. Both enigmatic and charismatic, he had few peers in the field of elasmobranch study and research – his inspiring story is told extremely well in Jeremy Stafford-Deitsch’s book Shark Doc, Shark Lab.

Doc Gruber in fact picked Bimini because of its large resident population of lemon sharks. They use the large, mangrove-fringed lagoon system to the east of the north island as a nursery for their young, making it almost the perfect spot for research.

Many academic papers have been produced from the extensive field research conducted by Doc Gruber and his team, but what they did not tell the world about was that just off the beach, to the west of South Bimini island, ws probably the best place in the world to see great hammerhead sharks.

The Shark Lab staff first became aware of the reliable presence of great hammerheads back in 2002, but managed to keep the news to themselves for more than 10 years. Word did eventually get out and South Bimini is now firmly established as Great Hammerhead Central.

Why South Bimini?

The Bahamas are said to take their name from Baja Mar – the Spanish term for “shallow seas” – because the archipelago of 29 main islands and roughly 700 cays that form the country reside on top of two main limestone carbonate platforms called the Bahama Banks.

Great Bahama Bank covers the southern part of the archipelago and Little Bahama Bank the northern part, with incredible channels as deep as 4km separating the two.

The small islands of North and South Bimini sit at the north-western tip of the Great Bahama Bank, isolated from the rest of the archipelago and physically closer to Miami than the nearest Bahamian city of Freeport.

Their location means that to the north, south and east is the shallow water of the Great Bahama Bank, which is typically 10-15m deep, while to the west is shallow water that slopes down to about 50m before plunging into the 2km-deep channel between Miami and Bimini, through which the rich waters of the Gulf Stream flow north towards the Atlantic.

The Gulf Stream is a profoundly important force of nature and, in many ways, can be thought of as a conveyor belt of warm, nutrient-rich water that brings life to the areas it touches.

It is rich with thriving larvae swept up as it flows up from the Gulf of Mexico. These larvae are deposited at landfalls along the way, with the islands of Bimini being the first major waypoint.

Bimini is uniquely placed to benefit from that life-flow, because these are the only islands in the area big enough to sustain significant areas of mangroves and seagrass. These in turn provide the nursery those larvae need to grow into the crabs, lobster and conch that provide a food-source for the animals higher in the marine trophic food chain such as sting rays and sharks.

Bimini can be thought of as a rich, self-contained, ecosystem that has benefited greatly from the protection the government has afforded it over the years.

Face to face

Any encounter with a large animal under water brings an incredible mixture of fear and excitement that is at its most intense just before entering the water for the first time.

Sure, you have read about the animal from those divers that went before you, and the pre-dive briefings are almost always excellent. But when push comes to shove and it’s time to get in the water, I can tell you that this heart of mine is beating at an increased tempo. You could say I am focused…

Hammerheads are known to be aggressive hunters that feed on smaller fish, octopus, squid, and crustaceans, but they are not known to attack humans unless they are provoked.

In Bimini they are tempted in close by feeding, and the whole experience is carefully organised to give the participants maximum exposure to the animals. This is done by limiting the number of people in the water at any time to six, with one “feede”’ and a safety diver watching their backs.

The feeder is in the middle with an aluminium baitbox (to keep the sharks from getting over-excited) and ther three participants on either side rotate positions after 15 minutes, so everybody gets a turn next to the baitbox, where it can get very exciting!

There are usually 12 people on a trip, so after 45 minutes you get a tap on the shoulder as the time comes to give up your place and return to the boat. The safety diver is there not because of the hammerheads that often roam around behind you, but because of the bull sharks that are also quite common in Bimini. These pose the only possible danger.

All this goes on in about 12m of water, so air consumption is minimal and deco not really an issue, so the show goes on all day. Interestingly, however, the first hammerheads show up only at about 10 in the morning, so it’s a leisurely start every day.

Feeding time

The job of distributing the pieces of fish on any shark feed is clearly something of a high-risk endeavour, but with the great hammerheads it takes on quite another dimension.

As the shark approaches the feeder it can see the offered bait and, at the last minute, the feeder flicks the bait slightly to the left or the right so that the participant at that side will get a very personal photo-opportunity.

The shark sees where the bait goes and turns, but at that point the bait usually disappears under its mallet-shaped head, so it instinctively chomps away till it bites on the bait.

The issue is then that if you are next to the bait-box, the shark is chomping away right in front or on top of you – at which point you are sincerely grateful that your camera-housing is made of aluminium!

Nine times out of 10 the feeder flicks the bait upwards and the shark gets it with the first chomp, but things can get a bit hectic around the bait-box and, when they do, you really do know that it was the right decision to bring that big DSLR.

During the day it is very easy to become lulled into a sense of security as the hammerheads appear out of the distant blue, sashay in towards the baitbox where they take the proffered bait before exiting to the left or right.

After the first day or so the initial excitement has dissipated somewhat. Then you do the night dive!

After Dark

On one day we kept up the rotations until late afternoon and then, after a break and change of tanks, all 12 participants entered the water together for the dusk/night dives. This time there were two feeders, but we followed the same routine of rotating positions so that everybody got a turn next to the bait-box.

There were two very noticeable differences from the daytime “petting zoo” to which we had all become accustomed. Firstly, the hammerheads were much more active and far more aggressive at night. Instead of the slow sashay along the bottom towards the bait-box, they came in quite fast, and at chest-height.

Their body language was completely different too. It was all a bit intimidating and reinforces the fact that you are interacting with wild animals and are completely in their space!

Secondly, while we had been repeatedly warned about bull sharks, I don’t think any of us had noticed any during the day. That changed completely as dusk fell. We could see them cruising the feeding zone in the distance, but coming ominously closer each time.

The feeders would bang on the bait -ox to scare them away, but within minutes they would be back doing the same thing. However, as night fell, it became harder and harder to see where the bull sharks were. Then it dawned on me that, if they were sneaking towards us from the front, there was a distinct possibility that they were doing the same behind us!

As you can probably tell, I am not a great fan of bull sharks, and consider them the most dangerous and unpredictable of all sharks. So it was a case of being quite glad when everyone had had enough and we got the signal that the feed was over, and it was time to head back under the boat.

We had been given very strict instructions that only two people at a time were to be at the surface behind the boat at any time. We were to get out of the water as quickly as possible, because of the presence of those bull sharks. When my turn came, I produced an Olympics-worthy performance to remove myself from the water in record time!

The ethics of it all

Feeding sharks as a tourist attraction is a contentious subject and there are two basic schools of thought. The nay-sayers are adamant that it induces dangerous behavioural changes in the sharks by conditioning them to approach humans for food and therefore promoting the same (potentially) dangerous behaviour that occurs when bears, lion or crocodiles are fed.

The argument goes that sharks will be unable to differentiate between an encounter where they will be fed and one where they won’t – thereby greatly increasing the risk to humans.

The counter-argument is based on both the benefits that flow to local communities from the tourism revenue, and the lack of any substantial evidence of behavioural change in sharks.

There is no real data to support either case, so we are firmly in the realm of anecdote and opinion. However, given that his life’s work had been the study of sharks, the opinion of Doc Gruber deserves to be heard. Like most things from him, it was very clear.

“The relative risks are nil, and the relative benefits are great” is how he describes it, while conceding that there is some alteration of the shark’s behaviour, but arguing that it is not significant, and normal patterns of migration are not affected.

In other words, the availability of food in South Bimini during the main great hammerhead dive-tourism season does not change the way that the sharks behave overall. They turn up at the feeding stations for a snack, but continue to do all the other things they normally do.

Neither is there any evidence of increased aggression towards humans from the feeding of the great hammerheads.

Shark ambassadors

All that said, perhaps the biggest impact from these unique inwater encounters is that virtually all the participants leave the Bahamas as confirmed shark ambassadors. That has to be a good thing, given the ridiculous and irresponsible media coverage given to sharks generally!

Sharks have an incredibly significant role to play in the ocean. Without them the dead, the dying, the diseased and the dumb of the oceans can pollute and degrade the health of those ecosystems and the genetic quality of its inhabitants. The many species of sharks are there for a reason and they have evolved superbly, in true Darwinian fashion, to execute their mission.

Remove the sharks and disruption occurs, something marine scientists refer to rather prosaically as “trophic cascades”. Think of the shark as the first in a long line of finely balanced dominos. If it is tipped over, the rest start to go down as well.

The impact of shark-finning in the Caribbean illustrates the impact of such cascades extremely well, for when the shark population declined it removed one of the natural limitations on the number of grouper in those waters.

Grouper have voracious appetites and also breed rapidly, but a healthy shark population would keep overall numbers in check and maintain that fine balance. The grouper started to consume a disproportionate number of reef fish, which meant that the naturally occurring algae was no longer being consumed as it was, and reefs started to suffer accordingly.

There is no quick fix for these events because sharks grow slowly, mate intermittently, have long gestation periods and do not mass-produce their young. But all that gets lost in the hype that sharks generate, and the only way to really put it back in perspective is to see them in their own space.

Simply stated, South Bimini is the best place to do that with the very special creature that is the great hammerhead.

Tiger sharks

Tiger Beach is firmly established as one of those global diving destinations that almost everybody has heard of, with that fame largely derived from the many published images of its most-celebrated visitor – Galeocerdo cuvier, the tiger shark.

Tigers are considered one of the “big three” most dangerous sharks and, along with the great white and bull shark, are believed to be responsible for the vast majority of unprovoked attacks on humans.

They are renowned for their inherently predatory behaviour where, much like their terrestrial namesakes, they close in on their intended prey slowly and silently before pouncing with deadly efficiency.

They are also infamous for consuming almost anything and are often referred to as the “garbage cans of the sea“ after inspection of dead tiger shark stomach contents have revealed everything from sheep, goats and even horses to bottles, tyres, licence-plates and (believe it or not) explosives!

Tiger sharks are among the ocean’s largest sharks and typically grow to 3-5m long and weigh in at 350-700kg.

They are formidable creatures with an intimidating reputation – so how can it be that, week after week in the season, dozens of divers enter the waters of Tiger Beach for open-water, eyeball-to-eyeball encounters?

Tiger Beach isn’t a beach

Tiger Beach covers about 260 hectares on the western edge of Little Bahama Bank, about 30km west of the town of West End on the north Bahamian island of Grand Bahama.

And the first thing you need to know about Tiger Beach is that, despite the name. it is actually a shallow sandbank that looks as if there might be a beach nearby.

The area used to be known locally as Dry Bank and was first dived by Captain Scott Smith, of the Dolphin Dream liveaboard, back in the late 1980s. but who actually started the whole shark-diving thing is the subject of great discussion!

Scott Smith would seem to be the person who started tempting sharks to the stern on those early trips and the first published tiger shark images were apparently captured from of Dolphin Dream, while Jim Abernethy, owner of the Shearwater liveaboard, seems to have been the one who first took bait-boxes into the water in late 2003.

Jim is generally credited with starting the process of tempting tiger sharks to the bait boxes, and it was he who renamed the area Tiger Beach.

Whoever did what does not really matter now, but what does is that we, as divers and underwater photographers, owe a significant debt of gratitude to Scott Smith and Jim Abernathy for creating what has become the premiere location in the world for tiger shark encounters.

Understanding Tiger Beach

Satellite-tagging of tiger sharks in Bermuda has revealed two interesting facets of their behaviour – firstly, that they spend a lot of time at the surface, believed to be related to feeding and hunting patterns.

Secondly, their migration patterns are very consistent, with five to six months of the northern spring and summer months spent in the open Atlantic Ocean to the north and west of Bermuda, followed by a migration south to the Bahamas to pass the autumn and winter months.

It is believed that the months in the open ocean are related to mating and feeding on the migratory loggerhead turtles that pass through at that time of year, while the time spent in the Bahamas is related to gestation. Most of the tigers observed at Tiger Beach are females and many of them are pregnant.

Clearly, if the Tiger Beach area is the “tiger shark nursery“ it appears to be, it is incredibly important to the long-term conservation of these animals, currently on the IUCN Red List as Near Threatened, with a declining population globally.

Eye of the Tiger

Arriving for the first time at Tiger Beach is a soul-searching experience. It’s one thing to read and hear about the sharks that congregate there, but another to be there preparing for one of your first dives. Particularly when there are up to a dozen 2-3m sharks circling the back of the boat, and lots of others visible in the clear waters!

The briefings provided on these trips are both extensive and exemplary, with everything clearly explained in a logical and non-sensational way, from how to prepare and to enter the water to how to behave once submerged.

But the fact is that waiting for a gap in the patrolling sharks and then carefully rolling in among them is not the sort of thing most of us do on a daily basis.

Once under water, nerves settle and an awareness starts to form of the sharks and their behaviour patterns. From the pushy way the Caribbean reef sharks approach and tend to work in packs, to the sneaky way the large lemon sharks come in low to the bottom with a leery look, straight out of one of those horror movies.

But that new awareness fades to grey when the first tiger shark arrives. Tigers have an incredibly commanding presence; they know their place at the top of the food-chain. They move slowly and carefully, checking out what is going on, and the other sharks clearly defer to them.

The protocol at Tiger Beach is not to even worry about the lemons and reef sharks, because the only real chance of being bitten is if you break the cardinal rule of getting too close to the bait-box. Even then, a bite is unlikely to be life-threatening, but you should always know where the tigers are, and you should always face them – literally keeping the eye of the tiger in view at all times.

Tiger sharks are intelligent and inquisitive animals that tend to approach divers because their sensory systems pick up the tiny electrical and audible signals emitted from our instrumentation and photographic equipment.

They will tend to bump with their snouts as they investigate the stimuli further, and there is always the chance that will use their mouth and, because their jaws are so powerful, even a gentle nip could be life-threatening.

So photographers are instructed to use their cameras as a shield, with the strict instruction to let go if a tiger decides to do a taste test – but do remember to press the video button…

Petting zoo…

Being in the open water with so many large and potentially dangerous sharks verges on a life-changing experience. It really is a big deal to be there and the first few days are a kaleidoscope of feelings – fear, awe, intimidation, excitement and an incredible sense of adventure at what you have done.

Then a degree of complacency starts to settle in as you begin to think that perhaps these animals have simply been misunderstood all along, and tare really just kind and gentle creatures…

This for me is when Tiger Beach does become dangerous, because you are in a very special place where these creatures are both protected and well-fed naturally, as well as getting the snacks from the bait-box. So you are not really seeing them in their natural environment and, in a way yes, it is a kind of petting zoo.

…or real deal?

Tiger Beach is unique; there really is nowhere quite like it. Where you can be in the open water in relative safety with so many large and potentially dangerous sharks?

The relative safety comes from the fact that the sharks at Tiger Beach have become accustomed to the presence of divers and, because they have plenty of other things to eat, they do not regard us as a principal food source.

It is absolutely not a completely natural setting, but there is little else like it if you want to see these creatures so close up. It is the real deal!

Photographs by Don Silcock

Also on Divernet: Exploring The Best Of The Bahamas, Shark ‘Eyes’ Reveal Biggest Blue CO2 Trap, Tiger Sharks Range Far But Don’t Mix, Why Great Hammerheads Like To Swim Tilted, Oceanic Whitetips On The Brink